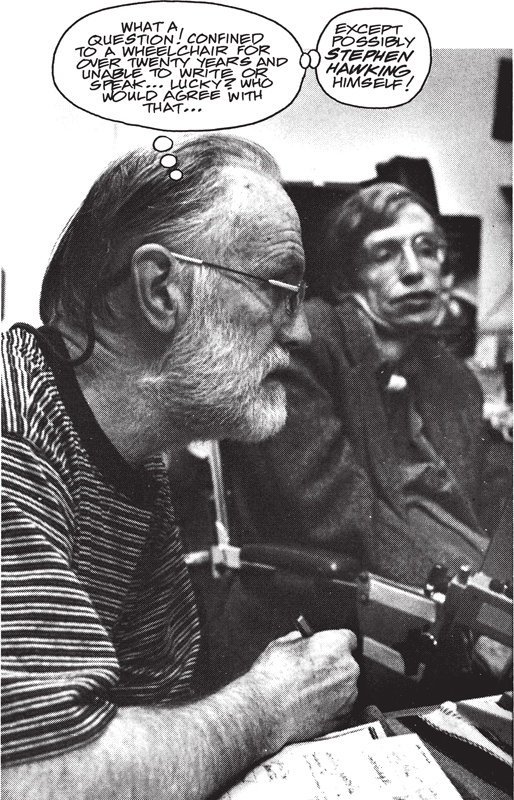

On 19 October 1994, the author of this book interviewed Stephen Hawking. He began with a question that might seem daring, if not impertinent. Did Hawking consider himself lucky?

WHAT A QUESTION! CONFINED TO A WHEELCHAIR FOR OVER TWENTY YEARS AND UNABLE TO WRITE OR SPEAK LUCKY? WHO WOULD AGREE WITH THAT EXCEPT POSSIBLY STEPHEN HAWKING HIMSELF!

Lets go back a bit

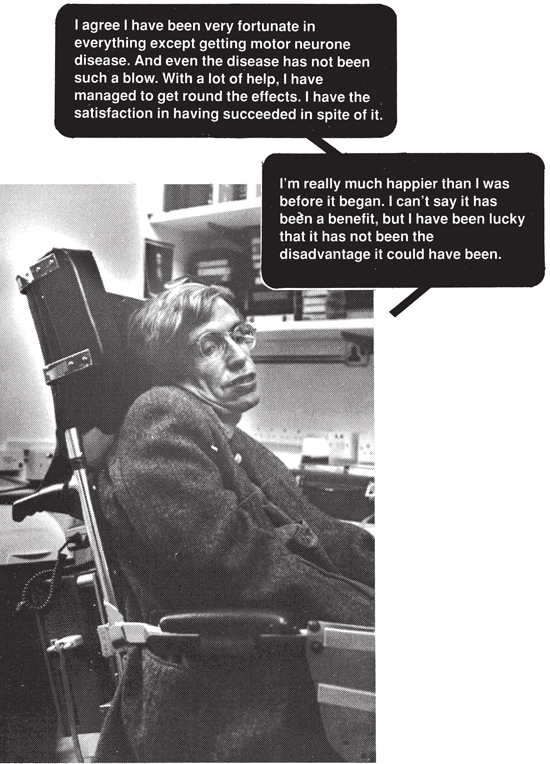

Everyone knows of Hawkings bad luck. It began one afternoon in the spring of 1962 when he found it very difficult to tie his shoelaces. He knew something was drastically wrong with his body. That year he had talked his way into a first degree at Oxford University and was accepted as a postgraduate student at Cambridge. But he had contracted amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS for short, the motor neurone disease. It is incurable and fatal. Doctors gave him two years to live.

As the tabloid press and the paperback biographies would have us believe, Hawking spent the next several months in deep depression in his university digs, drinking and listening to Wagner. To add to his bitterness, he was told that he would not have the famous cosmologist Fred Hoyle (b. 1915) as his research adviser, the reason he chose Cambridge in the first place.

But immediately his luck began to change. A young woman, Jane Wilde, he met on New Years Eve 1962 had taken a genuine interest in him, and the Cambridge Physics Department had assigned him to Dennis Sciama (b. 1926), one of the best-informed and most inspiring research advisers in the world of relativistic cosmology.

Once it is accepted that Stephen William Hawkings physical capabilities were severely limited by the tragic disease of ALS, a whole series of fortunate events seemed to have taken place in the early 1960s which enabled him to fulfil his destiny as one of the leading cosmologists of modern times.

First of all, for the profession he had chosen theoretical physics the only facility he absolutely needed was his brain, which was completely unaffected by his illness. He had met a helpful partner in Jane Wilde and been presented with a sympathetic thesis adviser, Sciama.

Soon he would meet Roger Penrose (b. 1931), a brilliant mathematician working on black holes, who would teach him radically new analytical tools in physics. Penrose would help him solve a research problem that would not only save his doctoral dissertation but also bring him directly into mainstream theoretical physics.

The help of these three people at such a critical time in Hawkings life is perhaps more than anyone can hope for.

He had another appointment with destiny at about the same time. A theory which had been developed almost fifty years earlier Einsteins general theory of relativity was only just being widely applied to practical problems in cosmology. It seems that predictions based on this theory were so bizarre that it had taken decades for it to be accepted. Now in the early 1960s, a golden age of research in cosmology based on general relativity was about to begin. Fate had waited for Stephen Hawking. The secretly ambitious though by then slightly crippled theoretical physicist was ready. He didnt know how long he had to live but he was certainly in the right place at the right time.

MAYBE HE WAS LUCKY.

Stephen Hawking is called a relativistic cosmologist. This means he studies the Universe as a whole (cosmologist) and uses mainly the theory of relativity (relativistic).

As Hawking has spent his entire career as a theoretical physicist from the early 1960s to the mid 1990s working with Einsteins general relativity, it might be a good idea to know what its about.

The General Theory of Relativity

Berlin, November 1915. Albert Einstein (1879-1955) had just completed his theory of general relativity, a mathematical structure in which curved space and warped time are used to describe gravitation. All modern cosmology began two years later, when Einstein published a second paper called Cosmological Considerations in which he applied his new theory to the entire Universe.

General relativity is difficult to master, but the relatively few people who understand the theory agree it is an elegant, even beautiful theory of gravitation.

Describing a set of equations as beautiful doesnt help much in understanding how Einsteins theory differs from that of Isaac Newton (1642-1727). But an example of how each of the two theories describes gravity in the same physical situation might do the trick.

Why does a, cosmologist have to study gravitation?

Cosmology is the study of the whole Universe and much of the subject is based on wide-sweeping hypotheses. Gravitation determines the large-scale structure of the Universe or, more simply, keeps the planets star and galaxies together. It is the most important concept for work in this field.

Until recently, the subject of cosmology was considered to be a pseudo-science reserved for retired emeritus professors. But in the last three decades, more or less coinciding with Hawkings career, two major developments have changed the subject dramatically.

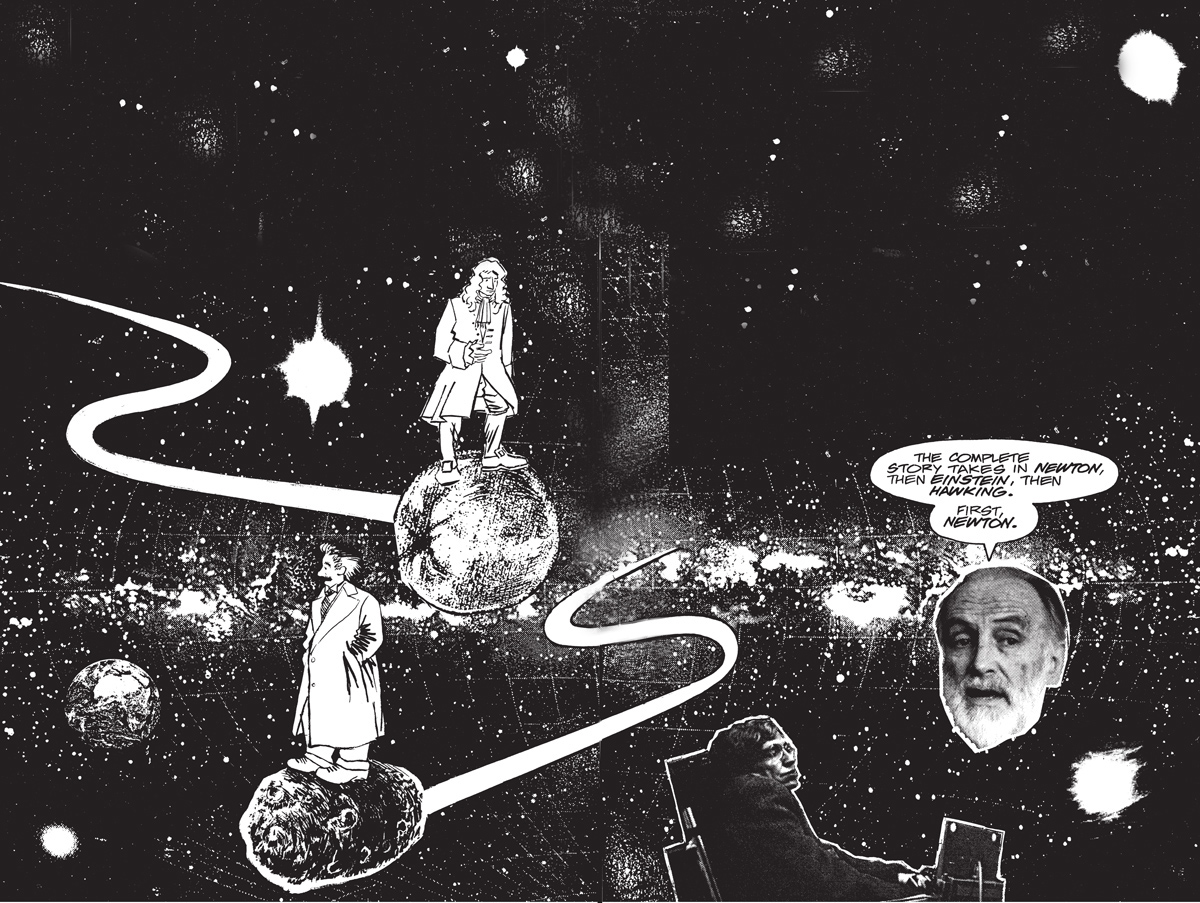

THE COMPLETE STORY TAKES IN NEWTON, THEN EINSTEIN, THEN HAWKING FIRST, NEWTON.

- First, major breakthroughs in observational astronomy reaching out to the most distant galaxies have made the Universe a laboratory to test cosmological models

- Second, Einsteins general relativity has been proven over and over again to be an accurate and reliable theory of gravitation throughout the entire Universe.

Remember, physics is a cumulative subject. New theories are built on previous ones, keeping the ideas that stand up to experimental test and discarding those that dont. Our final goal is to understand the contributions of Stephen Hawking who has taken Einsteins gravitation theory to its ultimate limit.

It is important to understand the notion of