()

Copyright 2013 by Stephen W. Hawking

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Bantam Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

B ANTAM B OOKS and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Illustration credits appear on .

Published simultaneously in the United Kingdom by Bantam Press, part of Transworld Publishers, a member of The Random House Group, London.

Portions of this work originally appeared in different form as part of lectures given by the author throughout the years.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Hawking, Stephen.

My brief history / Stephen Hawking.

pages cm

eISBN: 978-0-345-53913-7

1. Hawking, Stephen, 1942 2. PhysicistsGreat BritainBiography. 3. Cosmology. 4. Black holes (Astronomy) I. Title.

QC16.H33A3 2013

530.092dc23

[B}

2013027938

www.bantamdell.com

Jacket design: Kathleen Lynch/Black Kat Design

Front-jacket photograph: courtesy of the author/

Gillman and Soame UK

v3.1

CONTENTS

()

1

CHILDHOOD

M Y FATHER, FRANK, CAME FROM A LINE OF TENANT farmers in Yorkshire, England. His grandfathermy great-grandfather John Hawkinghad been a wealthy farmer, but he had bought too many farms and had gone bankrupt in the agricultural depression at the beginning of this century. His son Robertmy grandfathertried to help his father but went bankrupt himself. Fortunately, Roberts wife owned a house in Boroughbridge in which she ran a school, and this brought in a small amount of income. They thus managed to send their son to Oxford, where he studied medicine.

My father won a series of scholarships and prizes, which enabled him to send money back to his parents. He then went into research in tropical medicine, and in 1937 he traveled to East Africa as part of that research. When the war began, he made an overland journey across Africa and down the Congo River to get a ship back to England, where he volunteered for military service. He was told, however, that he was more valuable in medical research.

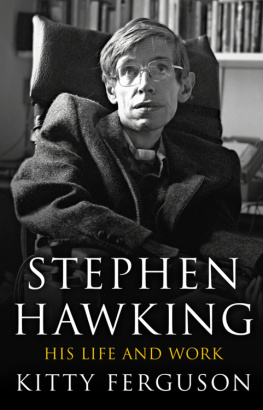

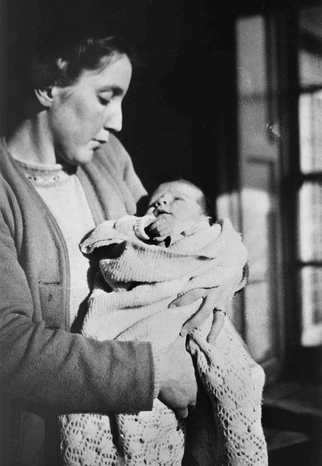

My father and I ()

)

My mother was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, the third of eight children of a family doctor. The eldest was a girl with Down syndrome, who lived separately with a caregiver until she died at the age of thirteen. The family moved south to Devon when my mother was twelve. Like my fathers family, hers was not well off. Nevertheless, they too managed to send my mother to Oxford. After Oxford, she had various jobs, including that of inspector of taxes, which she did not like. She gave that up to become a secretary, which was how she met my father in the early years of the war.

I WAS born on January 8, 1942, exactly three hundred years after the death of Galileo. I estimate, however, that about two hundred thousand other babies were also born that day. I dont know whether any of them was later interested in astronomy.

I was born in Oxford, even though my parents were living in London. This was because during World War II, the Germans had an agreement that they would not bomb Oxford and Cambridge, in return for the British not bombing Heidelberg and Gttingen. It is a pity that this civilized sort of arrangement couldnt have been extended to more cities.

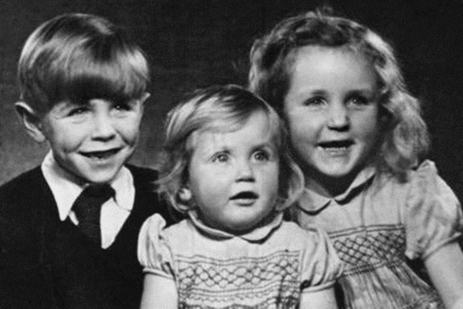

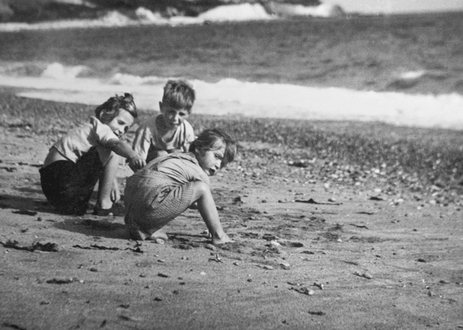

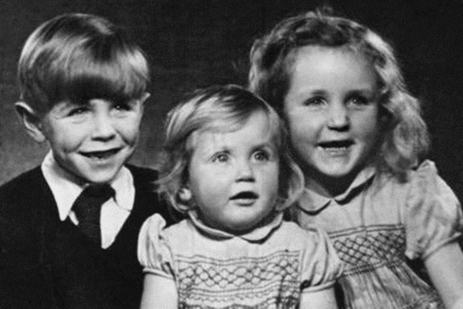

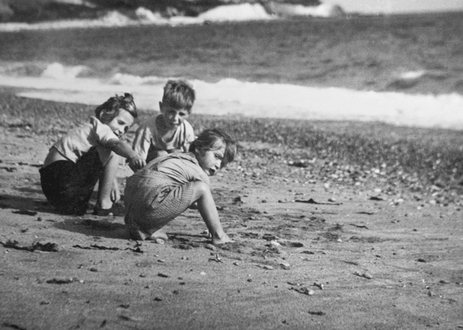

We lived in Highgate, in north London. My sister Mary was born eighteen months after me, and Im told I did not welcome her arrival. All through our childhood there was a certain tension between us, fed by the narrow difference in our ages. In our adult life, however, this tension has disappeared, as we have gone different ways. She became a doctor, which pleased my father.

My sister Philippa was born when I was nearly five and better able to understand what was happening. I can remember looking forward to her arrival so that there would be three of us to play games. She was a very intense and perceptive child, and I always respected her judgment and opinions. My brother, Edward, was adopted much later, when I was fourteen, so he hardly entered my childhood at all. He was very different from the other three children, being completely non-academic and non-intellectual, which was probably good for us. He was a rather difficult child, but one couldnt help liking him. He died in 2004 from a cause that was never properly determined; the most likely explanation is that he was poisoned by fumes from the glue he was using for renovations in his flat.

)

)

MY EARLIEST memory is of standing in the nursery of Byron House School in Highgate and crying my head off. All around me, children were playing with what seemed like wonderful toys, and I wanted to join in. But I was only two and a half, this was the first time I had been left with people I didnt know, and I was scared. I think my parents were rather surprised at my reaction, because I was their first child and they had been following child development textbooks that said that children ought to be ready to start making social relationships at two. But they took me away after that awful morning and didnt send me back to Byron House for another year and a half.

At that time, during and just after the war, Highgate was an area in which a number of scientific and academic people lived. (In another country they would have been called intellectuals, but the English have never admitted to having any intellectuals.) All these parents sent their children to Byron House School, which was a very progressive school for those times.

I remember complaining to my parents that the school wasnt teaching me anything. The educators at Byron House didnt believe in what was then the accepted way of drilling things into you. Instead, you were supposed to learn to read without realizing you were being taught. In the end, I did learn to read, but not until the fairly late age of eight. My sister Philippa was taught to read by more conventional methods and could read by the age of four. But then, she was definitely brighter than me.

We lived in a tall, narrow Victorian house, which my parents had bought very cheaply during the war, when everyone thought London was going to be bombed flat. In fact, a V-2 rocket landed a few houses away from ours. I was away with my mother and sister at the time, but my father was in the house. Fortunately, he was not hurt, and the house was not badly damaged. But for years there was a large bomb site down the road, on which I used to play with my friend Howard, who lived three doors the other way. Howard was a revelation to me because his parents werent intellectuals like the parents of all the other children I knew. He went to the council school, not Byron House, and he knew about football and boxing, sports that my parents wouldnt have dreamed of following.