Contents

Also by Lauren Johnson

FICTION

The Arrow of Sherwood

NON-FICTION

So Great a Prince: England and

the Accession of Henry VIII

THE SHADOW KING

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2019 by Lauren Johnson

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition May 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher,

except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review

in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this

book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or

by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or

other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN: 978-1-64313-128-3

ISBN: 978-1-64313-165-8 (eBook)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

For Mum, Dad & Joe

for everything

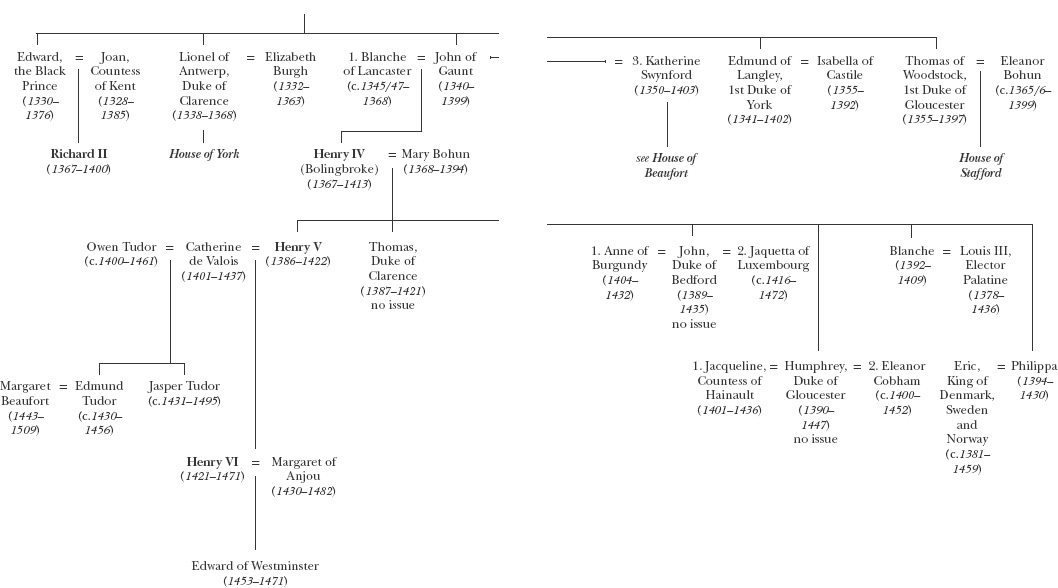

The fifteenth century was an age of woefully unimaginative forenames and complex titles, so in naming the key players in Henrys life I have striven for clarity, occasionally at the expense of strict historical accuracy (e.g. John Beaufort rather than John Beaufort, third earl of Somerset / first duke of Somerset). For those of non-English origin I have used their original names instead of anglicized versions (e.g. Franois not Francis), with two notable exceptions: Joan of Arc and Margaret of Anjou. Since both are well-known historical figures in British history, for clarity I have used the anglicized version of their names.

Although the fifteenth-century calendar dated the new year from Lady Day (25 March) or, in the case of civic records, sometimes from the date of a mayors election, I have followed modern convention and dated all years from 1 January.

Both English and French currency in this period were divided into denominations, sometimes labyrinthine in their complexity. The key denominations are given below:

English

12 pennies = 1 shilling

20 shillings = 1 pound

1 mark = two-thirds of a pound (13s 4d or 160 pence)

French

12 deniers = 1 sol

20 sols = 1 livre tournois

Distances between two locations are based on Google Maps walking directions.

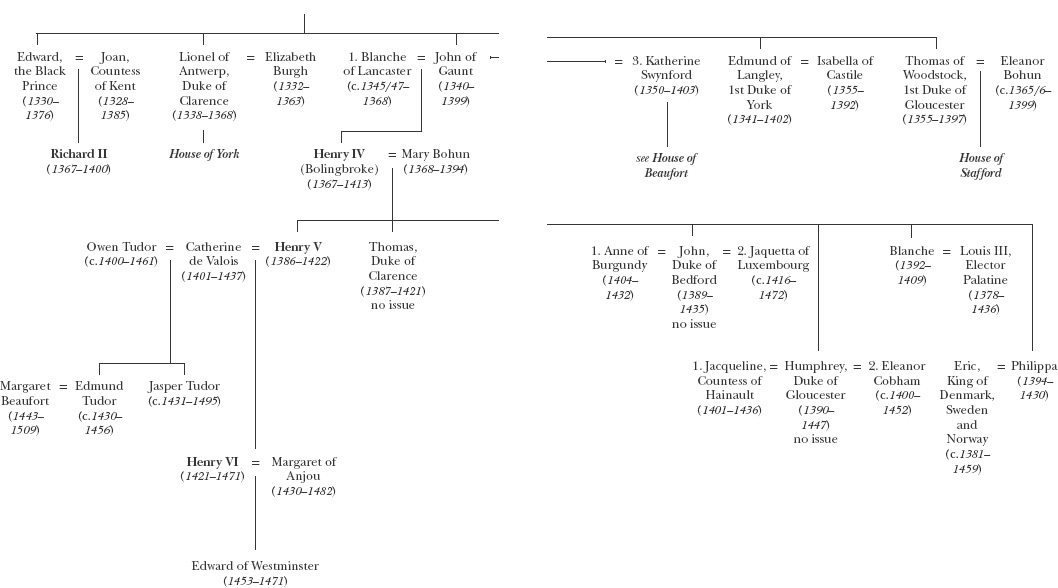

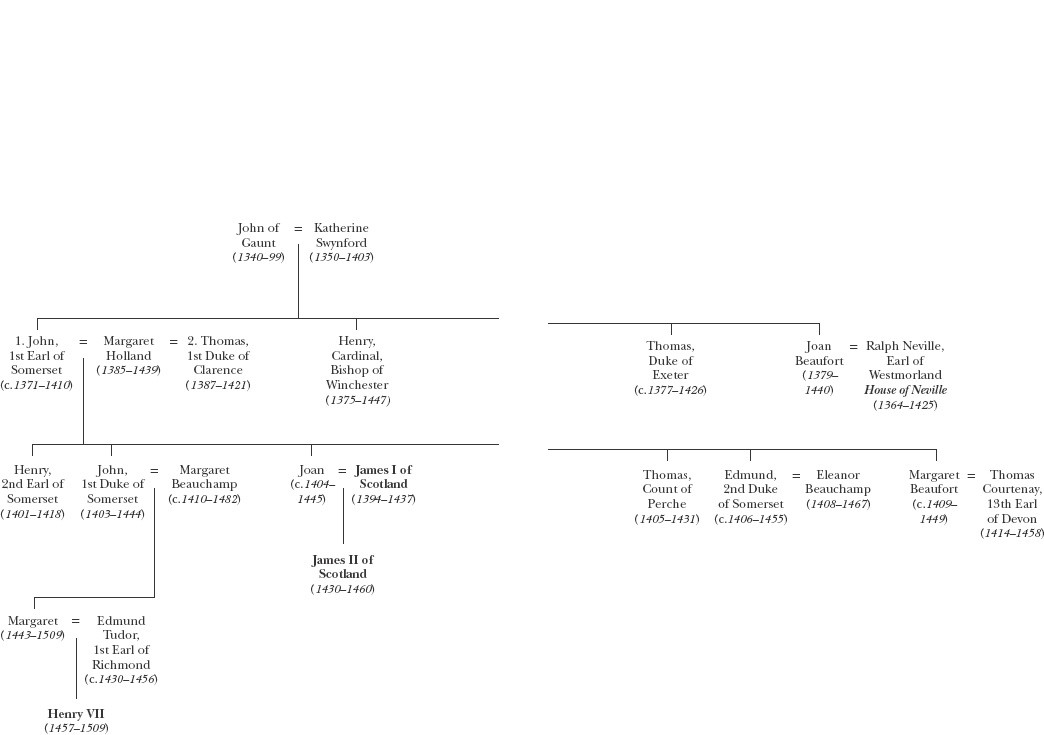

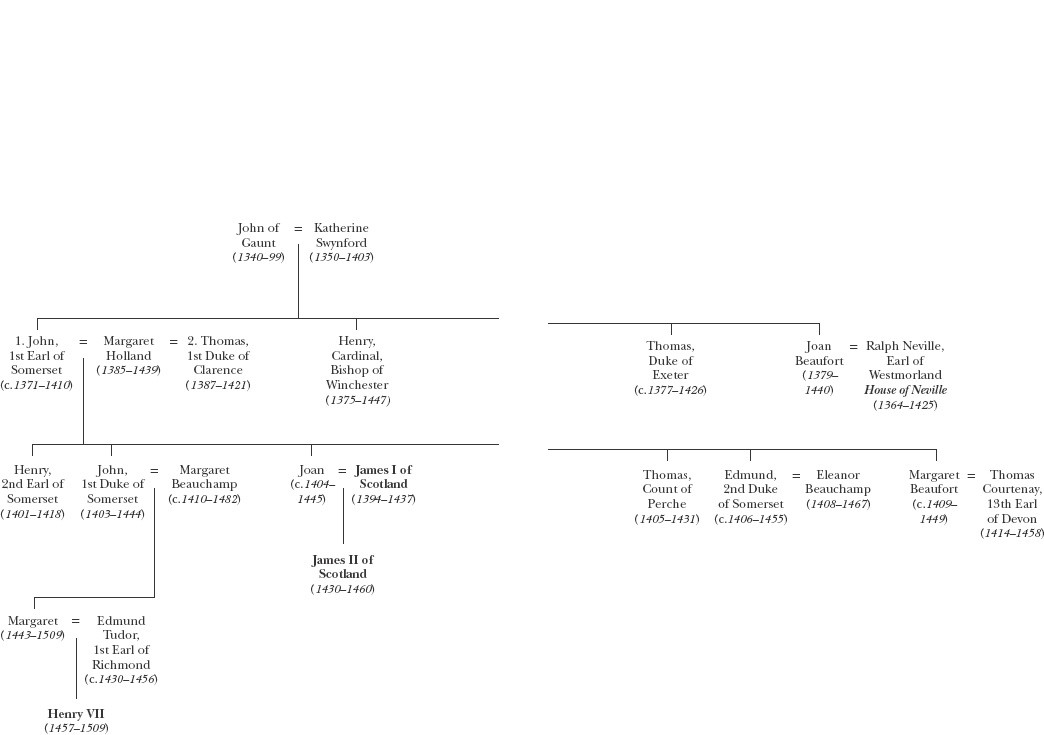

House of Beaufort

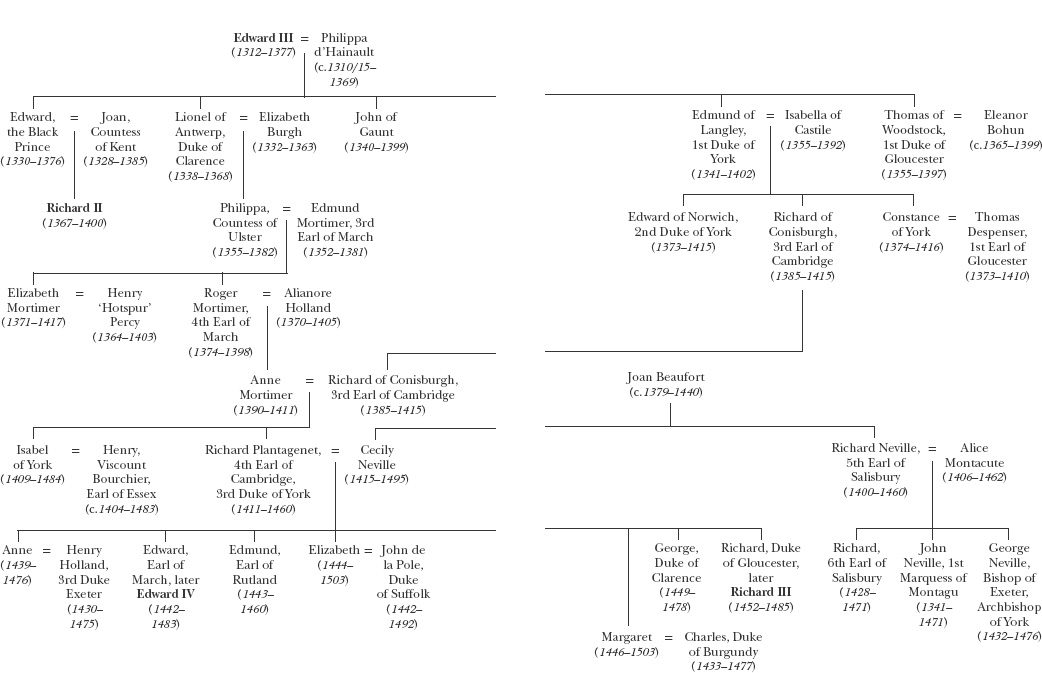

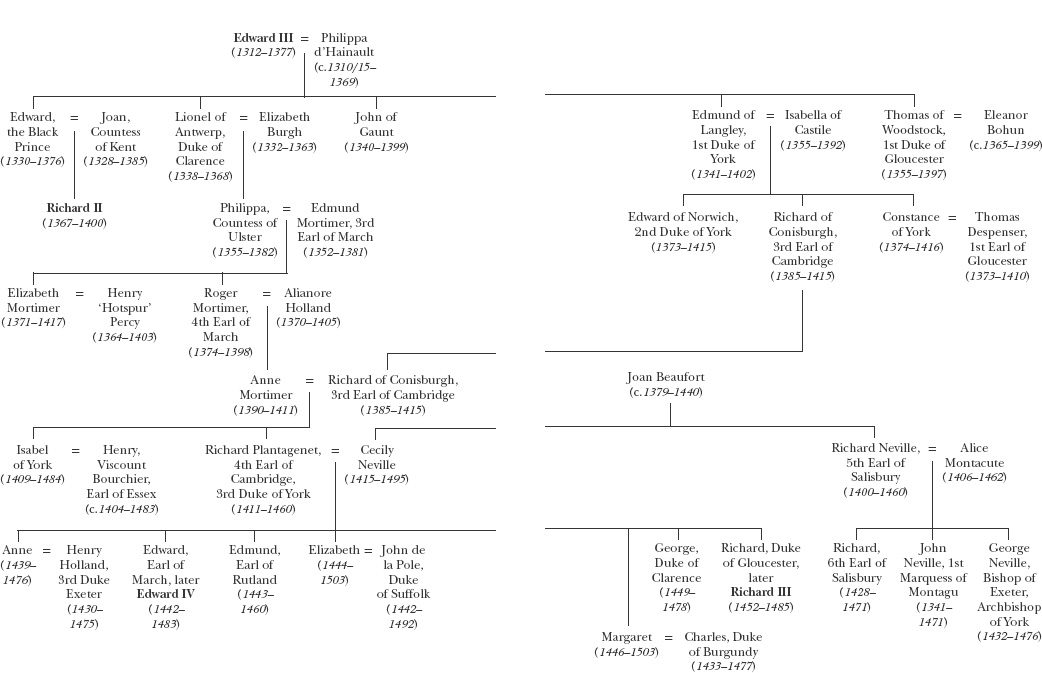

House of York

London

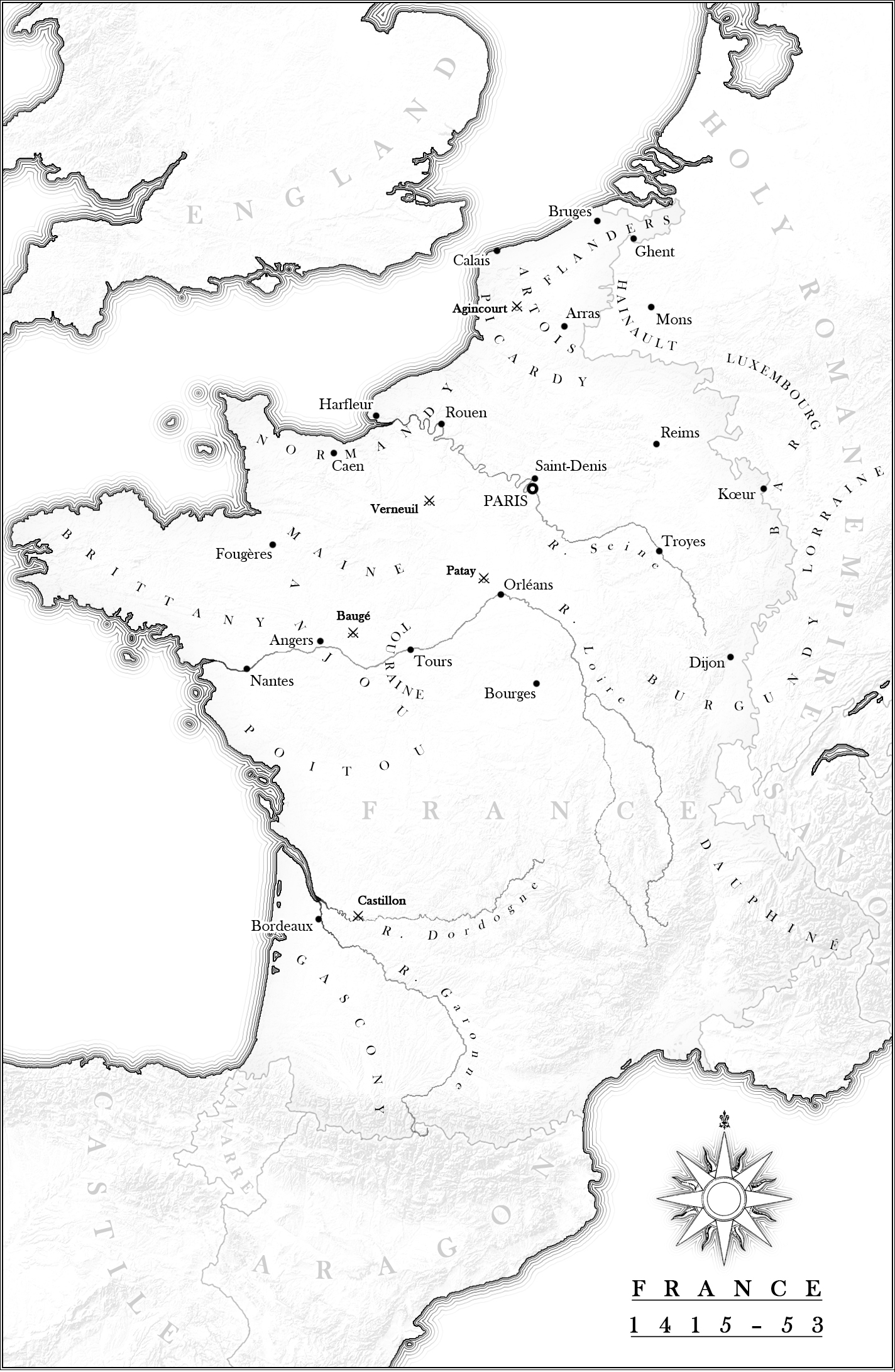

5 November 1422

T he funeral procession reached London as the church bells struck one. Throughout its journey from France, this was the sound that had accompanied the body of the dead king: a distant, dull tolling that rose to welcome him into each new settlement where his cortege paused, and underneath it the familiar rhythmic chanting of the Office of the Dead. From the castle of Bois de Vincennes, southeast of Paris, the mournful incantations of monks had echoed across the contested territories of the king of France, into the duchy of Normandy, over the sea to Kent and all the way to the capital of England itself.

The cortege took a route that had been well known to the king in life. He had made such ceremonial entries into London when he was crowned, when he returned as a conquering hero of the wars with France and brought the city its new queen as hostage to peace. But now the subjects who had heralded victory with drunken shouts and triumphant music watched the procession pass in eerie silence. The only sounds were bells, chanting, and the rough footfall of those who marched with the dead sovereign.

The kings place was easy to find in this pageant of grief: his coffin lay swathed in black velvet and golden silk on a carriage pulled by five horses. All around him the banners of his patron saints fluttered: St Edward of England, St George, St Edmund, the Virgin Mary and the Holy Trinity. As it processed to Westminster Abbey for burial the following day, his coffin would be topped with a life-size image of the king himself, crafted from leather that had been boiled and then painted. The face would still look young, for the king had only been thirty-six when he died. Instead of the armour of a warrior, so familiar to those who had known him in life, the mannequin would wear all the regalia of monarchy: velvet robes and crown, a golden orb and sceptre in his painted hands.

Around the dead king flocked the warrior lords who had accompanied him to France, mounted on horses draped in black. In stark contrast, the figures who walked before the funeral car wore newly made white gowns, torches blazing in their hands. Despite their lustre, these men and women were poor, their clothes a charitable donation to keep once the funeral was over. Between these two extremes of wealth and rank came the religious and the guilds. The king had been famed for his piety in life, so it was only right that everywhere the eye turned a priest or bishop could be seen, a mitred abbot or poor friar. And, since London was at heart a merchant city, the thirty-one trade guilds who dealt in everything from silk to pins had the honour of accompanying the king on his final journey through their streets. So vast was the procession that, when the kings body reached the doors of St Pauls Cathedral to rest overnight, the mourners at its rear, including Queen Catherine, had still not crossed London Bridge, 2 miles (3 km) behind. Catherine was barely in her twenties, only two years married, a new mother and now a widow.

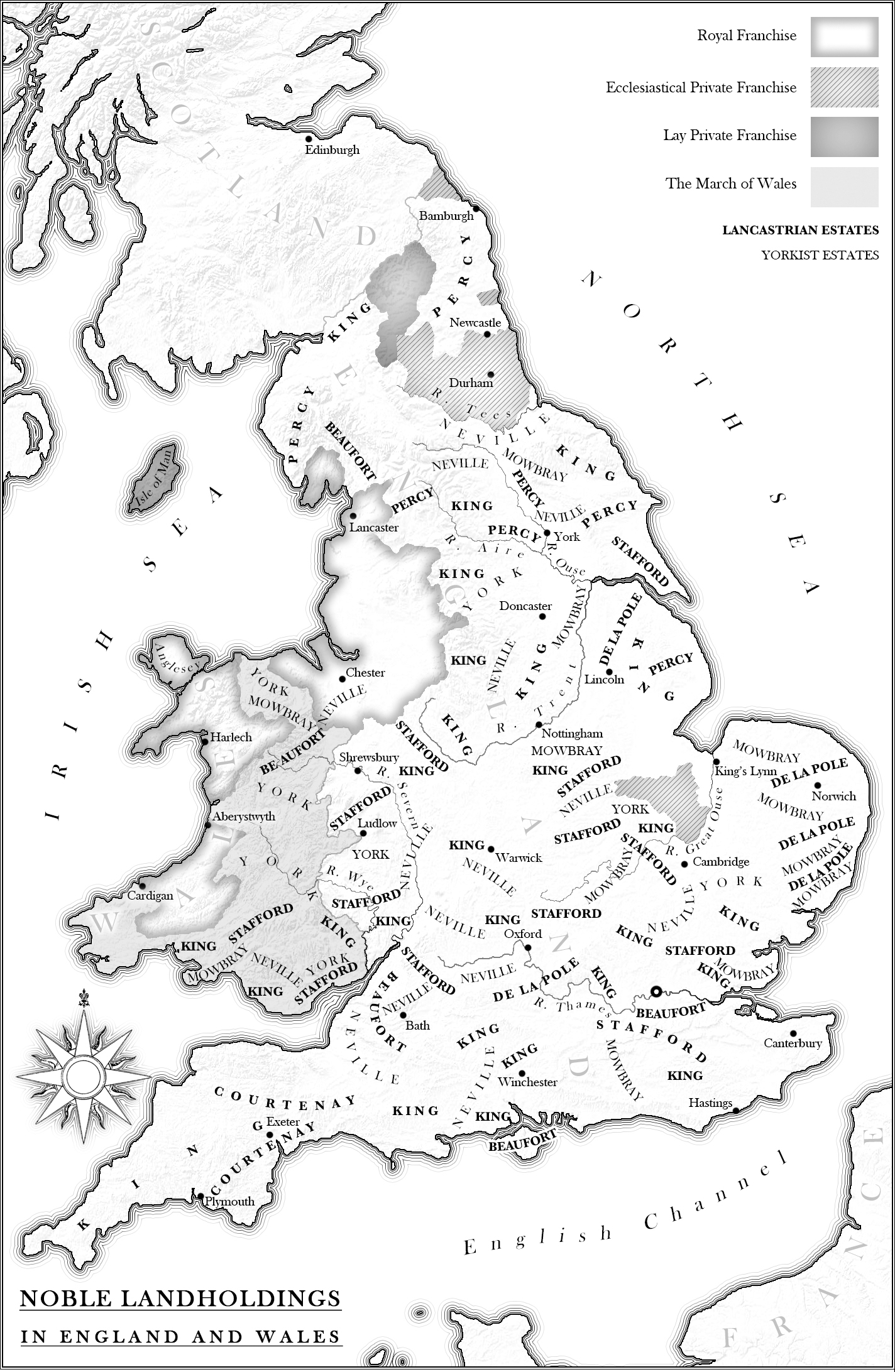

Within the 2-mile (3 km) radius encircling the dead king, all the peoples of England were represented, from queen to commoner. Royal counsellors, pages in training, silkwomen, paupers, foreign-born merchants, sailors, priests. But one person, as custom dictated, was absent from this vast funeral procession: the new king who had inherited his fathers realm. His reign had begun at the moment of the late kings death and every single person bowing their heads before the funeral car was now his subject. His lands stretched far beyond London, beyond the shores even of England and Wales. Like his ancestors, he claimed lordship over the duchies of Normandy and Gascony. For the first time in history, he was not merely rightful king of England, but king of France as well. He was now King Henry VI. And he was not yet one year old.

Fifty years later, in May 1471, the city of London was again the scene of a royal funeral procession. But this one was not carried out with the elaborate ritual of a reigning monarch. Soldiers surrounded the bier, bearing halberds instead of torches, as it made its journey from the Tower of London through the cramped and sombre streets to St Pauls Cathedral. There had been no time to make a funeral effigy indeed, the corpse was barely cold, death having taken place a matter of hours before, around midnight, within the Tower walls. Though the body was embalmed with wax and oil, and wrapped in fine linens, the dead mans long face was left exposed, its small, puckered lips and wide-set gaze familiar to the citizens of London. Curious eyes peered through the defensive ring of soldiers to catch a glimpse of the man as he passed. When it finally reached the cathedral, the body was set up on the pavement near the altar. Now bystanders were able to stare with impunity at the corpse of the king. Ominously, as it lay in the holy sanctuary of the cathedral, the body was seen to bleed afresh. For two days the corpse was displayed in this manner time enough to demonstrate, definitively, that this mans life was over. That the reign of Henry VI had come to an end.