Published 2015 by Humanity Books, an imprint of Prometheus Books

The Anatomist, the Barber-Surgeon, and the King: How the Accidental Death of Henry II of France Changed the World. Copyright 2015 by Seymour I. Schwartz. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

Cover design by Nicole Sommer-Lecht

Inquiries should be addressed to

Humanity Books

59 John Glenn Drive

Amherst, New York 14228

VOICE: 716-691-0133

FAX: 716-691-0137

WWW.PROMETHEUSBOOKS.COM

19 18 17 16 15 5 4 3 2 1

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Schwartz, Seymour I., 1928- , author.

The anatomist, the barber-surgeon, and the king : how the accidental death of Henry II of France changed the world / by Seymour I. Schwartz.

p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-63388-034-4 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-63388-035-1 (ebook)

I. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Henry II, King of France, 1519-1559. 2. Vesalius, Andreas, 1514-1564. 3. Par, Ambroise, 1510?-1590. 4. History of MedicineFrance. 5. Anatomy--history--France. 6. Famous Persons--France. 7. General Surgery--history--France. 8. History, 16th Century--France. 9. Politics--France. WZ 70 GF7]

R504

610.94409031--dc23

2015000294

Printed in the United States of America

Vidi---Legi---Scripsi

INTRODUCTION

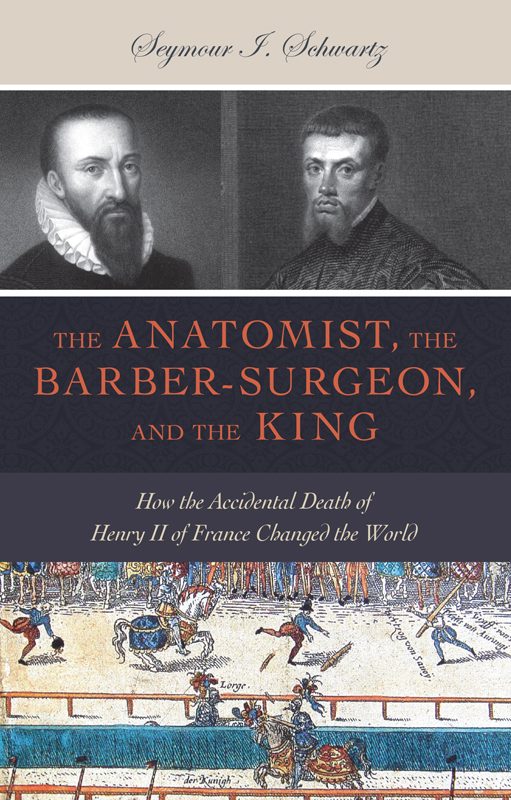

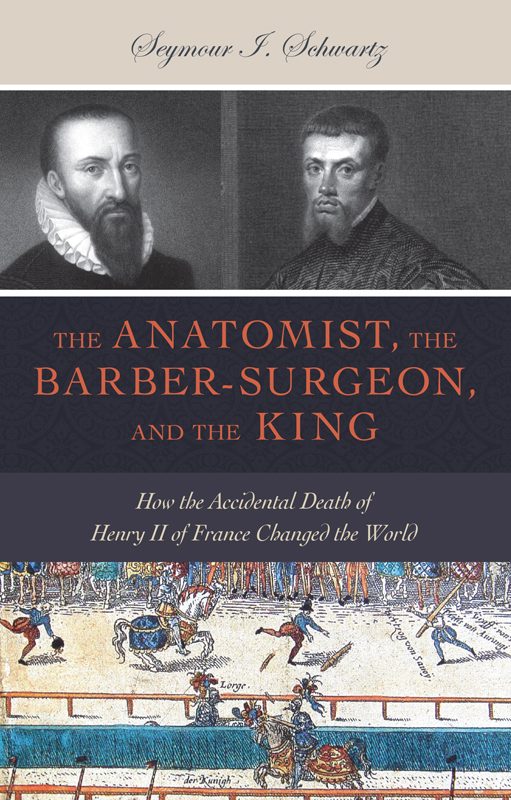

The chance viewing of a picture that was printed almost four and a half centuries ago provided the stimulus for this work. The woodcut is, of itself, significant because it represents one of the earliest examples of printed graphic journalism, the ancient forerunner of modern photojournalism. The specific print, La mort du roy Henry deuxieme aux tournelles Paris, le x. Julliet, 1559 [The death of King Henry II at the Tournelles at Paris, July 10, 1559], chronicled a transformative event. A descriptive narrative offered a definition of the individuals who were represented on the print, including the two most notable contributors to the renaissance of medicine standing side by side in consultation. Andreas Vesalius, the father of modern anatomy, was within arms length of Ambroise Par, the great surgical innovator. The two physicians, whose contributions advanced medicine and surgery and who had previously attended the wounded and sick soldiers of opposing armies, were brought together to attend the dying king of France.

The early print triggered several diverse pathways of investigation. One path focused on the lives and contributions of the two depicted physicians in order to determine the factors that led to their eminence and the call for their specific consultation related to the medical management of one of the most powerful figures among European royalty. Although there had been a previously asserted intellectual bond between the two medical innovators, in that Ambroise Par had formally credited Andreas Vesaliuss modernization of anatomy as indispensable to the formers transformation of surgery, the two achieved their respective reputations and renown despite distinctly different starting points. Similarly, the paths they took to achieve their individual recognition and those they would follow after their roles in the care of the dying French king were decidedly different.

Another distinct pathway of inquiry, unrelated to medicine yet also emanating from the ancient woodcut, focused on the central dying figure, Henry II, king of France. At the time of the graphically chronicled event, Henry II was effectively the reigning head of the House of Valois, one of the two royal dynasties that dominated sixteenth-century Europe. The House of Valois was opposed throughout that period by the Habsburgs, who were led sequentially by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and his son, King Philip II of Spain.

Henry IIs deathbed scene was the consequence of an improbable accident during a joust, a competitive demonstration that was characteristically performed at important occasions. The devastating accident interrupted the festivities of two related weddings, one of which was directed at relieving the polarization between Europes two competing dynasties. And to add to the improbability associated with the accident, which resulted in the untimely demise of the French king, the death had been predicted, with extraordinary specificity, by two of Europes most notable contemporary prognosticators well in advance of its occurrence. Also, just before the accident took place, more warnings and admonitions, accompanied by pleas to abort the joust, went unheeded.

The death of the central royal figure in the graphic journalistic print marked a watershed for European history in the sixteenth century. The period before the death of Henry II was replete with shifts of political power and dominance, wars, and changes in possession of kingdoms. That time span also witnessed the birth and early rise of the religious movement known as Protestantism, which transformed Europe and the world.

After the death of the king, the power of France was immediately and persistently weakened. Henrys three sons, who sequentially occupied the throne, were incapable of providing the required leadership or stature. The immediate successor, Francis II, was a sickly fifteen year old, who died after a reign of less than fifteen months. This led to the ascension of Francis IIs younger brother, who became Charles IX at the age of ten. He reigned, as a youth, until he died at the age of twenty-four. This resulted in the coronation of the third of Henry IIs sons, an effeminate twenty-two year old, noted for his laxity and penchant for frivolity, as Henry III. He would occupy the throne during a turbulent era until he was murdered in 1589, bringing to an end the rule of the House of Valois.

The void left by the death of Henry II, enhanced by the weaknesses of his successors, was filled by the expansive political presence of Henry IIs wife, Catherine de Medici. During the thirty years between the death of Henry II and the time of Catherines death, she loomed as the dominant member of the French royalty, and guided the policy of the nation.

The second half of the sixteenth century in France and throughout Europe was dominated by the spread of Protestantism and consequent political unrest, which would impact directly on the lives of the two medical personalities, whose presence on the ancient print stimulated my initial inquiry.

There is also an intriguing recurrence of the number two throughout this history. The two most notable medical personalities of the Renaissance were brought together to care for Henry II, the second son of the monarch he succeeded. The mortal blow, which Henry II sustained, occurred during the second time that the same two opponents met during the joust. The joust took place in celebration of two marriages, the more prestigious involving Phillip II of Spain as the groom. It was hoped that the marriage would reduce the tensions between the two dominant European dynasties. The tragedy was predicted by two notable prognosticators. The death of Henry II was a watershed that took place at a time that essentially divided the century into

Next page