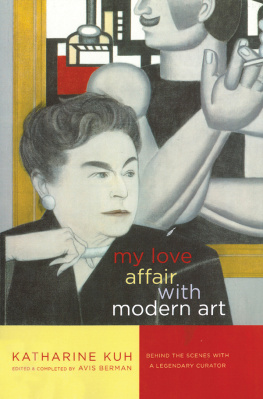

my love

affair

with

modern art

Also by Katharine Kuh

Art Has Many Faces: The Nature of Art Presented Visually Lger

The Artists Voice: Talks with Seventeen Modern Artists Break-Up: The Core of Modern Art The Open Eye: In Pursuit of Art

Also by Avis Berman

Rebels on Eighth Street:

Juliana Force and the Whitney Museum of American Art

James McNeill Whistler

Edward Hoppers New York

my love

affair

with

modern art

BEHIND THE SCENES WITH

A LEGENDARY CURATOR

KATHARINE KUH

EDITED & COMPLETED BY AVIS BERMAN

ARCADE PUBLISHING

NEW YORK

Copyright 2006, 2012 by Avis Berman

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or arcade@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-506-9

Printed in the United States of America

For all who knew Katharine and in memory of my father

Contents

Preface

Katharine Kuh was always too vehemently involved with life to let death, let alone the opinions of other people, stand in the way of her voice. When she began writing these reminiscences at the age of eighty-seven, she didnt care what the task might exact from her in physical strength or mental energy. I myself was skeptical of the enterprise. Of course, I encouraged her to persevere with the notion of a book, because from years of hearing her stories, I knew and loved the rich texture of Katharines life. As her friend and literary executor, I was eager to read and help her to publish anything she wrote, but I wasnt persuaded that she had the stamina or concentration for such sustained work. Happily, she confounded me and a number of others who knew her: the prospect of being an author again and the dedication it entailed got her up in the morning and kept her active every day. Katharines blazing determination trumped my stereotyped expectations of what was possible or prudent for someone of her age and health. When she died, on January 10, 1994, at the age of eighty-nine, she had written three-quarters of this manuscript.

Nevertheless, in the piles of handwritten notes, typescripts, clippings, envelopes, and folders that had been accumulating, Katharine also left essays in various stages of gestation. In addition to writings that had been abandoned and perhaps not destined for publication, other chapters were in a rudimentary state and lacked the analysis and brio she had brought to the polished chapters that unquestionably represented a final summation. Because I had interviewed Katharine extensively about her professional life beginning in 1982 and written about her on several occasions, she asked me to complete her memoirs if she did not live to do so. Yet my primary criterion for including material was that it had to stand as Katharines writing, expressed in the first-person point of view. If the pages in question had to be augmented so substantially by me as to render them a secondhand research article about the subject, as opposed to a personal account based on Katharines direct observation, participation, and explication, I did not retain them. If I could not fill gaps and construct transitions as I think Katharine would have, I forfeited the raw information. In my editing, I tried to proceed as a thoughtful conservator would in restoring a fine painting. I refined and polished where needed, but I did not alter the meaning or expression of the essential composition.

However, for the sake of forming a book as a whole, I did have to write extended portions of this volume. In almost all instances, I depended on Katharines letters, publications, and scrapbooks, along with my own knowledge and recollections. In addition, I had an indispensable resource a three-hundred-page transcript of an interview I conducted with Katharine throughout 1982 and 1983 for the Archives of American Arts oral history program. For that project, I was supposed to make three or four recordings of Katharines recollections, but she possessed such scope and mesmerizing recall that I ended up taping her fifteen times instead. Well before the interviewing was finished, we had become friends. Whenever I was unsure of an opinion or an attitude or if Katharine changed her mind about a certain person, event, or subject, I would search through her catalogues, magazine articles, and the oral history until I found the answers or pregnant clues I needed. As a rule, I made a point of expressing the missing thoughts or data in a manner as close to her syntax as I could manage.

While I did have ample primary documentation before me, Katharine took care to suppress several cardinal facts about her early life and career. Had she lived, it is debatable if she would have acquiesced to supplying personal information to an imploring publisher. Katharine had grown up and matured in an age that valued privacy and decorum, discretion above sensation and revelation. When she described Edward Hoppers reserve, she responded to that tight-lipped rectitude with admiration and understanding. Katharine was frank about personal matters to friends, but committing such truths to print was abhorrent to her. Reticent about her private life, she genuinely believed that her own personality was not as central as those she wrote about. As she saw it, the legacy of her writing would be judged in proportion to how directly it reflected an engagement with artists the source of the experiences that most intensely enkindled her life. She was shocked and baffled that John Canaday, who was chief art critic at the New York Times while she was at Saturday Review, advocated avoiding all personal contact with artists, lest his impartial judgments be threatened. She objected that impartial judgments could not exist in art because strong emotions and total involvement are prerequisites of understanding. For Katharine, warm familiarity with artists was invaluable in comprehending the vitals of art and transmitting that intelligence to the public. Nothing, she stated, could substitute for the experience of seeing an artists paintings, one by one, in his or her studio. She buttressed her case by arguing that when studying earlier masters, we long to have secrets unraveled that only personal accounts might have disclosed.

The value of her memoirs, Katharine maintained, lay in her history as the rare confidante of Clyfford Still, as the world traveler who led Hopper to the one place in Mexico that fused with his imagination, as the insider visiting Isamu Noguchis house in Japan, or as the eavesdropper on the priceless remark, as when she heard Walter Gropius say to Mies van der Rohe, All that work and what have we got to show for it the picture window? In other words, she felt that her writing made a contribution only insofar as it willingly remained subservient to the far more creative forces which were its raison dtre. Katharine also regarded criticism as an offshoot of her real work, which, as she defined it, was knowing about works of art, whether they were produced in the past or present. Judging them, understanding their condition, knowing how to read an X-ray photograph revealing the layers of an old painting or recognize if a drawing has been reinforced these are the things that have interested me. What she loved most, whether as writer or curator, was the act of looking and, ultimately, of seeing.