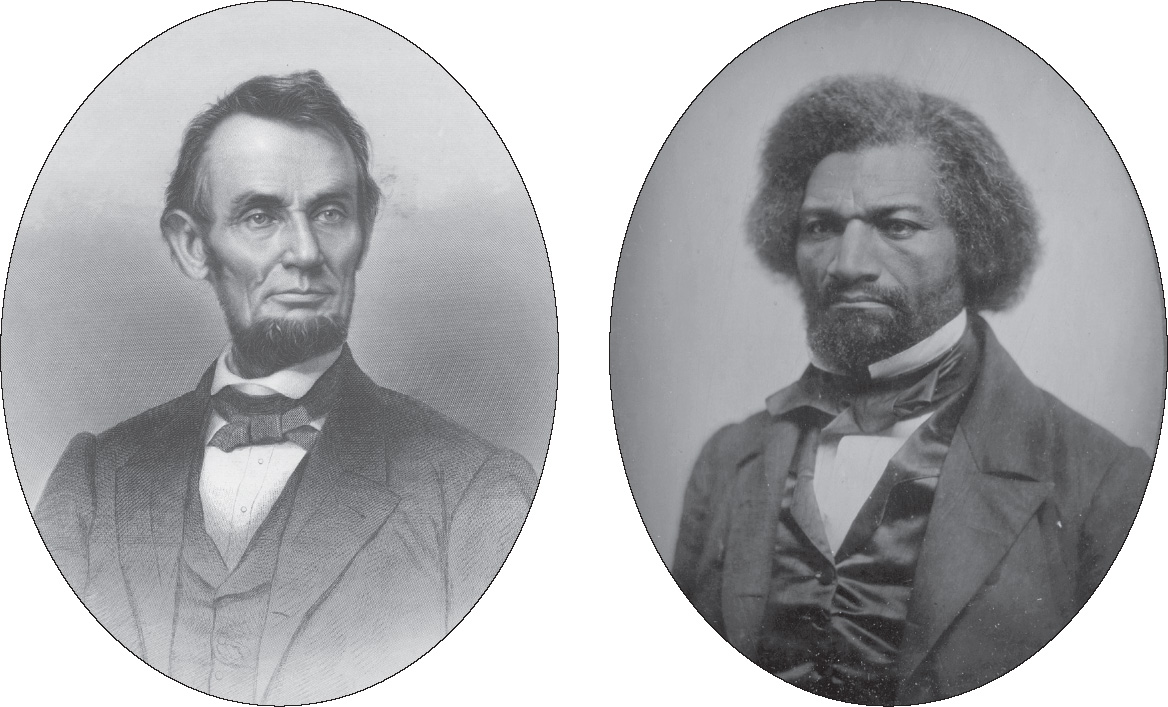

Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.

Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.Clarion Books

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003

Copyright 2012 by Russell Freedman

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Clarion Books is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

www.hmhbooks.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Freedman, Russell.

Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass : the story behind an American friendship / by Russell Freedman.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-547-38562-4

1. Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Juvenile literature. 2. Douglass, Frederick, 18181895Juvenile literature. 3. PresidentsUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. 4. African American abolitionistsBiographyJuvenile literature. 5. FriendshipUnited StatesJuvenile literature. I. Title.

E457.905.F725 2012

973.7092'2dc23

2011025953

eISBN 978-0-547-82286-0

v2.0812

To Dick Mayer

for the gift of friendship

Introduction

When I was growing up in San Francisco during the Second World War, I would ride my bicycle down to the beach, walk across the sand, and stand at the waters edge, looking out at the crashing waves and the wide Pacific. In my minds eye I could see exactly where I was standing on a map of the world. Over my shoulder to my right, that was north and Canada; to my left, south and Mexico; and straight ahead, far to the west was China, which, for some odd reason, was said to be in the East. If I climbed into a boat and sailed away and kept on sailing, sooner or later I would reach that distant and mysterious place called China. The idea thrilled me, all the more so because it seemed an impossible dream.

Like so many dreams, that one was put on the shelf as I went to college, served with the 2nd Infantry Division in Korea, and found my calling as a writer of nonfiction books on subjects that interest me. Abraham Lincoln was an irresistible subject. A poor backwoods boy, he rose from a log cabin to the White House. Self-educated, he became an eloquent writer. Brooding and melancholic, he was known for his jocular sense of humor. As president, he saved the Union from dismemberment and ruin, as Frederick Douglass observed, and freed his country from the great crime of slavery. The more I learned about Lincoln, the more I came to appreciate his subtleties and complexities. The man himself turned out to be vastly more interesting than the myth.

In 1988 my biography of Lincoln was awarded the Newbery Medal. So I figured that the time had come. I celebrated by realizing my boyhood dream and traveling to China in the spring of 1989 with a friend who is fluent in Cantonese, Mandarin, and some regional dialects. Thanks to his language facility, we were able to travel around the country freely for almost three months. China had not yet become an economic superpower. It was still a nation of tile-roofed villages and low-rise cities. People in Beijing lived among the narrow lanes and alleys of traditional hutongs, and bell-ringing bicycle riders commanded every intersection.

In June of that year, we found ourselves in the midst of a massive and continuing pro-democracy demonstration taking place in Beijing. Thousands of students were camped out in Tiananmen Square in the heart of the city, where they had erected a papier-mch Goddess of Liberty, their version of the Statue of Liberty. And every day, tens of thousands of demonstrators from all walks of life were surging down Changan Avenue, the broad Avenue of Eternal Peace that leads to the square. They paraded by on foot and on bicycle, in commandeered buses and in trucks, carrying banners, waving flags, chanting slogans, and singing patriotic songs as crowds lining the avenue applauded and cheered.

I shall never forget watching as a gigantic banner, held aloft by twenty or thirty marchers, came toward me down the avenue. A huge face had been painted on that banner, and when I first saw it, I thought I must be mistaken. It was the face of Abraham Lincoln. And beneath his beard, in Chinese characters, were the words Government of the people, by the people, for the people.

A government surveillance helicopter clattered overhead, circling above the crowd. People looked up at it and jeered.

No one we spoke to in Beijing expected a violent government crackdown. But on June 4, Chinese army tanks and troops moved into Tiananmen Square, crushed the Goddess of Liberty, and cleared the area of demonstrators. The exact number of civilian deaths, estimated from the hundreds to the thousands, is unknown.

Before leaving China, we saw a half-torn wall poster, written in bold characters: ONCE UPON A TIME IN BEIJING, THERE WAS NO DEMOCRACY YET. I was reminded that Lincoln is not just a pivotal figure in the story of America, my country, but a universal symbol of freedom and democracy. He represents a vision of America that is held as a matter of faith by people all over the world.

Russell Freedman

2011

The White House, around 1865.

The White House, around 1865.One

Waiting for Mr. Lincoln

Heads turned when Frederick Douglass walked into the White House on the morning of August 10, 1863. It was still early, but the waiting area leading to Abraham Lincolns office was crowded with politicians, officials, patronage seekers, and citizens of all kinds seeking an audience with the president.

Douglass was the only black man among them. The others seemed surprised to see him, and some were none too pleased.

Lincoln tried to meet with as many callers as he possibly could each day. He said he enjoyed his public opinion baths and found them a useful way to find out what people were thinking. When first elected, he had refused to limit his visiting hours. They do not want much, he said of the throngs of citizens waiting to see him one day, and they get very little.... I know how I would feel in their place.

But the crowds became unmanageable. People showed up before breakfast and were still waiting to see him late at night. At times, even U.S. senators had to wait a week or more to speak with the president. As his work piled up, Lincoln realized that he had to restrict his visiting hours. He saw callers from ten o'clock in the morning till one in the afternoon. Priority was given to cabinet members and congressmen; if any time remained, ordinary citizens were admitted.

It wasn't easy to see the president. Not everyone got in.

Douglass handed his calling card to a clerk and looked around for an empty chair. None was available, so he found a place to sit on the stairway leading to Lincoln's office. The stairs were filled with other men hoping for a moment with the nation's chief executive.

Douglass had no appointment. He had no idea how long he might have to wait, or even if he would be granted an interview. By meeting with the president, he hoped to secure just and fair treatment for the thousands of black troops who had enlisted in the Union army and were now fighting for the North in America's Civil War.

When the war began, federal law prohibited blacks from serving in the army. But as the fighting continued, with mounting casualties and no decisive victories, the North finally allowed African Americans to enlist. Black soldiers fought with distinction, but they were paid only half as much as white soldiers and were not being promoted for outstanding service. Worse, black prisoners of war were being executed or enslaved by their Southern captors.