Contents

For Steve Byrne

Prologue

LOOKING BACK, I CAN SEE HOW MY WHOLE LIFE HAS LED TO THIS: a book about a book about anatomy and about the education of an anatomist, albeit an amateur one. Sigmund Freud was right, it turns out: Anatomy is destinyor mine, at least.

A bloom in a boulder crack, my fascination with human anatomy took root in the less-than-accommodating conditions of a strict Irish Catholic upbringing in the 1960s. You are made in Gods image, I remember being told by the nuns in catechism classes, which struck me as wonderful news; to cherish your body was to cherish the Creator. At the same time, though, the story of Adam and Eve made it frighteningly clear that the body is a shameful vessel for sin. Even today, while I no longer consider myself Catholic or even religious, the tale of their fall from innocence haunts me: God warning Adam, you shall die if you eat of the tree of knowledge, and then Evepoor, gullible Evesweet-talked by the snake, pulling an apple from the tree. I still just want to stop herNo!

Then the eyes of both were opened; and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together. Banishment from the garden was but one part of their sentence. You are dust, God tells them, and to dust you shall return.

The moral, simple enough for a child to grasp, is that when God says no, he really means no. But the story also conveys a more insidious notion: awareness of the body may lead to spiritual death.

To the eight-year-old me, fresh from making my first confession, Adam and Eve were especially effective in promoting the idea that nakedness went hand in hand with sin. And yet, making matters morally confusing, there were some naked people it was okay to look at, whose nakedness you were meant to take notice of, beginning, ironically enough, with Adam and Eve. Even in my childrens Bible, those two appeared as delectable as a couple of ripe Red Delicious apples. The most frequent naked body I saw while growing up, though, belonged to Jesus. In our house, crucifixes were as common as light fixtures. A small bronze one hung above my bed, and I prayed to it every night. But, in a curious design choice, as I think of it now, the largest crucifix was posted right outside the bathroom my five sisters and I shared. Jesus, as if clad in a towel rather than a loincloth, appeared to be waiting his turn for the shower. I can still recall every detail of that crucifix, a wooden one my dad had bought in Mexico. The body was carved with such care, so that legs and arms were finely muscled and veined and the torso made long and sinuous. His nakedness exposed every crucifixion wound and was crucial to reinforcing a central tenet of the church: The gash along his ribs was due to our sin. The trickle of blood down his forehead was our fault. Christs pain was meant to cause you the same. His death, we were never to forget, was for us.

Providing a ballast to the Irish Catholicism of my father was my mother. Mom had once been an aspiring painter in New York City before meeting Dad, and she was not Catholic. Only on the rarest occasions did Mom join us at church. I remember how, every year on Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent, when a thumb-press of ash was placed on your forehead as a reminder of your mortality, Moms unsmudged brow marked her as unlike my father and sisters and me. Dad would jokingly call her a heathen but, almost in the same breath, say earnestly to his six children, Moms a saintthats why she doesnt need to go to Mass.

To me, Mom represented the everyday, but also another, higher worlda world of artists; of passionate, driven people; a world I glimpsed in her little library of art books. Above the table where her sewing machine sat was a pinewood bookshelf that held histories of famous painters as well as exhibition catalogs from far-off places such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York. While the book Picassos Picassos only confused me, the thick tomes on Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Matisse introduced me to the sensual body as art. These books were full of nudes, not naked people, a distinction I began to understand as I edged toward puberty.

Lining the shelf on the opposite wall was our 1965 World Book encyclopedia, twenty-two volumes, straight-spined and orderly, like the cadets in a photo nearby: the 1949 graduating class of West Point, with Dad standing third from the left, front row. It was in World Book volume H that I got my first peek inside the human body. Between entries on hairstyling and hysterectomy, there was a spectacular anatomical illustration composed of ten bright transparent overlays. The body illustrated was male, although, in a nod to modesty, no genitalia were shown. To this day, I still recall the smell of the plastic sheets and the sticky sound they made when you turned each overlay. Sometimes I would run up to one of my sisters and flash Encyclopedia Man in her face, eliciting a guaranteed ick!!this form of teasing worked especially well on Julia, three years younger than me, and Shannon, two years olderbut we would then often sit down and look at the illustrations together, drawn into the illusion of a deep body adventure, as though we wore X-Ray Specs that actually worked. Paging from left to right performed a crude dissection, salmon-colored muscle giving way to the wet worms of viscera giving way to less and less until, finally, on the last transparency, only the unadorned skeleton remained.

My two best friends dads were both doctors, one a G.P., one a dermatologist. Their family bookshelves held volumes that I would never be able to find even at the Spokane Public Library: old medical textbooks. Kept on topmost shelves, they were meant to be out of reach, out of sight, which is of course exactly why I would urge Chris or Andy to fetch them. What I will never forget is the deformities and disfigurements pictured: photos, as artless as mug shots, of elephantiasis, leprosy, gargantuan tumors, and other conditions that made the body seductively grotesque.

Though I confided this to neither Chris nor Andy nor any of my sisters, I dreamed of becoming a doctor one day. But whether because I did so poorly in high school biology and chemistry or because I did so well in English and writing classes, I eventually shelved the idea of a medical career. Still, my interest in the workings of the body remained; indeed, I think it intensified in direct proportion to my burgeoning interest in sex. But by the time I was actually having sex, after moving to San Francisco in the early 1980s, the body had turned virtually overnight into something to fear, a vessel not for mortal sin but for a deadly virus. That was when I bought my first copy of Grays Anatomy.

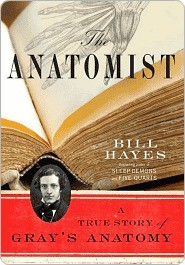

I got it for the pictures: hundreds of drawings of lean muscle, bones, and organs, each meticulously rendered and labeled as if it were a rare entomology specimen. Lying on a bookstore table, the thick volumes cover image had first drawn me in: a profile of a man whose face is intact but whose neck is not, to put it mildly. The skin from the chin to the collarbone is missing, revealing strips of muscle and a tangle of blood vessels. As gruesome as it was, I found the image incongruously beautiful. The young man wore such a serene expression, and there was something so intimate in his posethe way his head was gently turned to expose every detail, as if in invitation:

Next page