Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Copyright 2023 by Thomas Hertog

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Bantam Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Bantam Books is a registered trademark and the B colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Illustration credits are located on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hertog, Thomas, author.

Title: On the origin of time : Stephen Hawkings final theory / Thomas Hertog.

Description: First edition. | New York : Bantam Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022035059 (print) | LCCN 2022035060 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593128442 (hardback) | ISBN 9780593128459 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593722626 (international)

Subjects: LCSH: Hawking, Stephen, 19422018. | Cosmology. | Universe.

Classification: LCC QB981 .H475 2023 (print) | LCC QB981 (ebook) | DDC 523.1/2dc23/eng20221021

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022035059

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022035060

Ebook ISBN9780593128459

randomhousebooks.com

Title-page image: ESA/Hubble & NASA, A. Newman, M. Akhshik, K. Whitaker

Book design by Simon M. Sullivan, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Ben Denzer

Cover images: Hubblesite/NASA (nebula), Getty Images (eyeball)

ep_prh_6.1_143034194_c0_r0

Contents

_143034194_

La question de lorigine cache lorigine de la question.

The question of the origin hides the origin of the question.

Franois Jacqmin

PREFACE

The door to Stephen Hawkings office was olive green, and, though it was right off of the bustling common room, Stephen liked it to be slightly open. I knocked and entered, feeling as though Id been transported into a timeless world of contemplation.

I found Stephen sitting quietly behind his desk, facing the entrance, with his head, too heavy to hold straight, leaning against a headrest on his wheelchair. He slowly raised his eyes and greeted me with a welcoming smile, as if he had been expecting me all along. His nurse offered me a seat next to him and I glanced at the computer on his desk. A screen saver scrolled perpetually across the screen: To boldly go where Star Trek fears to tread.

It was mid-June of 1998, and we were deep in the labyrinth of DAMTP, Cambridges renowned Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics. DAMTP was housed in a creaking Victorian building on the Old Press site on the banks of the river Cam, and for nearly three decades, this had been Stephens base camp, the nexus of his scientific endeavors. It was here that he, wheelchair bound and unable to lift even a finger, had passionately strived to bend the cosmos to his will.

Stephens colleague Neil Turok had told me the master wanted to see me. It was Turoks animated course, part of DAMTPs famous advanced math degree, that had recently kindled my interest in cosmology. Stephen had got wind, it seemed, that my exam results were excellent and wanted to see if Id make a good doctoral candidate under his wing.

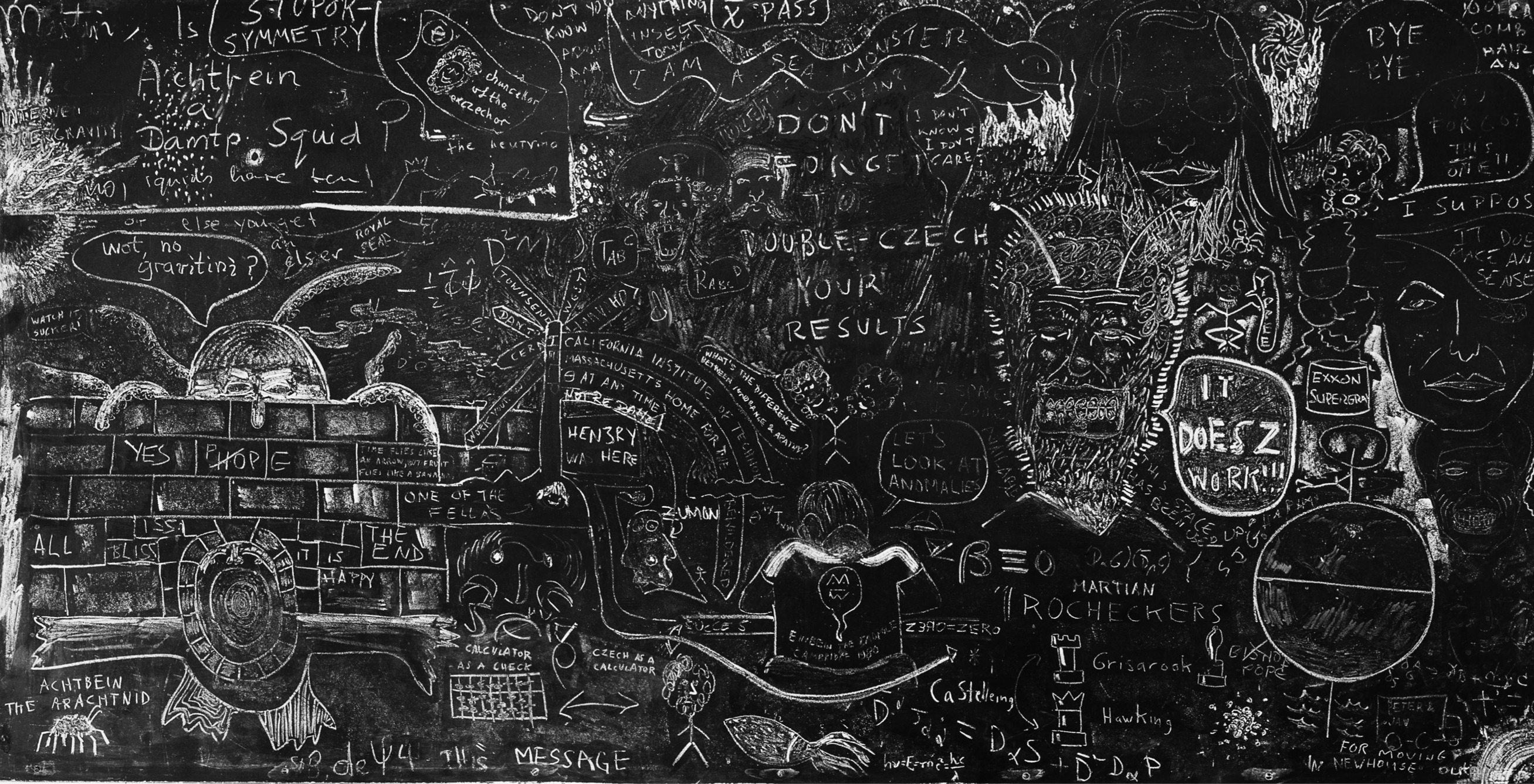

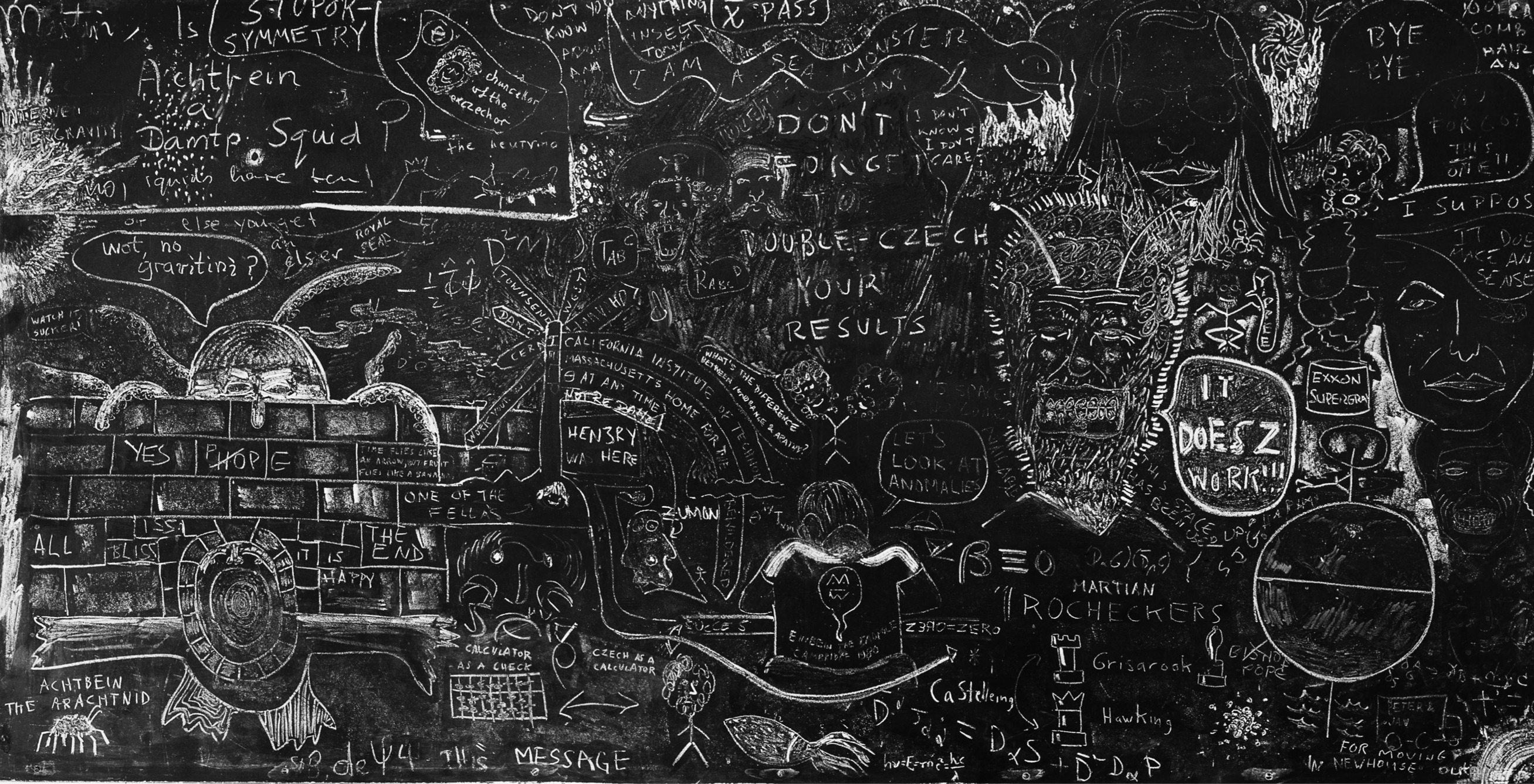

Stephens dusty old office stuffed with books and scientific papers felt cozy to me. It had high ceilings and a large window that, I would later find out, he kept open even on freezing cold winter days. On the wall next to the doorway was a picture of Marilyn Monroe; below it a framed and signed photograph of Hawking playing poker with Einstein and Newton on the holodeck of the Enterprise. Two blackboards filled with mathematical symbols occupied the wall to our right. One featured a recent calculation to do with Neil and Stephens latest theory of the origin of the universe but the drawings and formulas on the second one appeared to date from the early 1980s. Could they be his last handwritten scrawls?

Figure 1. This blackboard hung in Stephen Hawkings office at the University of Cambridge as a memento from a conference on supergravity he convened in June 1980. Filled with doodles, drawings, and equations, it is as much a work of art as a glimpse into the abstract universe of theoretical physicists. Hawking is drawn in the center near the bottom, with his back toward us. in the insert.)

A soft clicking broke the silence. Stephen had started talking. Having lost his natural voice in a tracheotomy following a bout of pneumonia more than a decade before, he now communicated through a disembodied computer voice. This was a slow, laborious process.

Mustering the last bit of force in his atrophied muscles, he exerted a feeble pressure on a clicking device, much like a computer mouse, which had been placed carefully in the palm of his right hand. The screen fitted to an arm of his wheelchair lit up, establishing a virtual lifeline between his mind and the outside world.

Stephen used a computer program called Equalizer that had a built-in database of words and a speech synthesizer. He appeared to navigate Equalizers electronic dictionary instinctively, pressing the clicker rhythmically as if it were dancing to his brain waves. A menu on the screen displayed a number of frequently used words and the letters of the alphabet. The programs database included theoretical physics jargon, and the program anticipated his next word choice, displaying five options in the bottom row of the menu. Unfortunately, word selection was based on an elementary search algorithm, which failed to distinguish between general conversation and theoretical physics, with sometimes hilarious results, from cosmic microwave risotto to extra sex dimensions.

Andrei claims appeared on the screen below the menu. I waited, in hushed expectation, fervently hoping that I would understand whatever followed. A minute or two later Stephen directed the cursor to the icon Speak in the upper left corner of the screen and said, in his electronic voice, Andrei claims there are infinitely many universes. This is outrageous.

There we had itStephens opening shot.

Andrei was the celebrated American-Russian cosmologist Andrei Linde, one of the founding fathers of the cosmological theory of inflation, proposed in the early 1980s. A refinement of the big bang theory, it postulates that the universe began with a brief burst of superfast expansioninflation. Linde later concocted an extravagant extension of his theory, in which inflation produced not one but many universes.

I used to think of the universe as all there is. But how much is that? In Lindes scheme, what we have been calling the universe would be only a sliver of a vastly larger multiverse. He envisaged the cosmos as an enormous swelling expanse of countless different universes lying far beyond one anothers horizons, like islands in an ever-inflating ocean. Cosmologists were in for a wild ride. Stephen, the most adventurous of them all, had taken note.

Why worry about other universes?