I would not have written any book without the early encouragement of Christopher Ricks and Karl Miller. I would not have written this book without the prompting of my friends Tim Dee, of BBC Radio, and Alexandra Pringle, of Bloomsbury.

I am grateful to Mark Pearce, Alexander Pearce and Rose Boyt, and to Lindsay Duguid and Carol McDaid from whose terrific editorial advice I have greatly benefited.

Thanks, also, to Edward Horesh, Rebecca Howard and Corinna Sargood, to Xandra Bingley, Michael Holroyd, Fiona Maddocks, Diana Melly, Rick Stroud and Francis Wyndham; to my agent David Miller and, at Bloomsbury, to Holly MacDonald, Paul Nash, Anya Rosenberg, Anna Simpson, Justine Taylor and Alexa von Hirschberg. Thanks to the Authors Foundation.

I owe a particular debt of gratitude to my friends Georgina Brown, Anne Chisholm, Richard Hollis and Posy Simmonds.

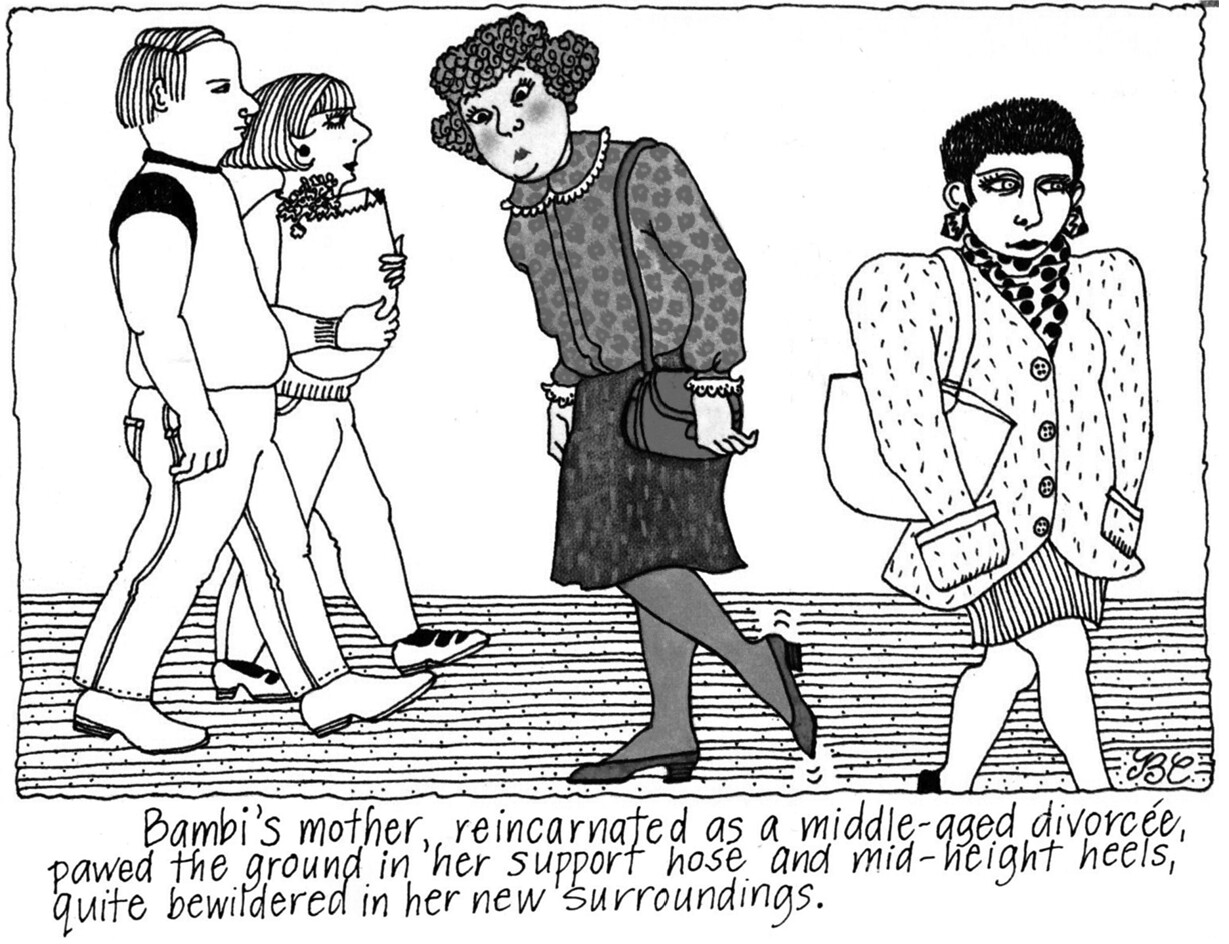

I decided Id be thin and it all got completely out of hand. It happened very quickly. She lost about thirty-eight kilos in six months and suddenly looked completely different. I would look in the mirror and not recognise myself except that I would still seem big. She was spindly, with very short curly hair, and she did not know whether this extraordinary new appearance was nice or nasty. Sometimes I looked like Byron. Often she looked like a model, though even when her shape was tight, her features were luscious. And she dressed like a 30-year-old divorce. It was 1958: she got herself up in Chanel-style suits, stilettos and black stockings, and a cream tweed duster coat which I wore with the sleeves rolled up to the elbows. The effect was smart but rakish, fast and a bit loose.

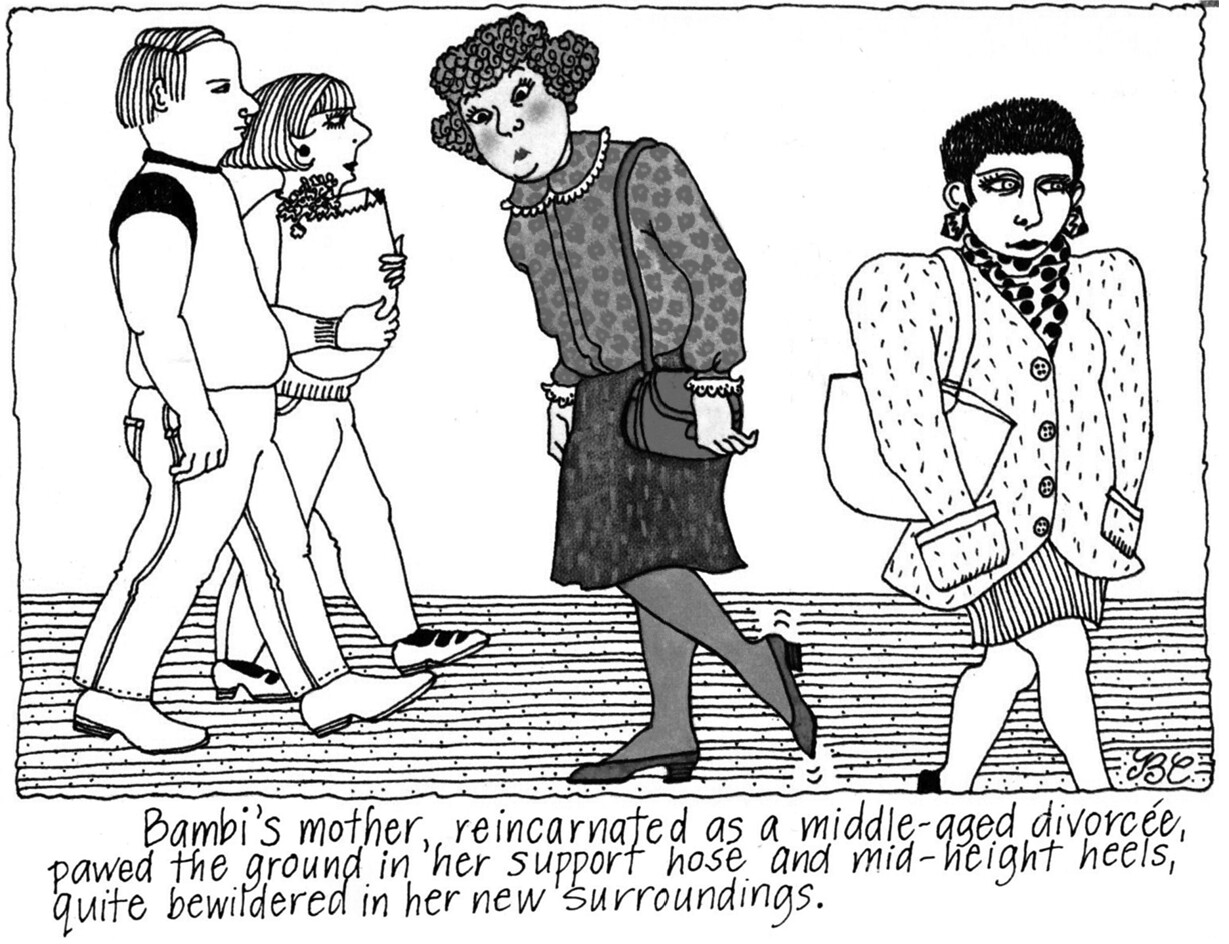

One of her postcards suggests something of this teenage shape-shifting, though it does not feature a teenager. In the late 1980s, thirty years after she had dwindled, Angela sent a droll picture from somewhere near the Eerie Canal. It captured her bemusement and her fashion sense, though not the beauty of the young, primly costumed Angela. I think this is very funny, but Im not sure why , runs her message. The black and white drawing shows a woman in a blouse with a Peter Pan collar and hair like an ornamental tea cosy. She is encased in her clothes, curved over and wary. The toe of one court shoe taps the ground; her tiny mouth is puckered; her button eyes are almost flying out of her stolid face with astonishment. The caption declares: Bambis mother, reincarnated as a middle-aged divorce, pawed the ground in her support hose and mid-height heels, quite bewildered in her new surroundings.

The dainty fawn was on Angelas mind in the eighties. In 1985 she sent a card from Boston to her friend Edward Horesh: it showed Bambi on two legs holding a missile. It was entitled Bambo.

Angela reckoned that as an acute condition her anorexia lasted for about two years, but in its chronic form it went on well into her mature life. Until she left home, until she split up with her first husband, there were many things she did not eat; right up to the birth of her son her eating patterns were still strange. For some twenty years she levelled out at about sixty-three kilos but, after Alexander, she steadily put on weight. But I wasnt worried any more. I felt so much better when I was fatter. It made me think that inside every thin woman theres a fat woman trying to get out. She went back to her pre-anorexic size.

From New South Wales came two versions of Utopia. One on each side of a card. What really fascinates me about Australia, she wrote, besides the flowers & birds & trees & exquisite mammals is this: its the stage on which the great drama of the British working class is played out on a hugely magnified scale. Thats my pet theory of the moment, anyway. Actually, it was a pretty settled theory, to which she returned when I interviewed her for the Independent on Sunday in 1991. Australia was, she declared, the most beautiful country Ive ever seen and the despised and the rejected have inherited it and... after a couple of generations they turn out to be six foot tall, incredibly good-looking, smart and republican. I think its terrific. She saw Britain becoming visibly less egalitarian all the time and Australia inspired her. It showed what America was invented for; why could Poms not do as Aussies did, and be civil without being servile? When I asked if she wanted to write about the Australian novelist Christina Stead, her response was unequivocally enthusiastic, though her description would not beguile everyone: I think shes wonderful, by Dostoevsky out of Brecht. Her piece, which appeared in the autumn of 1982, spoke with ardour of Steads importance: We have grown accustomed to the idea that we live in pygmy times. Angelas own unpygmy-sized theory about fiction was: It is possible to be a great novelist that is, to render a veracious account of your times and a bad writer that is, an incompetent practitioner of applied linguistics.

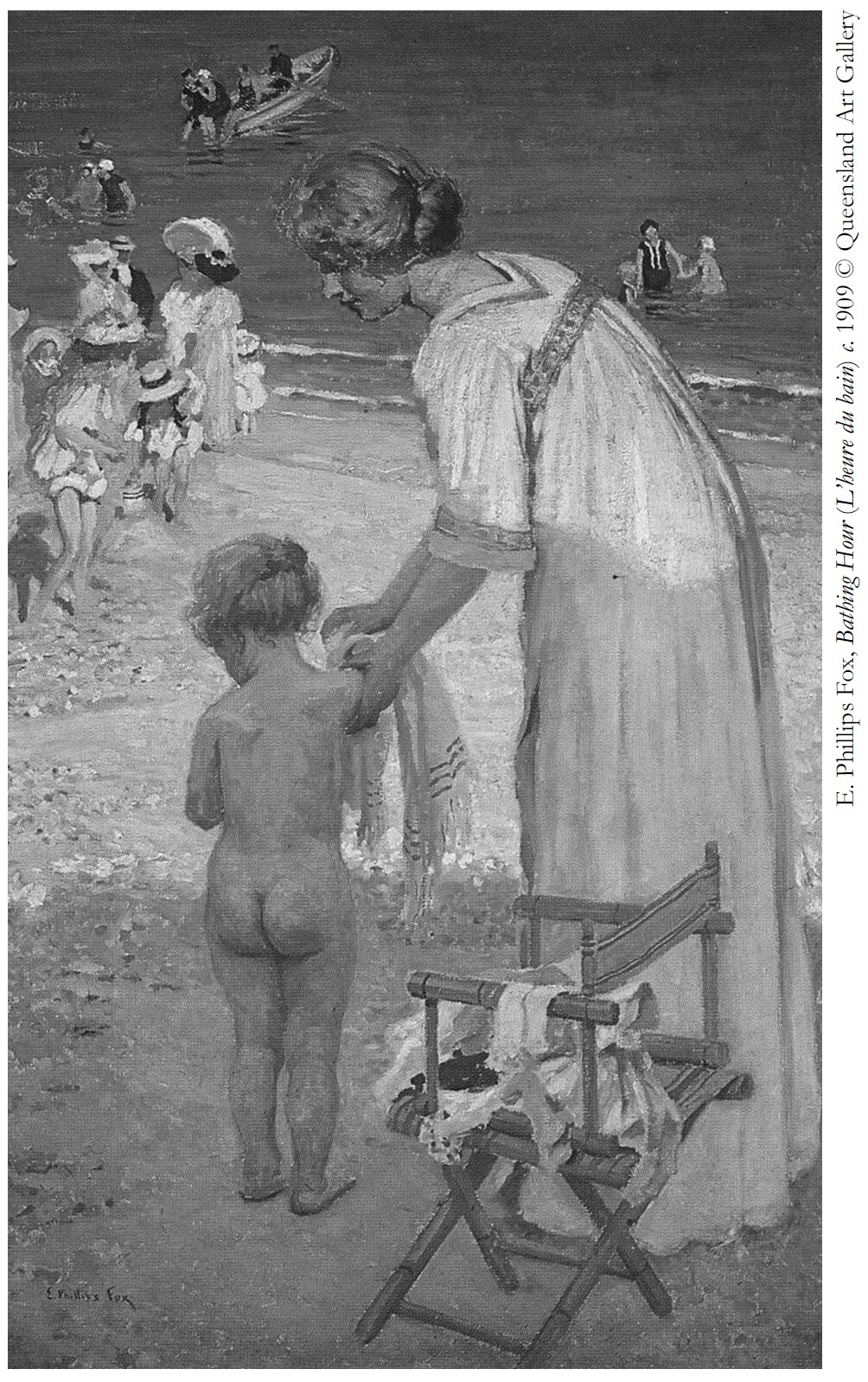

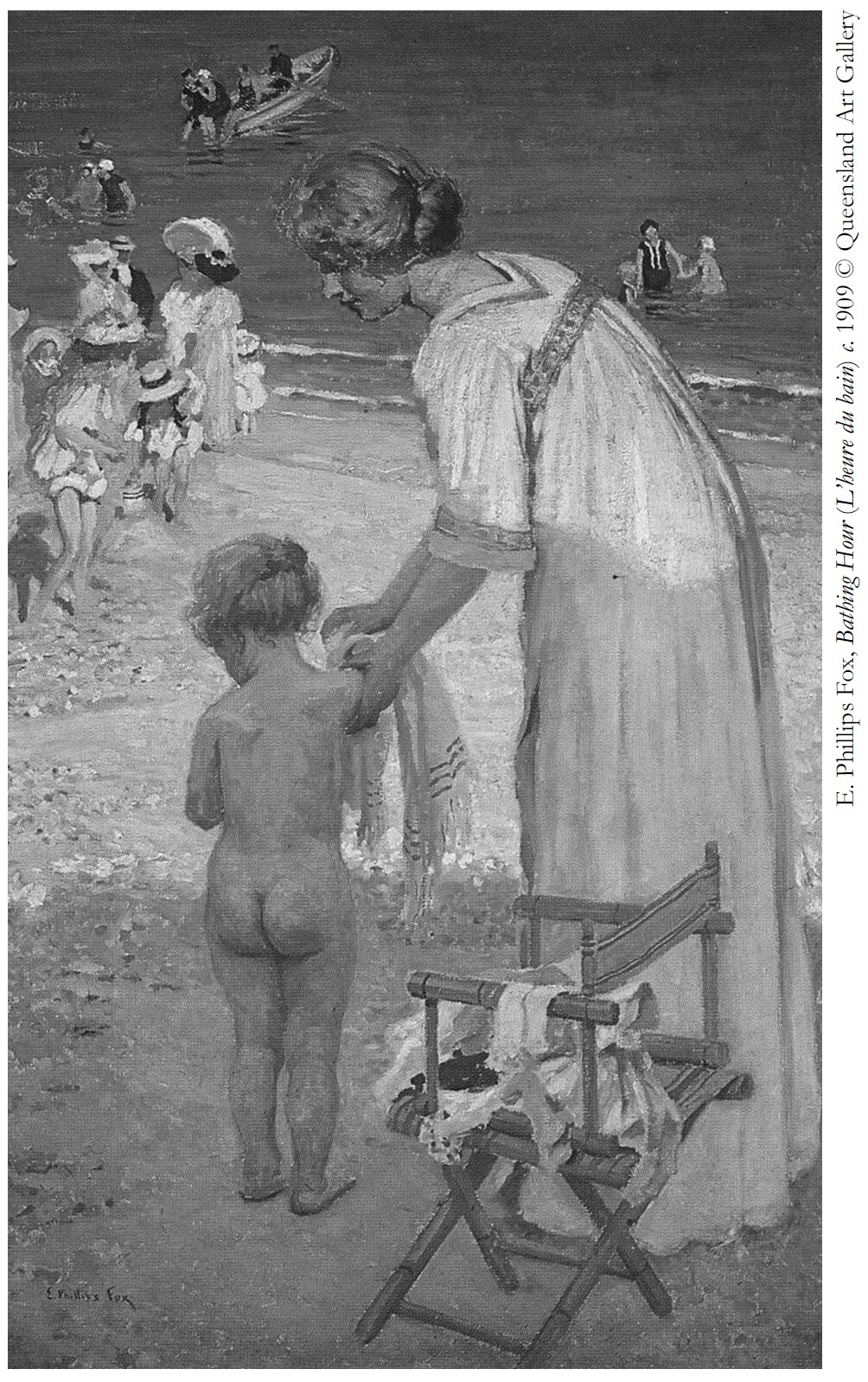

Her postcard eulogy to the Antipodes ended on a domestic note: We are fine. Alex has grown, and the picture on the other side was a maternal romance, an apolitical Eden. The Australian artist E. Phillips Fox painted On the Beach in 1909: the picture belongs to the lifetime but not the sensibility of Angelas grandmother, whom she compared to St Pancras station and who kept three copies of Foxes Book of Martyrs in her house. By the side of a green-blue sea, boaters and tucked-up skirts and lacy parasols are dawdling; in the water, sailor suits and high-necked swimming costumes join hands. In the foreground stands a woman with a copper-coloured bun and an empire-line white dress. She is towelling the arm of a small bare girl whose bottom, feet and tilted cheek are glowing red, as if she were standing by a hearth.

Angela said she believed more and more that our lives are all about our childhoods. She spoke of herself as having been a podgy little girl, of having wanted at the age of eight to be an Egyptologist, of having been a lot of peoples second-best friend at her really bad direct-grant girls grammar school in Streatham. She spoke of Alexander with astonished pleasure. His arrival also meant the beginning of a new era of concern. She knew that as long as I lived I wouldnt cease to be anxious, and cited a moment in the Royal Festival Hall when seven-year-old Alex had for seconds disappeared behind a shelf of records: My heart stopped.

I asked her during my interview to describe Mark. Big and fierce, she said. So MALE, she said with admiration to her friend and agent Deborah Rogers. Angela sheltered under his silence and supposed ferocity: My co-habitant is very frightening, she explained, when Mark arrived to collect her from a Fontana party: she tiptoed away, as if mocking her own meekness but with alacrity. Alexander was a dreamer and was becoming a word-sharpener. He invented a game called Killer Baby, and, in the cabin of a narrow boat, which his parents kept moored in Camden, told a long and intricate story about a mouse. The creature had caught a cold. A very bad cold. A cold that invited a pause for horror. A very very bad cold. Then it had caught something worse. It had caught. Extremely long pause. A taxi. Something of Angelas had been transmitted here: she always made sure when I, who, like her, did not drive, arrived at The Chase, that I knew the times of the last buses home so that I would not have to shell out for a cab.

The sight of the three of them in their narrow boat was striking. Heading to Ladbroke Grove to pick up groceries from Sainsburys, they slipped past the backs of London streets as if they were part of the citys subconscious. Mark was at the tiller, tall and bearded; Alexander was inside playing. Angela sat at the window, waving like the Queen.

Next page