CLEOPATRA

ALSO BY JOYCE TYLDESLEY

For Adults

Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt

Hatchepsut: the Female Pharaoh

Nefertiti: Egypts Sun Queen

The Mummy

Ramesses: Egypts Greatest Pharaoh

Judgement of the Pharaoh: Crime and Punishment in Ancient Egypt

The Private Lives of the Pharaohs

Egypts Golden Empire

Pyramids: The Real Story Behind Egypts Most Ancient Monuments

Tales from Ancient Egypt

Egypt: How a Lost Civilization was Rediscovered

Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt

Egyptian Games and Sports

For children

Mummy Mysteries: The Secret World of Tutankhamun

and the Pharaohs

Egypt (Insiders)

Stories from Ancient Egypt

CLEOPATRA

LAST QUEEN OF EGYPT

JOYCE TYLDESLEY

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

New York

Copyright 2008 by Joyce Tyldesley

First published in the United States in 2008 by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

Published in Great Britain in 2008 by Profile Books Ltd

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever

without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied

in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books,

387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016-8810.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts

for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions,

and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special

Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street,

Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000

or e-mail .

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

HC ISBN: 978-0-465-00940-4

PB ISBN: 978-0-465-01892-5

LCCN: 2008921307

British ISBN: 978 1 86197 965 0

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Dedicated to the memory of my late father,

William Randolph Tyldesley

Contents

P ersonal names are a potential minefield for the student of ancient history. I have aimed at clarity for those new to the Ptolemaic age, and can only apologise in advance to those who may feel that I have made irrational, inconsistent or unscholarly decisions. Throughout the book I have favoured the traditional spelling Cleopatra rather than the more authentic but less widely known Kleopatra. Similarly, when using Roman names I have opted for the more familiar modern variants: Caesar instead of Gaius Julius (Iulius) Caesar, Antony instead of Marcus Antonius, and so on. Octavian was, as Mark Antony so rudely noted, a boy who owed everything to his name. Soon after Cleopatras suicide, Octavian (initially Gaius Octavius; later Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus) took the title Imperator and the name Caesar Augustus. To avoid confusion I refer to him as Octavian throughout. As a general rule, I use the -os ending for those of Greek heritage, so that, for example, Cleopatras youngest son becomes Ptolemy Philadelphos rather than the Latinised Ptolemy Philadelphus, but I retain the -us ending for those, like Herodotus, who are today widely known by the Latin version of their name.

All dates are BC ( BCE ) unless otherwise specified. The dynastic Egyptians counted their years by reference to the current kings reign, each new reign requiring the number system to start again at regnal Year I. The Ptolemies continued this system. The Romans used a lunar calendar of 355 days but neglected to add in the occasional month that would keep the official calendar in line with the seasons. On 1 January 46 Julius Caesar introduced a new Egyptian-inspired calendar of 365.25 days. His Julian calendar remains the basis of our own modern calendar.

Throughout the text I have used the loose term dynastic Egypt to refer to the thirty-one dynasties before the 332 arrival of Alexander the Great.

In the case of Cleopatra the biographer may approach his subject from one of several directions. He may, for example, regard the Queen of Egypt as a thoroughly bad woman, or as an irresponsible sinner, or as a moderately good woman in a difficult situation.

Arthur Weigall, The Life and Times of Cleopatra Queen of Egypt

I n approximately 3100 the independent city-states of the narrow Nile Valley and the broad Nile Delta united to form one long realm. Lines of heroic, semi-divine kings emerged to rule this new land; lines of beautiful queens stood dutifully by their side. If occasionally the kings were less heroic, and the queens less beautiful, than they perhaps could have been, it did not matter overmuch. State propaganda the convention of presenting all kings as handsome, wise and brave, and all queens as pale, passive and supportive would ensure that both kings and queens were remembered as they should have been, not as they were. Three thousand years of dynastic rule were to see at least 300 kings claiming sovereignty over the Two Lands, the unified Nile Valley and Delta. Those 300 kings were married to several thousand queens, of whom Cleopatra VII was the last.

Memories of these queens were embedded in Egypt: in tombs, on temple walls, in palace archives, funerary cults and statuary. But as dynasty succeeded dynasty, century succeeded century, the cults failed, the architecture was destroyed and all understanding of the hieroglyphic script was lost. Egypts lengthy history was still writ large on her crumbling stone walls, but now no one could read it. Only the Bible and the classical authors, Homer and Herodotus among them, offered western scholars a tantalising, selective and highly confused version of Egypts past. The dynastic queens were to remain hidden until the nineteenth century saw the development of the modern science of Egyptology.

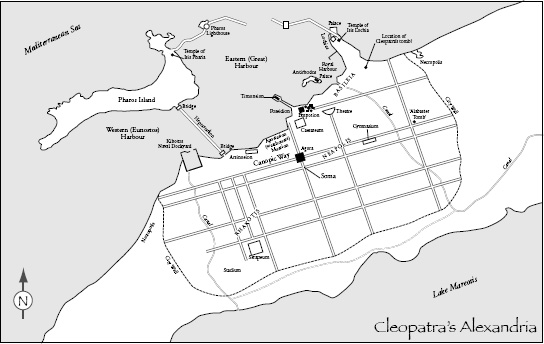

One group of queens was, however, never forgotten. The Ptolemies, the last dynasty of independent Egypt, enjoyed three centuries of rule sandwiched between the conquest of the Macedonian Alexander the Great (332) and the conquest of the Roman Octavian (30). Their stories, an integral part of Roman history, were recorded not only in Egyptian hieroglyphs, but also in Latin and in Greek. Best remembered of all was Cleopatra VII; certainly not the most successful Ptolemy, nor the longest lived, but the Ptolemy whose decisions and deeds influenced two of Romes greatest men and, in so doing, affected the development of the Roman Empire. Cleopatras story did more than survive in dusty official histories. Both Cleopatra and Egypt were seen as sexy in all modern senses of the word, and the thrilling mixture of decadence, lust and unnatural death the very obvious contrast between the seductive but decaying power of ancient Egypt and the virile, disciplined strength of Rome captured the imaginations of generations of artists and poets. Told and retold, her tale corrupted and expanded until Cleopatra evolved into a semi-mythological figure recognised throughout the world.

Next page