Copyright 2012 by Gerard Helferich

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Text design: Sheryl Kober

Layout: Justin Marciano

Project editor: Ellen Urban

Maps: Trailhead Graphics Inc. Morris Book Publishing, LLC

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Helferich, Gerard.

Stone of kings : in search of the lost jade of the Maya / Gerard Helferich.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7627-6351-1

1. MayasImplements. 2. MayasJewelry. 3. MayasAntiquities. 4. Jade implementsCentral America. 5. Jade jewelryCentral America. 6. Jade art objectsCentral America. 7. Central AmericaAntiquities. I. Title.

F1435.3.I46H45 2012

972.81dc23

2011035824

To Florence Hood Nicholas,

who has lived a quiet life

of great adventure

PROLOGUE

I ts a warm April evening on the cusp of the rainy season. Were seated under the long, tiled colonnade of a centuries-old house in Antigua, in the highlands of Guatemala. My wife, Teresa, and I have come to do some research for a travel publisher. But as the shadows deepen and the volcanoes disappear into the darkness, our hostess begins to spin a remarkable tale.

A tall, blonde gringa of a certain age, she is the sister of a friend back in our adopted home of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. But you might say we were introduced by Alexander von Humboldt. A few years ago, our hostesss husband read my Humboldts Cosmos , an account of the great German naturalists New World odyssey. As I relate in the book, Humboldt was born into an aristocratic Prussian family during the Second Great Age of Discovery, when titanic figures such as James Cook and Louis-Antoine de Bougainville were completing their historic circumnavigations of the earth. Though the young Alexander longed to make a grand journey of his own, his mother pressed him into a more sensible career as a government inspector of mines. But on coming into his fortune after his mothers death, Humboldt persuaded King Carlos IV to entrust himnot yet thirty, a foreigner, and a Protestantwith the first extensive scientific exploration of Spains New World empire. And during five astonishing years, from 1799 to 1804, Humboldt, with his companion Aim Bonpland, blazed a hazardous, six-thousand-mile swath through Latin America, from Cuba to Peru, from the Andes to the Amazon, opening the continent to science and transforming himself into one of the most celebrated figures of his age.

For reasons I dont fully appreciate at the time, our hostesss husband has been moved by Humboldts story, and he has invited me to drop by if Im ever in Antigua. When Teresa and I arrive, hes too ill to see us, but his wife graciously invites us for a drink. I expect a simple social call; then she begins her story. A story of jade. Like most people, Ive never thought much about the stonewhere it comes from, why its important or interesting, even what it is. But as her voice echoes down the darkening colonnade, I feel the mounting exhilaration of a writer encountering his subject.

When I return from Antigua, I begin reading about jade and pestering archaeologists and geologists, learning everything I can about its formation, its lore, its ties to the great cultures of the past. I also discover a connection I hadnt expected. In Humboldts Cosmos , I wrote about his admiration for Americas native peoples and his pioneering studies of cultures such as the Aztec and the Inca. Among the tens of thousands of specimens Humboldt brought back at the end of his journey were some pre-Columbian figurines, one of which was reproduced in my book.

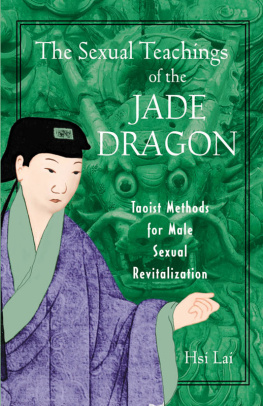

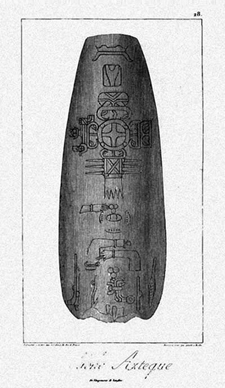

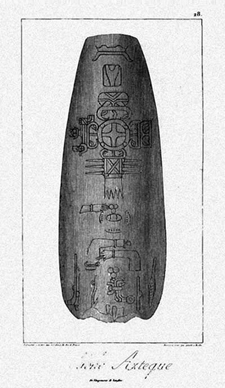

The enigmatic Humboldt Celt, as it appeared in Humboldts Researches Concerning the Institutions and Monuments of the Ancient Inhabitants of America with Descriptions and Views of Some of the Most Striking Scenes in the Cordilleras.

But this time, my thoughts turn to another of Humboldts souvenirs. Its a celt, a polished stone shaped vaguely like the head of an axe, which was presented to the explorer by Andrs Manuel del Ro, professor of mineralogy at Mexico Citys national school of mining. Bluish in color, about nine inches long and a little better than three inches wide, the celt had lost its pointed end. The rest was incised with a dozen rebus-like symbols. Though a few were recognizablea pair of crossed arms, a hand, an ornate cross, perhaps an oar and a spear throwertheir significance was long forgotten. As Humboldt realized, the celt was carved from jade.

Back in Europe, Humboldt presented the artifact, which he believed to be an Aztec hatchet, to his sovereign, Frederick Wilhelm III of Prussia, for display in the royal cabinet of curiosities, a collection of natural history and anthropological specimens. For the next century and a half, the Humboldt Celt, as it came to be known, remained in Berlin. Though the stones message was inscribed in no known language, that didnt stop a scholar named Philipp J. J. Valentini from venturing an impressively detailed translation in 1881:

The man, in whose tomb the sacred stone was laid, stood high in rank and personal achievements. He never failed to appear before his gods to burn the incense on the temples brazier. He caused his arms to bleed and sacrificed his blood by sprinkling it in the glowing embers. When he entered the tlachco court, his was the victory. Like darts, his balls of hule were flying through the ring. He had no equal in bringing to the ground his foe by tlacoctli , and when he seized the oar and went upon the river, he was certain to bring home the sweet turtle quivering on the barb of his harpoon. Great was the strength of his arms; the heavy cudgel was the toy of his youth. There was no deer so distant nor its legs so fleet, that his eyes could not spy or his lasso reach.

Eventually, the celt ended up in the national ethnographic museum on Stresemannstrasse. When that building was destroyed during the Second World War, the Humboldt Celtshattered, looted, or perhaps buried in the rubblewas lost.

As I immerse myself in my new subject, the errant celt takes on a meaning for me as well, more vague but perhaps no less idiosyncratic than that suggested by Philipp Valentini: With its strange carvings and unexplained disappearance, it seems to embody the enigma of jade.

To peoples such as the Maya, jade was not only heartbreakingly beautiful but supremely powerful, and no substance was more eagerly acquired or more jealously guarded. Yet when Alexander von Humboldt arrived in Latin America, a millennium after the Maya decline and three centuries after the Spanish Conquest, no one knew where the ancients had found their jade. Humboldt searched for the source, to no avail. Notwithstanding our long and frequent excursions in the Cordillera of both Americas, he wrote, we were never able to discover a rock of jade; and this rock being so scarce, the more we were surprised at the immense quantity of jade hatchets, which are found on digging in plains formerly inhabited, from the Ohio to the mountains of Chile. Humboldt exaggerated the range of jade artifacts, but by the time his keepsake went missing, the mystery of the stones origin still hadnt been solved. Like the Humboldt Celt, the Mayas jade mines had vanished.