NIKOS NATURE

Nikos Nature

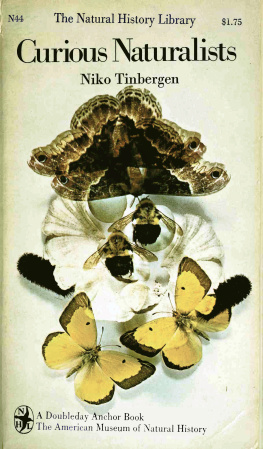

The Life of Niko Tinbergen

and his Science of Animal Behaviour

Hans Kruuk

With drawings and photographs by Niko Tinbergen

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai

Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul

Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi

So Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Oxford University Press, 2003

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2003

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

ISBN 0-19-851558-8

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset in Bembo

by Footnote Graphics Limited, Warminster, Wilts

Printed in Great Britain by

TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

To Jaap, Catrina, Dirk, Janet, and Gerry

Preface

Over the autumnal reds and yellows of dwarf shrubs I was looking at an overwhelming backdrop of glacier. Snow buntings came close, there was a lake with white-fronted geese, and a reindeer disappeared over the hillside. There were no people within many miles. Greenland is magnificent, gigantic, and awesome.

Seventy years earlier Niko and Lies Tinbergen had lived there, for a year. The grandeur of the country, and the Inuit views of life deeply affected Niko, scientist and naturalist. Greenland showed him what wilderness really was, and made him realize that he was a hunter at heart. The Inuit people, closer to nature than he was, made him view animals as objects, as machines, which are part of their environment, not separated from it. Nikos later ability to study animals as machines that had evolved in their own context and environment was vital for his development of the study of animal behaviour, ethology.

Experiments with free-living, wild birds, without disturbing them, were one of Nikos innovations which now seem commonplace. At the time when he began this, however, in the 1930s and 1940s, the idea rocked the world of animal behaviour studies. It was one of his simple approaches that built up a new branch of science, for which many years later he would be rewarded with the Nobel Prize.

Some forty years after I started as one of Nikos students, studying gulls in the dunes of north-west England, I met Marian Dawkins, Professor of Animal Behaviour, on the stairs in the Zoology Department in Oxford. She was also one of Nikos disciples, and we exchanged some reminiscence of the good old days. Isnt it sad, she said, looking at me, that no-one has ever written a biography of him?

The story of Niko Tinbergen is a fascinating one. He grew up in Holland, as a fanatic naturalist from his earliest years onwards, and as an athlete. He came from a highly motivated intellectual background: his eldest brother was to receive a Nobel Prize before Niko didand two in one family is still a record. There was his magical year in Greenland, his period as a hostage of the German occupation of Holland in the Second World War, his emigration to England. And there was his extraordinary friendship with Konrad Lorenz, which led to the establishment of ethology.

To Nikos enthusiastic group of students in Oxford he was The Maestro, who wrote the book that established ethology as a science: The study of instinct. He also wrote many others, made prize-winning films, and his bird photography and drawings were legendary. For scientists, Nikos main contribution lay in his clear logic, and in the simple questions he asked about animal behaviour. It was this that enabled him to design the beautiful field experiments, with animals in their own environment, and it was this that put ethology firmly in place as one aspect of biology. Those of us who worked with Niko watched the birth of a science, and later its absorption into other sciences. All of us remembered ourselves spellbound by his teaching: he was an arch-communicator.

There were several arguments that made me realize that I was probably the obvious person to write Nikos story. Most important, perhaps, was that I had known him well, and Niko was a friend and a mentor to me. Of course this could pose problems of one-sided reporting, as I am indebted to him. However, objectivity is what Niko always wanted himself, and he would insist on being treated without favours. I think that just as, in previous books, I have written objective descriptions of behaviour of animals I love, I can also be objective about the life of a person I was close to, now many years ago. Moreover, in this biography I present not just my own insights, but especially those of others, and I have tried to assess Nikos contribution against general scientific standards.

There were also other circumstances which put me in a favourable position to write about Niko. Because I am Dutch, the language of sources presented no difficulties. Like Niko I emigrated from Holland to Britain, and I can appreciate some of the problems, perceptions, and emotions involved. I can look back at the Netherlands and see some of the distinctive characteristics of its people, in a way that would be more difficult for either a Dutch person who does not have an outside vantage point, or for someone not Dutch. This also added interest for me to the process of writing the biography, as I saw some of my own history and emotions unfolding in Nikos transition across the North Sea. Finally, and perhaps at least as important as any of the other reasons, was that I am a naturalist in the mould of Niko, not with his abilities as an observer and scientist, but equally absorbed by birds, insects, and mammals anywhere in the world. I think I understand that part of him.

Many people have helped me tremendously, and I am, as someone who had never written a biography before, deeply grateful for their confidence in me. There is a slight feeling of guilt, because much of the detail I learnt from people has not been expressed in this book. It has nevertheless been highly important to me, as it provided vital background. I have had to select what I thought was most relevant, and leave out many events, as well as people who have played roles in the story. I take full responsibility for such omissions. I admire the forbearance of the Tinbergen children, who tolerated my probing into sensitive aspects of their parents lives without complaints, and who corrected many false impressions. Where their recollections disagreed, it was me who chose between them.

Next page