Copyright 2011 by David Willman

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Bantam Books,

an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

B ANTAM B OOKS and the rooster colophon

are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Willman, David.

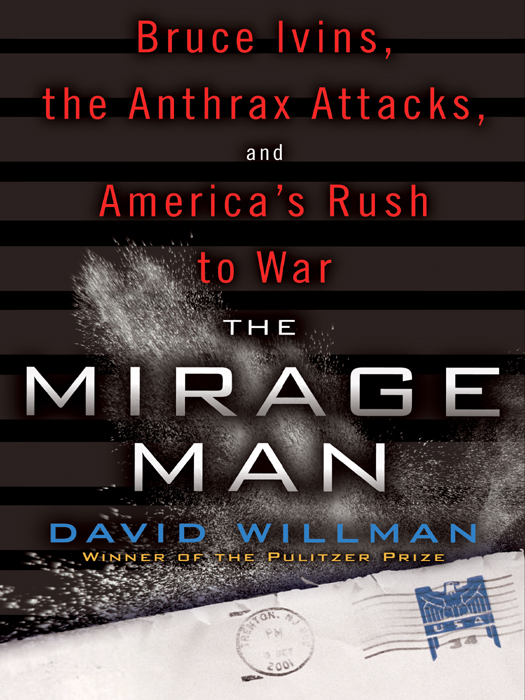

The mirage man : Bruce Ivins, the anthrax attacks,

and Americas rush to war / David Willman.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-345-53021-9

1. BioterrorismUnited StatesPrevention.

2. TerrorismUnited StatesPrevention. 3. AnthraxWar use.

4. AnthraxUnited StatesPrevention. 5. Ivins, Bruce E.

I. Title.

HV6433.35.W55 2011

363.3253092dc22 2011006232

www.bantamdell.com

Jacket design: Carlos Beltran

v3.1

For Joan, Alison, and Joseph

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

T he first of the mysterious infections emerged in South Florida, three weeks after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Robert Stevens, a sixty-three-year-old photo editor who worked at offices housing the National Enquirer and other tabloids, was diagnosed as having inhaled spores of anthrax.

President George W. Bush directed a member of his cabinet, Health and Human Services secretary Tommy Thompson, to hold a news conference on the case. Thompson played down its significance, saying there was no reason to believe Stevenss illness resulted from anything other than a natural exposure to anthrax. It appears that this is just an isolated case, Thompson said. There is no evidence of terrorism. When pressed by a reporter to explain how Stevens became infected, Thompson said health officials were unsure, but they knew he had hiked in the woods of North Carolina and drunk from a stream before falling ill.

Stevens died the day after the news conference, bringing Americans face-to-face with an unfamiliar menace. The anthrax bacterium is well known to veterinarians, much less so to physicians. Cattle and deer die every year in the United States from anthrax. But people? Almost never. (And never by drinking from a stream.) Meanwhile, a colleague of Stevens, seventy-three-year-old Ernesto Blanco, lay gravely ill in another Florida hospital. Blanco, whose job entailed sorting the piles of U.S. mail sent to the National Enquirer and other publications of American Media Inc., had been diagnosed with pneumonia. Soon after Stevenss death, further analysis revealed that Blanco, too, was infected with anthrax.

The cases were not confined to Florida. In New York, blackish sores appeared on several people who worked at or had visited the offices of the three major television networks. They had been infected when spores came in contact with their skin. The source of the anthrax at the tabloid offices in Florida remained a mystery. But in New York, two anonymous, anthrax-laced letters eventually were foundone addressed to NBC News anchor Tom Brokaw, the other to Editor of the New York Post. A similar letter landed in the epicenter of the national government in Washington, addressed to Tom Daschle, the majority leader of the United States Senate. Another letter containing anthrax was addressed to Democrat Patrick Leahy, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Each letter came within a thirty-four-cent, pre-stamped envelope that bore the image of an eagle in the upper right-hand corner. Each 3-inch-by-6-inch envelope was postmarked Trenton, New Jersey.

The notion that there was only a single, isolated case gave way to confusion and fear: The largest Senate office building was closed for decontamination. The House of Representatives was shut down. Delivery of mail was stopped at the White House. At the Supreme Court, the justices vacated the building for the first time since the structure opened in 1935.

Besides Robert Stevens, four others would eventually die of inhalational anthrax because of spores that had leaked out of letters and contaminated an untold volume of mail. Thomas L. Morris Jr. and Joseph P. Curseen Jr., postal workers in Washington, D.C., were exposed on the job. Kathy Nguyen, a hospital worker in New York City, and Ottilie Lundgren, a ninety-four-year-old woman in rural Oxford, Connecticut, were most likely infected by cross-contaminated mail. The anthrax attacks left seventeen others with nonfatal infections. Some ten thousand people at risk of infection were treated with antibiotics.

A benign portal of American life, the mailbox, had become an instrument of terror. The nation, it seemed, was in the throes of a biological attack. But by whom? The anonymous letters all contained photocopied messages with the date 09-11-01 and these three lines:

DEATH TO AMERICA

DEATH TO ISRAEL

ALLAH IS GREAT

The letters gave impetus to profound shifts in federal policy set in motion by September 11: Overwhelming majorities of Congress voted to enact the USA Patriot Act, which, among other things, eased prohibitions against electronic eavesdropping. Speculation about who sponsored the anthrax attacks outpaced verified information. President Bush spoke of a possible link to Osama bin Laden. Hawks in the administration and elsewhere suggested that Saddam Hussein might be responsible. Their remarks, coupled with the presidents emphatic statements that Saddam possessed biological and chemical weapons and might even be developing nuclear ones, intensified the clamor for war. Wildly inaccurate media accounts stoked the hysteria. In March 2003, the United States invaded Iraq.

The letter attacks gave rise to Bushs signature domestic policy response, Project BioShield, which provided billions of dollars to develop vaccines or antidotes against anthrax and other threat agents. The government also began bankrolling construction of dozens of laboratories equipped to conduct experiments with deadly biological pathogens. Each facility promised to expand the nations research capacitybut created new security risks by granting thousands of scientists unprecedented access to the tools of biowarfare.

Within days of the first anthrax death, the FBI launched what would become one of the most far-reaching investigations in the annals of law enforcement. Together with the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, the FBI conducted thousands of interviews and scores of searches. The investigators traveled to six continents to question potential witnesses. The case soon focused on one suspect above all othersDr. Steven Hatfill, a scientist who had worked for two years at the U.S. Armys biowarfare research center at Fort Detrick, Maryland.

In numerous leaks to the news media, officials with access to investigative details made clear their belief that Hatfill was the anthrax killer. Investigators delivered the same message privately to congressional leaders and to those at the highest levels of the Bush administration. Yet the FBI never formally accused Hatfill of a crime. His reputation in tatters, Hatfill sued the FBI and the Justice Department.

Another scientist at Fort Detrick remained far less visible, although he was well known to investigators. The FBI had in fact called upon this scientist, Bruce Ivins, for early assistance with the investigation. When it came to the poorly understood complexities of Bacillus anthracis, the investigators, who had never before tried to solve an anthrax killing, could not have found a better-qualified expert at Fort Detrick. Ivins was an accomplished microbiologist who had established himself as an important anthrax researcher for the Army during the run-up to the 1991 Persian Gulf War, when military leaders feared that Saddam Hussein would unleash the bacterium on the battlefield.