The book is also dedicated to the memory of my husband, Matthew Carr. He was always the first person to be shown the typescript of my books and although he died before he could read it all, he delighted me with his enthusiasm for the sections he did see. It is one of many ways in which he is greatly missed.

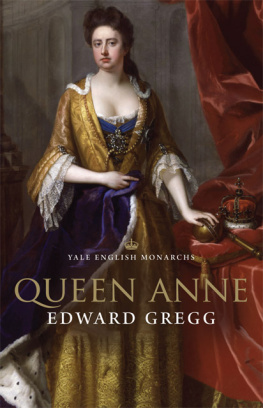

James II, when Duke of York, with Anne Hyde and their two daughters, Princess Mary and Princess Anne c. 167480. By Sir Peter Lely and Benedetto Gennari. (The Royal Collection 2011)

The Lady Anne as a child. Artist Unknown. (Royal Collection 2011)

Queen Anne when Princess of Denmark. By Willem Wissing and Jan van der Vaardt. ( Scottish National Portrait Gallery)

Sarah Churchill (later the Duchess of Marlborough) with Lady Fitzharding, 1691. By Sir Godfrey Kneller. ( Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire, UK/The Bridgeman Art Library)

Prince George of Denmark on horseback, 1704. By Michael Dahl. (Royal Collection 2011)

Princess Anne of Denmark with the Duke of Gloucester, c. 1694. After Kneller ( The National Portrait Gallery, London)

Queen Mary II. After Willem Wissing. ( The National Portrait Gallery, London)

William, the Duke of Gloucester, with his friend, Benjamin Bathurst. After Thomas Murray The National Portrait Gallery, London)

Queen Anne, 1703. By Edmund Lilly. ( Queen Anne, 1703, Lilly, Edmund (fl.1702d.1716)/Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire, UK/The Bridgeman Art Library)

Sidney Godolphin. After Sir Godfrey Kneller. ( The National Portrait Gallery, London)

The Duke of Marlborough. By Sir Godfrey Kneller. ( The National Portrait Gallery, London)

Queen Anne with Prince George of Denmark. By Charles Boit, 1706. (Royal Collection 2011)

Print of Her Majesties Royal Palace at Kensington. ( British Museum)

Tapestry showing the French Marshal Tallard surrendering his baton to the Duke of Marlborough after the Battle of Blenheim in August 1704. (Image reproduced by kind permission of His Grace the Duke of Marlborough, Blenheim Palace Image Library)

Robert Harley Earl of Oxford. By Jonathan Richardson. ( Private Collection/Photo Philip Mould Ltd, London/The Bridgeman Art Library)

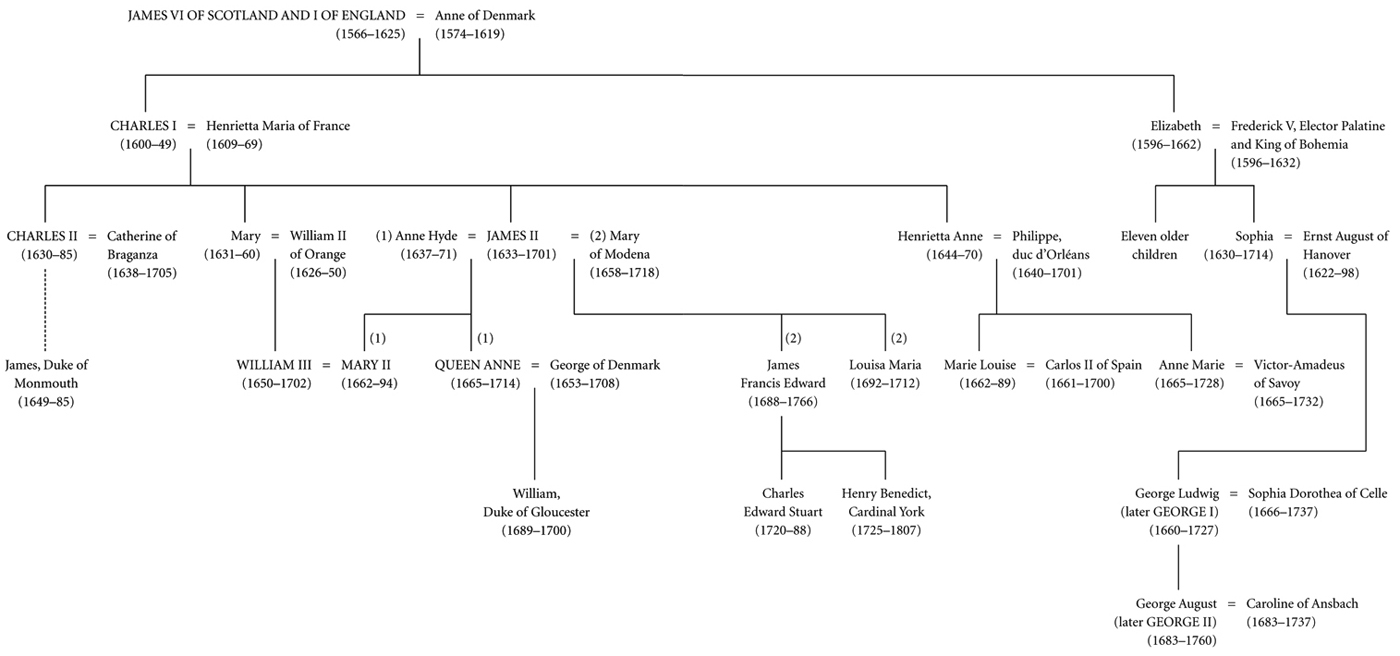

Sophia Electress of Hanover. (Royal Collection 2011)

Portrait believed to be of Abigail Masham. ( Philip Mould Ltd London/The Bridgeman Art Library)

Henry St John, Viscount Bolingbroke. By George White, after Thomas Murray. ( The National Portrait Gallery, London)

Prince James Francis Edward Stuart (the Pretender). Studio of Alexis Simon Belle. ( The National Portrait Gallery, London)

Anne in the House of Lords. By Peter Tillemanns. (Royal Collection 2011)

The Battle of Malplaquet, 11 September 1709, c. 1713. By Louise Laguerre. ( National Army Museum, London/The Bridgeman Art Library)

Satirical print of Bolingbroke dictating business relating to the Treaty of Utrecht. ( British Museum)

Queen Anne and the Knights of the Garter. By Peter Angelis. ( The National Portrait Gallery)

For the sake of clarity I have updated spelling and punctuation used in original documents. Furthermore, in almost all cases when Anne or her contemporaries used the abbreviations ye and yt in their letters, I have modernised the archaic usage by substituting the and that. Very often Anne and her ministers ciphered their letters by substituting numbers for names. In such cases I have omitted the numbers and replaced them with the relevant name in square brackets.

Throughout Annes lifetime, England used the Julian Calendar, while continental Europe followed the Gregorian system. During the seventeenth century, the date in Europe was ten days ahead of Englands; with the start of the eighteenth century the gap between England and Europe widened to a difference of eleven days. When dealing with events that took place in England, I give dates according to the Julian Calendar. However, when describing events that occurred on the Continent, or when quoting letters sent from abroad, I generally give a composite date, separated by a forward slash, indicating the date according to both the Julian and Gregorian calendars. Whereas in Stuart England, the calendar year started on 25 March, I have simplified things by taking it to begin on 1 January.

It is notoriously difficult to compare the value of money in the past with modern monetary values. However, as a very rough guide it should be noted that the National Archives Currency Converter Service calculates that 1 in 1710 would have a spending worth of 76.59 in 2005.

But a Daughter

The opening weeks of the year 1665 were particularly cold, and the sub-zero temperatures had discouraged the King of England, Charles II, from writing to his sister Henrietta in France. He was always a lazy correspondent, and having little news to impart thought it pointless to freeze my fingers for nothing. In early February, however, he took up his pen to report that the two of them had acquired a new niece. On 6 February, shortly before midnight at St Jamess Palace in London, their younger brother James, Duke of York, had become a father to a healthy baby girl. Being without a legitimate heir, the King would have preferred a boy, and since Henrietta herself was expecting a child, Charles told her that he trusted she would have better luck in this respect. In one way, however, the Duchess of York had been fortunate, for she had had a remarkably quick labour, having despatched her business in little more than an hour. Charles wrote that he wished Henrietta an equally speedy delivery when her time came, though he feared that her slender frame meant that she was not so advantageously made for that convenience as the far more substantially built Duchess. The King concluded that in that event, a boy will recompense two grunts more.1

The child was named Anne, after her mother, and if her birth was a disappointment, at least it did not cause the sort of furore that had greeted the appearance in the world of the Duke and Duchess of Yorks firstborn child in 1660. That baby had initially been assumed to have been born out of wedlock, but when it emerged that the infants parents had in fact secretly married just before the childs birth, there was fury that the Duke of York had matched himself with a loose woman who was not of royal blood. Many people shared the view expressed by the diarist Samuel Pepys that he that doth get a wench with child and marries her afterward, it is as if a man should shit in his hat and then clap it upon his head.2

The scandal was particularly regrettable because the monarchy was fragile. Charles II had only been on his throne since May 1660, after an eleven-year interregnum. In 1649 his father, King Charles I, had been executed. This followed his defeat in a civil war that had started in 1642 when political and religious tensions had caused a total breakdown in relations between King and Parliament. During that conflict an estimated 190,000 people nearly four percent of the population had lost their lives in England and Wales alone; in Scotland and Ireland the proportion of inhabitants who perished was still higher. Charles I had been taken prisoner in 1646, but refused to come to terms with his opponents and so the war had continued. By 1648, however, the royalists had been vanquished. Angered at the way the King had prolonged the bloodshed, the leaders of the parliamentary forces brought him to trial and sentenced him to death. England became a republic ruled by a Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, and it seemed that its monarchy had been extinguished forever.