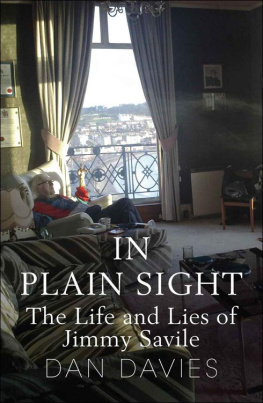

Dan Davies

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Quercus Editions Ltd

55 Baker Street

Seventh Floor, South Block

London

W1U 8EW

Copyright 2014 Dan Davies

The moral right of Dan Davies to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders of material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make restitution at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HB ISBN 978 1 78206 743 6

TPB ISBN 978 1 78206 744 3

EBOOK ISBN 978 1 78206 745 0

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Text designed and typeset by Ed Pickford

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

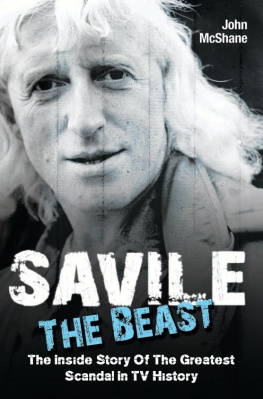

Picture credits (page references refer to print addition): ,

Mirrorpix; , Stanley Franklin/The Sun/News Syndication;

You can find this and many other great books at:

www.quercusbooks.co.uk

Contents

Guide

Page List

PART ONE

1. APOCALYPSE NOW THEN

S hortly before midnight, on a hill overlooking the North Yorkshire seaside town of Scarborough, the wrought-iron gates of Woodlands Cemetery were locked shut. Police officers took up position outside, while beyond, in the darkness and at the highest point of the burial ground, undertaker Robert Morphet and his men removed tools from their truck. Little was said as portable floodlights were assembled and attached to the generator they had brought with them from the Bradford headquarters of Joseph A. Hey & Sons, funeral directors.

The plan had been to arrive early the next morning but public and media interest was so great that Morphet had decided to discuss arrangements again with Scarborough Council. It was agreed to get the job completed as quickly as possible; in the dead of night, safe from prying eyes, telescopic lenses and those with possible vengeance on their minds.

The mood was sombre as the men set about their task with hammers, chisels, wedges, long bars and drills. Removing a six-foot wide, four-foot high triple headstone in black, polished granite was hard, physical and, in this case, demoralising work. For the headstone had taken Robert Morphet and his men eight months to complete, being inscribed both front and back with pictures of the man buried beneath, poems written by his friends, a short biography, a list of charities hed supported and an epitaph in flowing script along the base: It was good while it lasted.

Three separate slabs of granite, a base and fourteen hundred letters in total, each one finished in gold; Joseph A. Hey & Sons bill was in excess of 4,000. The headstone had been fixed to its concrete foundation stone only three weeks before.

The placing of the headstone, which was wide enough to cover three plots, should have been the concluding act in the biggest funeral ever arranged in the 130-year history of the firm. It had been a national funeral, a celebration of a remarkable life that had drawn crowds to the streets and been reported extensively in news bulletins and papers across Britain.

Morphet had told reporters that he considered it an honour when his firm was contacted soon after Saturday, 29 October 2011, when the body of an 84-year-old man had been discovered by the caretaker of a block of flats bordering Roundhay Park in Leeds. The man had been found lying in bed. There was a smile on his face and his fingers were crossed. The police confirmed there were no suspicious circumstances; he was old and had been unwell for some time. The last two months of his life had seen him cut short a round-Britain cruise through illness, and hed been in and out of hospital. Morphet considered it an honour because he knew of the man; the whole country did.

Reaction to the news of his death had been widespread. On Twitter, comedian Ricky Gervais hailed the deceased as a proper British eccentric, while author and newspaper columnist Tony Parsons described him as a sort of Wolfman Jack for Woolworths. BBC Radio and TV presenter Nicky Campbell went further, saying he was so unique, a character so extraordinary, a personality so fascinating yet impenetrable. You could not have made him up.

The following morning, his familiar face dominated the front pages of almost every Sunday newspaper in the land, while on the inside pages the great and good lined up to pay their respects. A spokesman for Prince Charles, who he had mentored and served as a trusted confidant, said he was saddened by the loss. Louis Theroux, maker of a memorable film twelve years earlier, described him as a hero. BBC Director General Mark Thompson said, Like millions of viewers and listeners we shall miss him greatly.

Even I was interviewed. The Mail on Sunday asked me to sum up his character and share a few stories from the times I had spent with him over the previous seven years.

Reporters called up former colleagues from his long career in radio to add their voices to the growing chorus. Curiously, none professed to have any great insight. David Hamilton talked of a very remote figure that didnt mingle much. Tony Blackburn suggested he was lonely and didnt have many friends. Dave Lee Travis, who had known him for close on fifty years, revealed in all that time theyd never had a meaningful chat. He kept himself to himself and put a shield up, said Travis. Broadcaster Stuart Hall told BBC Radio Five Live that he was unique but a loner.

As a child, Robert Morphet had written to the man whose funeral he was about to arrange. It was at a time when he was a huge national star, possibly Britains biggest, famous for his charity work and for hosting a hit television show that made childrens dreams come true. The young Robert Morphet had written in asking to become an undertaker for the day. Like the thousands of other British children who wrote letters in the course of the shows 19-year run, he had not received a reply. His wish had come true anyway.

Decades on, the funeral director acted on the instructions from the dead mans family and arranged for the body to be dressed in a favourite tracksuit fashioned from Lochaber tartan, a white T-shirt bearing the emblem of the Red Arrows, running shorts, socks and trainers. An honorary Marine Commando Green Beret was placed in one hand and his mothers silver rosary in the other; his Marine Commando medal was hung around his neck. Once dressed, the body was placed in an American-style coffin made of 18-gauge galvanised steel and finished in brushed gold satin, along with a single cigar and a small bottle of whisky.

For the first day of the funeral proceedings, the gold coffin was driven to a hotel in the centre of Leeds. There, in the foyer, it was placed carefully on a plinth draped in gold-tasselled blue velvet and adorned with cascades of white roses. When the doors of the hotel opened the next morning, people were already queuing outside to pay their final respects. Thousands more followed over the course of the day. I was among them.

Next page