If in the end he still remains something of a mystery, we should not be surprised: for every human being is a mystery and nobody knows the truth about anybody else. A. A. Milne

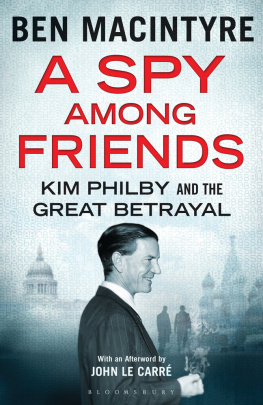

T his memoir is the previously unknown story of the long friendship between Kim Philby and Ian Innes Tim Milne, an association which lasted for thirty-seven years, from the time they first met at Westminster School in September 1925 until Philbys defection to Moscow in January 1963. It is the only first-hand account of the Philby affair ever written from the inside by someone who served in the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) and worked alongside the so-called KGB master spy. Philbys own book was of course written in Moscow under KGB supervision and is therefore suspect.

From Westminster Milne and Philby proceeded to different universities Philby to Trinity, Cambridge and Milne to Christ Church, Oxford but they travelled together in central Europe during university holidays and remained close.

Philby joined SIS in September 1941. Milne followed him some weeks later, recruited by Philby as his deputy and serving alongside him in Section V for most of the war years. Like Philby, Milne stayed on in SIS after the war and they remained professional colleagues as well as friends until Philbys dismissal from the service in 1951. Their friendship continued for a dozen years after this until Philbys flight from Beirut.

When the Philby story first broke and became a hot news item Tim Milne was identified in print as being a close friend of Kim Philby, and although Milne was then still a serving officer in SIS, press interest in him became intense. I was working on the Insight team at the Sunday Times and the editor asked me to find Milne and try to persuade him to talk about his long association with Philby, particularly the holidays they had spent in Europe together. Was there a clue to be found there that explained Philbys treachery? Milne politely sent me on my way, pleading the restrictions of the Official Secrets Act. He retired from SIS in October 1968, continuing in government service for another seven years, but he never spoke publicly on the subject of his friendship with Philby, although in later years he was invariably courteous to the various authors who approached him for information.

Tim Milne died at the age of ninety-seven in 2010 and his obituary in TheTimes stated in part that his feelings on learning of his old friends sustained betrayal of his colleagues and his country can only be a matter of conjecture: he himself maintained great discretion on the subject for the rest of his life. It was not widely known, outside his family and former service, that he had in fact written a very full and frank account of his association with Philby, nor that his memoir had been accepted for intended publication in 1979. However, before any such publication could happen, Milne was required to submit the manuscript to SIS and obtain their permission to publish, in view of the confidentiality obligations incumbent on him. In the event, permission was denied and Milne reluctantly had to abandon the project.

Free of these obligations today, Milnes daughter has now given permission for her fathers memoir to be published, and this account of a friendship which lasted almost forty years and included a professional relationship for ten of those can now be related in full. Over the past forty-seven years, since the first articles on Philby were written, a considerable number of other articles, TV documentaries and drama treatments, as well as countless books, have appeared: none, however, have been written by someone who knew him as well, or for as long a period, as Tim Milne.

It comes as little surprise that this memoir is so elegantly and well written, given that Tims father, Kenneth John Milne, was a contributor to Punch magazine and a close literary collaborator with his brother (Tims uncle), Alan Alexander Milne, the author of the Winnie-the-Pooh books among others. Tims own inherited and natural writing excellence was also in demand after he left Oxford, as he worked for five years as a copywriter for a leading London advertising agency before war intervened.

Although Kim Philbys treachery was to cause Milne personal distress and considerable professional difficulties, he writes about his long association with Philby without any hint of rancour or bitterness. When I interviewed Philby in Moscow in 1988, he told me, I have always operated at two levels, a personal level and a political one. When the two have come into conflict I have had to put politics first. This conflict can be very painful. I dont like deceiving people, especially friends, and contrary to what others think, I feel very badly about it.

It is not known whether Milne knew of these statements, as undoubtedly he was one of the friends to whom Philby was referring . When the news came that Philby had died, in Moscow on 11 May 1988, Tims daughter asked, I suppose you have mixed feelings? Milne replied, No, for me he died many years ago.

One recent author on the subject of Philby wrote, Many individuals exert a fascination over the public, but rarely has one individual held such a fascination for so many years for a country that they betrayed. The year 2013 marked the fiftieth anniversary of Philbys defection to Russia and twenty-five years since his death in Moscow: following these anniversaries, the publication of Tim Milnes full account of his close friendship and association with this most unusual man may now provide readers and historians alike with the closing chapter on the story of Kim Philby.

Phillip Knightley

January 2014

[Editors note: These notes were compiled (not by the author) some time after the book was written.]

Notes

. From childhood and for the rest of his life, Milne was known to his family and friends as Tim.

. Phillip Knightley, Bruce Page and David Leitch, Philby: The Spy Who Betrayed a Generation, Andr Deutsch, London, 1968.

. A lengthy obituary was published in The Times on 8 April 2010.

. For an excellent account of the life of A. A. Milne and the close relationship with Kenneth (who died in 1929) and Kenneths widow and children, see Anne Thwaite, A. A. Milne: His Life, Faber, London, 1990.

. Phillip Knightley, Philby: The Life and Views of the KGB Masterspy, Andr Deutsch, London, 1988, p. 219.

. Rufina Philby, interview with the Sunday Times, June 2003.

. Gordon Corera, The Art of Betrayal: Life and Death in the British Secret Service, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2011, p. 92.

T his book is dedicated to the memory of my parents. My father wrote his account in longhand, and my mother typed and retyped the manuscript many times. Though it is ostensibly my fathers book, in reality it was a joint project which involved them both for several years. I know how very pleased they would have been to see the publication of this memoir, even so long afterwards.

Most, if not all, of my fathers colleagues and contemporaries in SIS have now died, and Kim Philby himself died more than twenty-five years ago. However, this is one story which never seems to lose its fascination for many, despite the half-century which has passed since Philbys defection to Russia.

The final version of my fathers manuscript was accepted for publication both in Britain and in America in 1979. I remember how disappointed and discouraged my father was when he was denied permission to publish. The manuscript was subsequently abandoned, and during his lifetime my father never revisited the possibility of publication.

Considerable thanks must now go to my collaborator, Richard Frost, who first encouraged me to proceed with this project, and then worked tirelessly on the editing and the source notes, before acting as intermediary between me and Biteback Publishing. Without Richard, it is certain that the typescript of this book would still be languishing in a ring binder, unseen.