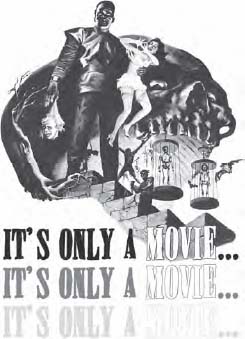

Trashfiend

Disposable horror fare of the 1960s & 1970s

Volume One

Scott Stine

www.headpress.com

Table of Contents

Articles

Interviews

Film Reviews

Sources

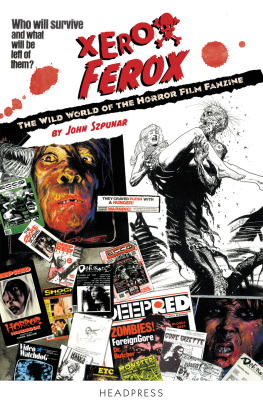

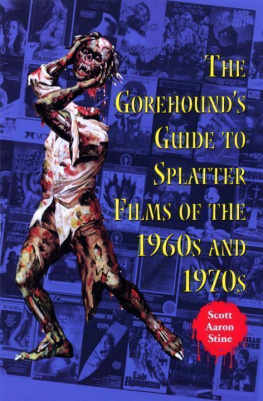

I N SPRING OF 2002, I self published the first issue of Trashfiend under my Stigmata Press imprint, a forty eight page tribute to Horror & Exploitation Fare from the 1960s & 1970s. With a modest print run of 2,000 copies, and sporting an underexposed but garish full color cover, Trashfiend picked up where its predecessor GICK! left off the previous year. Although far more comprehensive than the earlier incarnation, the primary thing that set Trashfiend apart was its unwavering devotion to media that left the greatest impression on me as a child. I had grown tired of more recent fare, which had become evident in the gradual decline of post 1980 coverage in GICK! (When I did review such films, I rarely had anything good to say about them unless, of course, they were throwbacks to the stuff that made up the cinematic soundtrack of my youth.) If any incarnation of the magazine were to survive, I had to be inspired by or at least marginally interested in the material covered within its pages. Even if many of the films and comics I wrote about were, well, trash, at least it was trash that was near and dear to my heart.

In the editorial that kicked off the first issue of Trashfiend, I made a sincere but ultimately feeble attempt to explain the main impetus behind the magazines conception: nostalgia. But it wasnt until I was wrapping up this book that I found myself one step closer to truly understanding the great cosmic force that makes the crustiest curmudgeons shuck their catch-all bah, humbugs and sigh in fond remembrance of days past. I was in the midst of writing the piece that closes this book, Sleeplessness in Seattle, when I found myself caught up in something more than casual reminiscence. I was trying desperately to save a part of my childhood that, unlike many of the things covered in this book, was slipping through the cracks of popular history. With an unprecedented urgency, I was soon consumed by the need to archive every scrap of data and trivia about this childhood obsession that I could unearth. My previous efforts to preserve all things vintage horror paled in comparison to the machinations that drove my most recent obsession. I had discovered my grail, my ark of the covenant even if friends and family alike thought it high time I purchase a one-way ticket to the bughouse, I felt justified.

As adults, we rarely experience the awe we took for granted as children. As we grow older, we gradually become more desperate to relive such moments, and we find that only through the very things that sparked our collective imaginations as children can we even come close to this now-elusive wonderment. For me, and probably many of the people reading this, it was monsters and everything devoted to them: films, comics, toys, movie magazines, what have you. That, of course, is a goodly part of what Trashfiend entails. But this beast has a particularly dark underbelly: stained and matted nether regions sullied by its need to wallow in the blood and the muck. As some of us grew up, the unattainable mature horrors that our impressionable minds were mostly spared became our newfound sirens, our need to seek out their forbidden pleasures fueled by the very fact they were once taboo. Anything that hid behind an R rating, or was placed on the top shelf of the magazine rack beyond our adolescent reach, had to be something special. As horror fans, we were always looking for something new to shock our jaded sensibilities, so it was our very nature to grasp at things concerned adults did not want us to see.

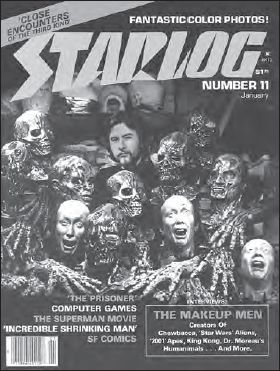

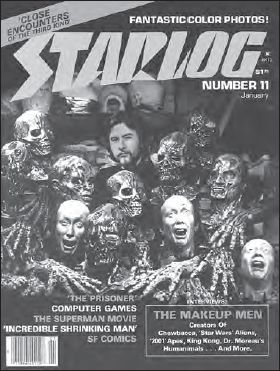

After seeing these examples of Rick Bakers effects work for The Incredible Melting Man (1977), this film capped my Top Ten Most Wanted list for years. Starlog #11 (January 1978) Starlog Communications

Most of the things considered taboo in our society are labeled as such because they appeal to our basest nature, and they are often summed up with the lowest common denominators of sex and violence. Despite the fact these distasteful subjects are the cornerstones of American entertainment, they bear a stigma that forces respectable producers and publishers to peddle their wares in a more socially acceptable fashion lest they be compared to tapeworms or other unsavory parasites that inhabit ones lower intestinal tract.

Due to its inextricable ties with these taboos, the horror genre has always shared this stigma, but never more so than during the sixties and seventies whenexcuse the mixed metaphorit pushed the envelope and exploited the inability of weary censors to assert any real control over the breached floodgates. And since the entrepreneurs who capitalized on the growing market for titillation and bloodshed produced their lurid product as cheaply as humanly possible, much of it was and is viewed as trash by the general consensus. Although I would be hard pressed to consider Warren Publications or the writings of Robert Bloch and Leslie Whitten as garbage, the fact that they are horror automatically relegates them to the position of disposable entertainment in the eyes of many people. At best, horror is kids stuff; at worst, the products of the genre are censured for fueling a savage and debauched society and regarded with utter disdain. Either way, like it or not, its trash.

Of course, some of the films covered in Trashfiend are moldering turds that should never have been disinterred, except as a target of adoring ridicule from confused individuals like myself. But the films that offer the viewer more than just an opportunity to prove their prowess as the next Joel Robinson or Mike Nelson offer something special, something unique to their respective cultures and the discombobulated decades in which they were spawned. Much of this fare displays verve, characterized by a low budget ingenuity or an unrestrained viscera that is painfully absent from anything produced in the last twenty plus years. It has heart and soul, even if it is riddled with atheromata and moral degradation.

The best of it, of course, makes some of us feel like a kid again.

Trashfiend

Disposable horror fare of the 1960s & 1970s

Key to film review abbreviations & symbols

DIR Director/s

PRO Producer/s

SCR Screenwriter/s

NOV Film novelization availability

PB Mass market paperback, SC Softcover trade or HC

Hardcover trade edition

DOP Director/s of photography

EXP Executive producer/s

MFX Makeup effects artist/s

SFX Special effects artist/s

VFX Visual effects artist/s

MUS Music composer/s

SND Soundtrack availability

CD Compact Disc or

Next page