CONTENTS

To my father and mother for the past,

to Natalie and Isabelle for the future,

and to Woody for the here and now.

Note to the Reader

The narratives in this book are true. A few of the subjectsErika, Celia, Susan, Hasan, Dorinne, and my family membershave permitted me to use their real names. In all the other narratives, I have changed the names and the identifying details in order to maintain confidentiality.

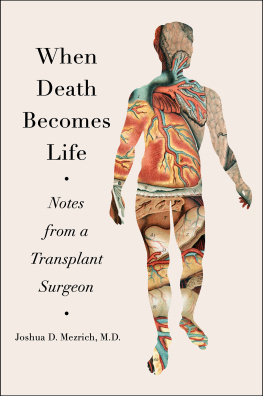

INTRODUCTION

Erikas voice on the other end of the line has the same soprano clarity I remember from college. It has been nearly twenty yearsand between us, two completed residencies, two weddings, and four childrensince our last conversation, but my college roommate and I are talking again, helped in part by the breezy missives of the Internet. Earlier that afternoon I received an e-mail from Erika briefly telling me that her father, Dr. Schillinger, a clinical psychologist, had just died. Its made me want to reconnect with the past, she wrote.

I remember Erikas father. One afternoon when her parents were visiting, Erika put a Tommy Dorsey record on our feeble dorm room sound system. I watched Dr. Schillinger in his navy cardigan and low-perched reading glasses rise from our red vinyl couch, grab Erikas right hand, and twirl her to the music. His Hitchcockesque silhouette became weightless, and he danced in a way that I believed impossible for someones parent.

On the phone Erika tells me that last year her father was diagnosed with metastatic gastric cancer. He tried a few rounds of chemotherapy but developed pulmonary fibrosis, a stiffening of the lungs that slowly suffocates. Bed-bound and weakened by the slightest exertion, Dr. Schillinger persisted in crooning to Erikas eight-month-old daughter, making her shimmy as he sang. By the end of each line the alarm on his blood oxygenation monitor would cry out, but Dr. Schillinger, ignoring the electronic warnings and Erikas pleas to stop, would warble on.

When the struggle to breathe finally became unbearable, Dr. Schillinger signaled to his daughter: he wanted only to be comfortable. Despite his terminal diagnosis, Dr. Schillingers doctors had made no provisions for this moment. Instead, in his last hours Dr. Schillinger had to look to Erika, his physician daughter, for guidance. None of his doctors was even present, and it was Erika who had to ask for morphine, knowing that the drug would both alleviate her fathers suffering and suppress his drive to breathe.

Talking to me a month after, Erika weeps, remembering the responsibility of the moment. Do you know how many times death was mentioned during those last few months? she asks me. I cannot begin to guess; anyone with some medical training could have seen that Dr. Schillinger was a terminal patient.

Once, she says, that crystalline voice faltering. A doctor discussed dying once with us. Otherwise, all anyone ever talked about was treating my father. Erika pauses and then asks me, Why are we so bad at taking care of the dying?

Twenty years ago when I was applying to medical school, I believed I was going to save lives. Like the heroic doctors of my imagination, I would spend my days in triumphant face-offs with death and watch the parade of saved patients return to my office full of life, smiles, and back-slapping gratitude. What I did not count on was how much death would be a part of my work.

In a profession made attractive by the power to cure, it is rare to find the young medical student who dreams of caring for terminal patients. But in a society where more than 90 percent fully expect physicians to be able to comfort and provide that support. For doctors, this care at the end of life is, as this books title implies, our final exam.

Unfortunately, few doctors are up to the task.

Like most of my colleagues, I came into medicine poorly equipped to deal with terminal patients. I had little experience with the dying beforehand and like many physicians harbored a profound aversion to death. However, during almost fifteen years of school and training, I faced death over and over again. And I learned from many of my teachers and colleagues to suspend or suppress any shared human feelings for my dying patients, as if doing so would make me a better doctor. These lessons in denial and depersonalization began as early as my first encounter with death in the gross anatomy dissection lab and were reinforced during the chaos of residency training and practice.

As I learned and eventually even mimicked these coping mechanisms, I found myself wrestling with disturbing inconsistencies that only multiplied over time. There was a dying friend I could not call, a young patients tortured death that I could not forget, and even the sense of shared humanity with a corpse that I could not cast aside when I was asked to saw her pelvis in two. These small but powerful moments, magnified every time I encountered death, would finally give me insight into how my own fears and trained responses had, in the end, incapacitated me. In acknowledging the painful consequences and paradoxes of my behavior, I began to extricate myself from those learned responses. Amid the pain of losing patients, I learned that I might be able to do something greater than cure. I could provide comfort to my patients and their families and in turn open myself to receive some of their greatest lessons.

Final Exam: A Surgeons Reflections on Mortality is a compilation of my experiences dealing with death. It weaves personal narratives from fifteen years of clinical experience with reflections on some of the broader issues in medical education and end-of-life care. The first section, Principles, focuses on the earliest lessons in medical school regarding deaththe cadaver dissection, the first resuscitation, the first pronouncement of death. These earliest experiences pit the neophyte medical student and intern against some of the most difficultsome would call them terrifyingexperiences in clinical medicine, often without the benefit of much psychological or emotional preparation. The lessons young doctors draw from these experiences then become the foundations of their future practices.

The second section, Practice, delves into the heart of clinical work, revealing how our professional responses not only manifest but also perpetuate themselves. There is an essential paradox in medicine: a profession premised on caring for the ill also systematically depersonalizes dying. However, when viewed from within the daily rhythms of clinical work, there is an internally coherent logic. What seems inhumane or cruelevading difficult patient conversations, ramping up treatment in terminal diseasescan be entirely rational to the foot soldiers in the clinical trenches. And that logic makes change, at least for the practicing resident, seem nearly impossible.

The final section, Reappraisal, explores how change is in fact possible. From the microcosm of a single doctors practice to the medical profession as a whole, there have been small but hopeful transformations in how doctors approach end-of-life care. And these changes have been the result of more than just critical appraisals of our professional training and institutions; they have required recognizing our own mortality and a shared humanity with our patients.

Whether we are physicians or not, facing that mortality in ourselves is perhaps the most difficult task of all. As Freud wrote, [I]n the unconscious every one of us. Freud went on to say:

Next page