DEAD MEN RISEN

DEAD MEN RISEN

THE WELSH GUARDS AND THE REAL STORY OF BRITAINS WAR IN AFGHANISTAN

TOBY HARNDEN

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Quercus

21 Bloomsbury Square

London

WC1A 2NS

Copyright 2011 Toby Harnden

The moral right of Toby Harnden to be

identified as the author of this work has been

asserted in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication

may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any

information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

Lines from Home front from the collection Laurels and Donkeys (Clutag

Press, 2010) are reprinted by kind permission of Andrew Motion.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders of material

reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the

publishers will be pleased to make restitution at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

HB ISBN 978 1 84916 805 2

HB ISBN 978 1 84916 421 4

TPB ISBN 978 1 84916 422 1

Text designed and typeset by Ed Pickford

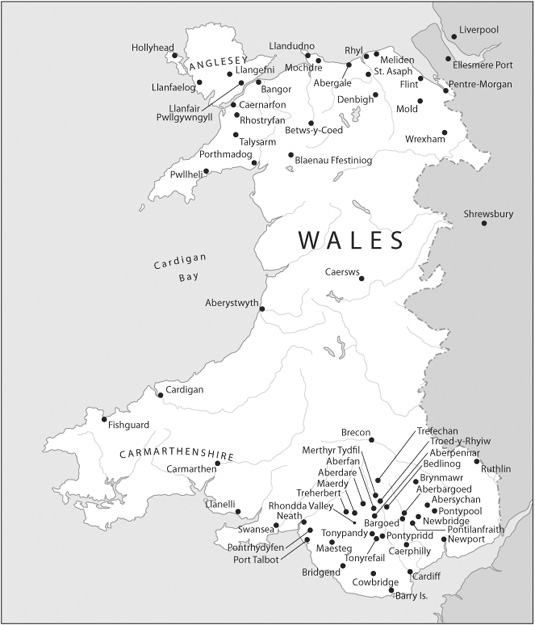

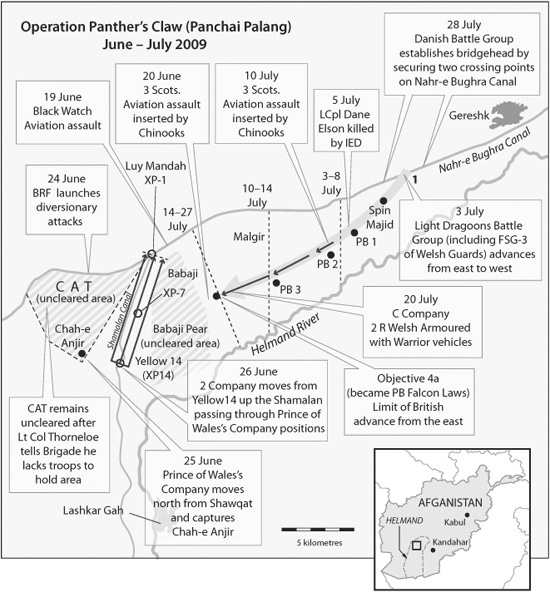

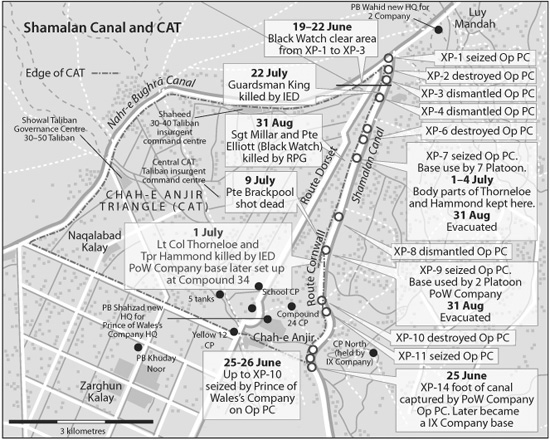

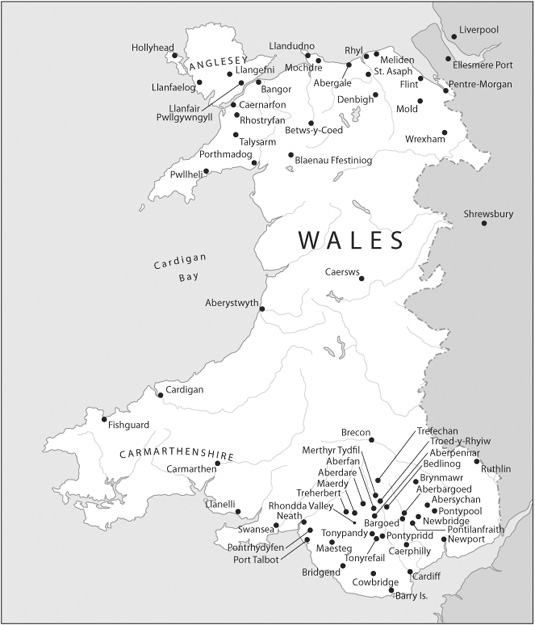

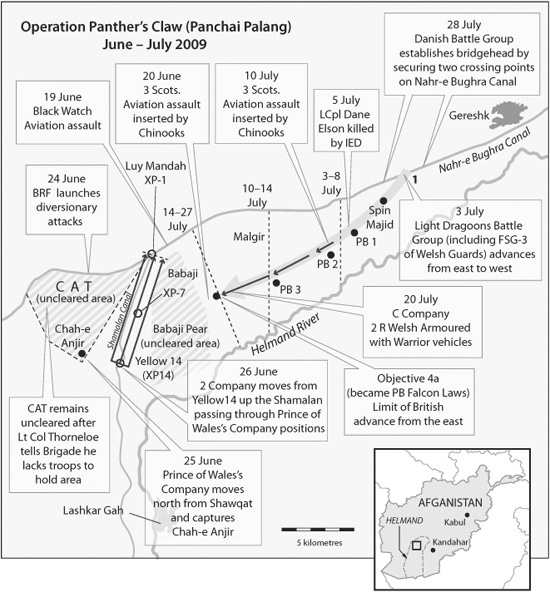

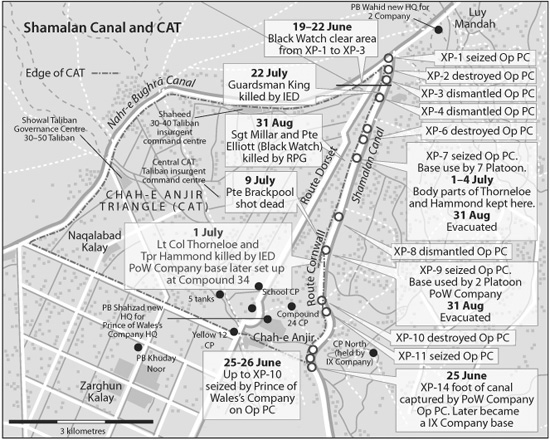

Maps William Donohoe

You can find this and many other great books at:

www.quercusbooks.co.uk

In memory of the Welsh Guardsmen and their comrades who did not return.

For Cheryl, Tessa and Miles Harnden

Authors Note

This book is about what it was like to fight as a Welsh Guardsman in Helmand in 2009. The account will bear little resemblance to what you will have read in the newspapers, heard politicians describe, or tried to glean from the upbeat progress reports of generals. War is chaotic and gruesome as well as, on occasions, noble and heroic. The reader is not spared that reality.

In his history of the Irish Guards from 1914 to 1918, Rudyard Kipling wrote of the difficulties of retrieving sure facts from the whirlpool of war. Some things that at first looked straightforward when I was on the ground in Helmand with the Welsh Guards now appear much more complicated. Areas of near-conviction in my mind then are now shrouded in uncertainty.

Kiplings two-volume work included the death of his only son John, a lieutenant who perished in September 1915 at Loos, the first battle in which the Welsh Guards fought. Men grow doubtful or oversure, and, in all good faith, give directly opposed versions, he wrote. Sifting through the personal prejudices and misunderstandings of men under heavy strain, carrying clouded memories of orders half given or half heard, amid scenes that pass like nightmares was, he found, a task replete with pitfalls. The more he learned, the more difficult it became to establish what really happened because the end of laborious enquiry is too often the opening of fresh confusion.

This has been my experience over the course of nearly 18 months spent researching Dead Men Risen. During that time I conducted some 246 hours of audio-recorded interviews with more than 260 people, predominantly in Afghanistan, Wales and England. Many were interviewed several times. A number of further interviews were done on a background basis with no recording. I examined 2,374 military documents made available to me and drew on other sources including letters, diaries, emails, videos, Royal Military Police reports and the proceedings of coroners inquests. Acknowledgements of those who have assisted me appear after the main text.

As part of the required publishing agreement with the Ministry of Defence (MoD), the manuscript was submitted for review by the Army. This resulted in 493 separate questions, suggestions or requests for changes to be made, followed by protracted discussions that continued even after printing.

The narrator of Robert Louis Stevensons Treasure Island sought to present the whole particulars of what happened from the beginning to the end, keeping nothing back but the bearings of the island. In this case, the bearings of the island are those matters that could endanger the operational security of British troops. To protect the safety of those in Afghanistan and for legal reasons a number of redactions have been made at the MoDs request and appear as blacked-out passages. For reasons of personal security or privacy or at their own request, a number of people are identified only by a pseudonym. These appear as: Guardsman Ed Carew, Corporal Chris Fitzgerald, Private Wayne Gorrod, Lieutenant Piers Lowry, Trooper Jeremy Murray, Rifleman Mark Osmond, Serjeant Tom Potter, Captain Richard Sheehan and Guardsman Gavin Wynne.

Dead Men Risen should be read with close reference to the maps at the start of the book and the plans of incidents that appear alongside the text. Appendices outline the structure of the Battle Group, highlight the principal figures and list every Welsh Guardsman who served in Afghanistan in 2009 as well as many others who were attached to the Battle Group.

At the head of that list is the name of Lieutenant Colonel Rupert Thorneloe, who became a friend in Northern Ireland in the late 1990s, when I was a journalist and he was a military intelligence officer. After I first visited Helmand at the start of 2006, before British troops had begun to arrive, I stopped in Kabul on my way home. I went to the bleak, snow-covered British Cemetery, where crumbling tombstones recalled the men who had fought for Queen and Empire in Afghanistan only to be, in the words of Kipling, left on Afghanistans plains to go to their Gawd like a soldier. Days earlier in Helmand, an American development official had predicted to me that British troops would get hit on the roads while an Afghan warlord told me that some still sought vengeance for the wars of the nineteenth century. Soon, I reflected in print, there would be new memorials for those from another generation of courageous Britons who would be cut down by the Pashtuns. When I went to the cemetery again in early 2010, Rupert Thorneloes name had just been carved on a marble tablet. By the end of that year, a total of 348 British troops had been killed in Afghanistan since 2002.

Nothing in these pages is intended to pass judgement on any of those who fought in Helmand. War is messy and frightening. Rare is the soldier throughout history who ever possessed all the information needed to make the right decision, the optimum plan or all the equipment desired to carry out that plan. For most troops in Helmand, facing each new day required an act of bravery to function despite the knowledge that it might well be their last. They gave their all and did what they thought was right. When they returned, their loved ones welcomed back a different person.

This is a story of the Welsh Guards, of the British Army and of Afghanistan. It is both a privilege and a responsibility to be able to tell it.

Prologue

Next page