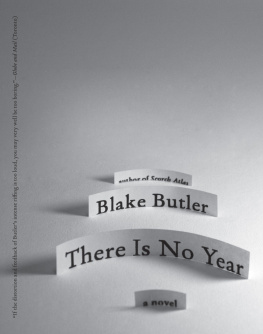

the

splendid

things

we

planned

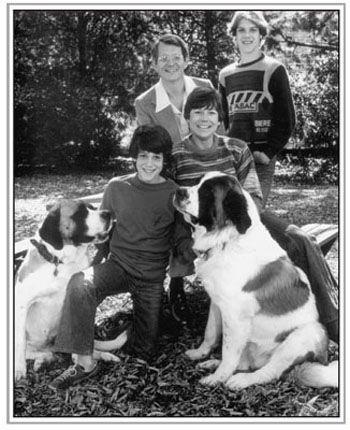

a family portrait

blake bailey

w. w. norton & company new york london

To Marlies and Scott

Thats one of the damnedest things I ever found out about human emotions and how treacherous they can bethe fact that you can hate a place with all your heart and soul and still be homesick for it. Not to speak of the fact that you can hate a person with all your heart and soul and still long for that person.

Joseph Mitchell, Joe Goulds Secret

table of contents

the

splendid

things

we

planned

M y brother Scott was born in 1960 and screamed a lot as a baby, until one night my parents left him in their dorm room at NYU and proceeded to the roof, where a locked door prevented them from splattering themselves on a MacDougal Street sidewalk. In later years theyd tell the story for laughs, but I wonder if they saw the humor at the time. In the funny version I always heard, there was no locked door, and they carried Scott to the roof with them; the question was whether to throw him or themselves off. For a while they stood there, staring down at the lights of Washington Square while my brother yowled and yowled as if to egg them on to their doom. Not wishing to inflict this racket on the populace, perhaps, they retreated downstairs with the burden still in tow.

Life had been a heady affair up to then. My father, Burck, had come to Manhattan as a Root-Tilden Scholar at NYU Law, on his way to fulfilling his promise as the most gifted young man in Vinita, Oklahoma, a gray blur off the Turnpike between Tulsa and Joplin. He was whip smart, top of his class, American Legion Citizen of the Year, even something of an athlete; he insisted on playing football even thoughat five-ten, 135 poundshe wasnt really big enough and kept getting banged up, almost losing a leg to gangrene when it was stepped on by a steel cleat. My mother, Marlies, was an offbeat German girl who bore a striking resemblance to Shirley MacLaine. Shed come to the States a couple of years before, age nineteen, and took an apartment at the Hotel Albert with two Jewish girls who thought she was a kick and vice versa. She and my father had met on a blind date. Both were escaping a home life they found oppressive, unworthy of the personages they hoped to become. Then my mother got pregnant.

My father supplemented his scholarship by working at a liquor store, while my mother had to stay home with the baby. Home was a tiny room with a Murphy bed, on which my mother sat in a funk all day, hour after hour, while little Scott emitted one heart-shriveling shriek after another. He rarely slept. Sometimes his eyes would glaze as he screamed; hed stare at some vague speck on the ceiling, as if screaming helped him concentrate on some larger plan. For her part (I imagine) my mother dwelled ruefully on the recent but dead past. Shed been having such a good time in America. Before marrying my fatherbefore this she worked in the gourmet shop at Altmans and got plenty of dates; her English was excellent, she was wistfully intellectual, and she liked to argue in favor of atheism and Ayn Rand.

The doctor had given her some sleeping drops for the baby, which she ended up taking instead. Meanwhile shed gone a little mad with postpartum depression. She couldnt keep food down, and had pretty much given up on eating. I had huge milk-filled breasts and the waist of a ten-year-old, she remembered, wondering whether her milk had been somehow tainted by the dreariness of it all. Plus her crotch itched something fierce; the doctor had sloppily shaved her prior to slitting her perineum.

Many years later my mother and I had a lot of tipsy conversations about all this. Where did we go wrong? conversations. One night she started sobbingdrunk or not, she cried only in moments of the most terrible griefand said shed once done a terrible thing when Scott was a baby. This was around the time my father had almost died from a bleeding ulcer. As usual hed been studying in the bathroom late at night, sitting on the toilet with tissue in his ears, when my mother heard a thunk (his head hitting the sink) and found him passed out in a fetal slump. While he was away at St. Vincents, Scott redoubled his efforts to nudge our mother into the abyssscreaming and screaming and screaming as if to berate her for some ineffable crime against humanity. Marlies, in turn, tried frantically to calm him: nursed him with her aching breasts, changed and rechanged his diaper, shushed and cuddled and pleaded with him. Finally, beyond despair, she muffled him with a pillow. If the baby had struggled, writhed a bit, she might have forgotten herself and held the pillow in place a moment too longbut he only lay there as if to emphasize his helplessness. Even then, Scott had a knack for self-preservation in spite of everything.

When I later mentioned the episode, Marlies vehemently denied it. Shes denied it ever since. So maybe she was only dreaming out loud that night, unburdening herself of a persistent but intolerable thought.

A crucial difference between my brother and me was that he spoke German and I didntwhich is to say, he inherited my mothers facility and I inherited my fathers all but total lack thereof; in fact, it became another aspect of Scotts curious bond with my mother, as theyd lapse into German whenever they wished to speak or yell privately while in my presence. Scott learned the language at age thirteen, during a solo trip to Germany to visit our grandparents, and on return he contrived to insult me in a way that would call attention to this superiority. I was ten and didnt brush my teeth as often as I might, so he dubbed me Zwiebel Mund, or onion mouth. It stuck: he never again called me anything else unless he was angry or discussing me with some third party.

Mind, there were many variations. Usually he called me Zwieb, and what had begun as an insult assumed, over the years, the caress of endearment. In its adjectival formZwiebish, Zwiebian, etc.it meant something like: pompous but in a kind of lovable, self-conscious way (as he saw it), or benignly self-absorbed (ditto) and given to odd, whimsical pronouncements because of this. The nuances were elusive and mostly lost on the world beyond my brother and me. There were also ribald noun variationsZwiebel-thang, Zwiebonius, etc.or, when he was particularly delighted (high-pitched) or admonishing (low), hed throw his head back and say Zwiiieeeeeeeeb! with a faint, nasal Okie twang to the vowel sound. My brother had more of an accent than I, especially as we got older, due in part to the different company we kept and perhaps because he was often stoned. Kind people tell me I have little or no trace of an Oklahoma accent. If so, I have my mother to thankher own English sounds, if anything, vaguely Britishthough my father too has mostly purged his deep, lawyerly voice of its Vinita origin, except when hes trying to connect with the common folk, and in any case he still pronounces the a in pasta like the a in hat.

And what, in turn, did I call Scott? I called him a very matter-of-fact (or deploring) Scott . No endearments on my end.

AFTER NYU, MY father was hired by Morrison, Hecker, Cozad & Morrison in Kansas City, where he and my mother and Scott lived in an apartment complex called the Village Green. I picture their two-story row house as a rather drab, dispiriting place, but of course it was paradise next to Hayden Hall at NYU. Life got steadily better. Burcks colleagues at the firm were a festive, hard-drinking bunch who thought Marlies was a hoot (she danced on tables at parties), and meanwhile shed found some kindred women through volunteer work at the Nelson Art Gallery. One of her better friends was a gorgeous trophy wife who used to complain bitterly about things, and finally hanged herself in the attic.

Next page