Contents

Historical Appraisal of Walters Chronicle

by Frank E. Melvin

Introduction

And us, the men, the mean, the rank and file?

Us, tramping broken, wounded, muddy, dying?

Having no hope of duchies and endowments.

(A DAPTED INTO E NGLISH BY L. N. P ARKER , N EW Y ORK 1900)

Et nous, les petits, les obscurs, les sans-grades,

Nous qui marchions fourbus, blesss, crotts malades,

Sans espoir de duchs ni de dotations

E DMOND R OSTAND ,

LA IGLON , A CTE II, SCNE 9

T HE FRENCH REVOLUTION of 1789 seemed to many the dawn of a new eraof a new world order based on individual political and economic freedoms. On the other hand, Napoleons rule (17991815), which emerged from the Revolution, struck his subjects like a conquering whirlwind which came near to establishing France as the sole great power in the Western world. True, Napoleons reign was not only one of war and conquest, it also helped to disseminate and to root the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in many parts of Europe, initiating a process of liberalization and democratization that is the foundation of our own times. All this we see now, in retrospectto contemporaries it must have appeared differently. As we all know, profound social and political transformations exact a heavy price from those who benefit as well as from those who suffer from them, while military conquests are bought with blood, sweat, and tears. The heroic saga of Napoleons wars, and the many victories won by his armies, reaped a bountiful harvest of pride and glory for France; they are celebrated by monuments, sung by poets, exalted by historians and national myths. Even while the legacy of Napoleon recedes farther and farther from todays reality, France and the world are about to celebrate the bicentennial of his deedswitness the new Dictionnaire Napolon, the refurbishing of monuments and museums to his glory, the staging of Edmond Rostands paean, LAiglon, the exhibitions of the arts and artifacts of his times.

T HE FRENCH REVOLUTION of 1789 seemed to many the dawn of a new eraof a new world order based on individual political and economic freedoms. On the other hand, Napoleons rule (17991815), which emerged from the Revolution, struck his subjects like a conquering whirlwind which came near to establishing France as the sole great power in the Western world. True, Napoleons reign was not only one of war and conquest, it also helped to disseminate and to root the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in many parts of Europe, initiating a process of liberalization and democratization that is the foundation of our own times. All this we see now, in retrospectto contemporaries it must have appeared differently. As we all know, profound social and political transformations exact a heavy price from those who benefit as well as from those who suffer from them, while military conquests are bought with blood, sweat, and tears. The heroic saga of Napoleons wars, and the many victories won by his armies, reaped a bountiful harvest of pride and glory for France; they are celebrated by monuments, sung by poets, exalted by historians and national myths. Even while the legacy of Napoleon recedes farther and farther from todays reality, France and the world are about to celebrate the bicentennial of his deedswitness the new Dictionnaire Napolon, the refurbishing of monuments and museums to his glory, the staging of Edmond Rostands paean, LAiglon, the exhibitions of the arts and artifacts of his times.

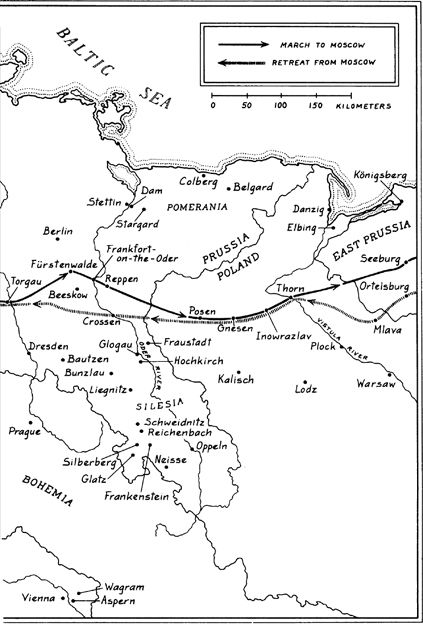

While we may recall Napoleons glory and his genuinely lasting accomplishments in law, education, and administrationboth in France and in vassal regions of Western and Central Europewe cannot forget the price paid by his contemporaries, especially the little folk, the ordinary soldiers whose blood, sweat, and toil won his battles and brought him glory. The sad truth, however, is that the common people leave few historical records, whether written or material. We are particularly fortunate when ordinary fighting men, soldiers and noncommissioned officers, leave memoirs and autobiographies recounting their part in the Napoleonic epic. There are not many of them and we should be particularly keen to preserve the few we have and to make them widely known. This is the reason for republishing an English translation of one of the very rare autobiographies by an ordinary conscript soldier, and a German at that, who had the misfortune of participating in the disastrous campaign Napoleon undertook in the vain belief that he could defeat Russia. In addition we are fortunate to publish, for the first time in English, six letters written home by soldiers in the course of the campaign itself.

For over twenty years France was at war, involving at one time or another virtually all European states. Unlike all previous European wars, even those that had lasted for decades, the revolutionary and Napoleonic campaigns were fought by conscripts drawn from the general population; in a true sense they were the first national wars that involved practically the whole people. It has been estimated that in the course of fifteen years (180015) Napoleon raised about 2 million conscripts in France aloneabout 7 percent of the total population. Little wonder that population growth in France fell dramatically, resulting in a relative decline of its population throughout the nineteenth century, at a time when England, Germany, and Prussia were having their largest population explosion ever.

Originally, the nation in arms had risen to defend the Revolution against the threat of a royalist restoration and of the elimination of the social and civic rights secured in 1789. It did not matter that, in point of fact, it was the revolutionary government that had declared war to forestall the coalition of Austria, Prussia, Russia, and England. The very success of France in driving back the armies of the monarchical alliance from its soil, and in pursuing them beyond the borders, created the conditions for a messianic drive to carry the message of liberation from the old order beyond whatsince Richelieus timeshad been claimed as the natural frontiers of France, and the installation of sister republicsBatavian, in todays Belgium, Helvetian, Cisalpine in northern Italy, etc. Although it defeated its Continental enemies, republican France could not subdue England, whose implacable enmity (under the leadership of Pitt the Younger) precluded the recognition and security of the changes, both domestic and foreign, wrought by the Revolution since 1789. At least, this is the way it was seen and interpreted at the time by both sides. England would not acquiesce to French control of the estuary of the Rhine and of the Belgian coast, and continued to organize and subsidize Continental coalitions against France. In addition, Pitt and his government believed that a reinvigorated France might pose a threat to Englands colonial empire and trade routes, especially in the eastern Mediterranean. Their belief seemed to be confirmed in 1798 by General Bonapartes attempt to conquer Egypt and the coast of what is today Syria and Lebanon and to disrupt Englands Eastern trade. Bonapartes rhetoric (and aborted negotiations with Emperor Paul I of Russia) about striking at England in India did not contribute to making English policy more accommodating and pacific. As a result, all treaties of peace concluded between France and the other powers in the last decade of the eighteenth and the first years of the nineteenth centuries proved to be only truces to be broken at the first opportunity.

T HE FRENCH REVOLUTION of 1789 seemed to many the dawn of a new eraof a new world order based on individual political and economic freedoms. On the other hand, Napoleons rule (17991815), which emerged from the Revolution, struck his subjects like a conquering whirlwind which came near to establishing France as the sole great power in the Western world. True, Napoleons reign was not only one of war and conquest, it also helped to disseminate and to root the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in many parts of Europe, initiating a process of liberalization and democratization that is the foundation of our own times. All this we see now, in retrospectto contemporaries it must have appeared differently. As we all know, profound social and political transformations exact a heavy price from those who benefit as well as from those who suffer from them, while military conquests are bought with blood, sweat, and tears. The heroic saga of Napoleons wars, and the many victories won by his armies, reaped a bountiful harvest of pride and glory for France; they are celebrated by monuments, sung by poets, exalted by historians and national myths. Even while the legacy of Napoleon recedes farther and farther from todays reality, France and the world are about to celebrate the bicentennial of his deedswitness the new Dictionnaire Napolon, the refurbishing of monuments and museums to his glory, the staging of Edmond Rostands paean, LAiglon, the exhibitions of the arts and artifacts of his times.

T HE FRENCH REVOLUTION of 1789 seemed to many the dawn of a new eraof a new world order based on individual political and economic freedoms. On the other hand, Napoleons rule (17991815), which emerged from the Revolution, struck his subjects like a conquering whirlwind which came near to establishing France as the sole great power in the Western world. True, Napoleons reign was not only one of war and conquest, it also helped to disseminate and to root the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in many parts of Europe, initiating a process of liberalization and democratization that is the foundation of our own times. All this we see now, in retrospectto contemporaries it must have appeared differently. As we all know, profound social and political transformations exact a heavy price from those who benefit as well as from those who suffer from them, while military conquests are bought with blood, sweat, and tears. The heroic saga of Napoleons wars, and the many victories won by his armies, reaped a bountiful harvest of pride and glory for France; they are celebrated by monuments, sung by poets, exalted by historians and national myths. Even while the legacy of Napoleon recedes farther and farther from todays reality, France and the world are about to celebrate the bicentennial of his deedswitness the new Dictionnaire Napolon, the refurbishing of monuments and museums to his glory, the staging of Edmond Rostands paean, LAiglon, the exhibitions of the arts and artifacts of his times.