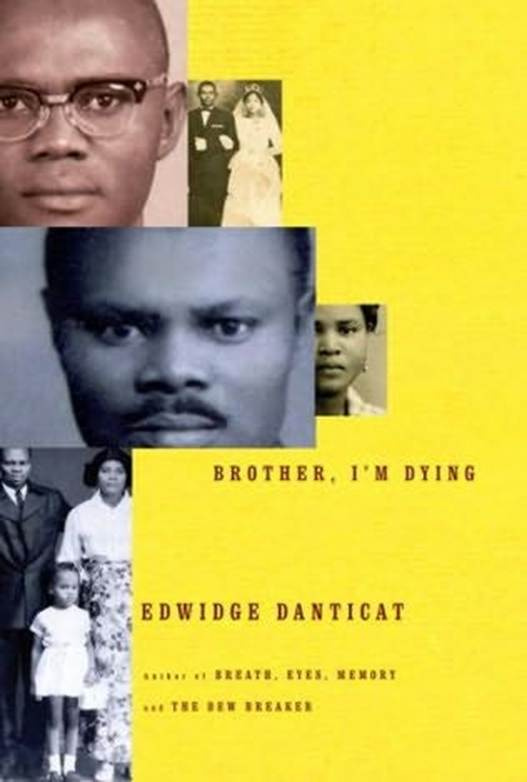

Edwidge Danticat

Brother, I'm Dying

Copyright 2007 by Edwidge Danticat

For the next generation of cats:

Nadira, Ezekiel,

Zora, Timothy

and Mira

To begin with death. To work my way back into life,

and then, finally, to return to death.

Or else: the vanity of trying to say anything about anyone.

PAUL AUSTER,

The Invention of Solitude

PART ONE. HE IS MY BROTHER

This is how you can show your love to me:

Everywhere we go, say of me, He is my brother.

GENESIS 20:13

Have You Enjoyed Your Life?

I found out I was pregnant the same day that my fathers rapid weight loss and chronic shortness of breath were positively diagnosed as end-stage pulmonary fibrosis.

It was a hot morning in early July 2004. I took a six thirty a.m. flight from Miami to accompany my father on a visit to a pulmonologist at Brooklyns Coney Island Hospital that afternoon. Id planned to catch up on my sleep during the flight, but cramping in my lower abdomen kept me awake.

I interpreted the cramps as a sign of worry for my father. In the past few months his breathing had grown labored and loud and hed been hospitalized three times. During his most recent hospital stay, he had been referred to a pulmonologist, whod since performed a new battery of tests.

My father picked me up at the airport at nine a.m. We hadnt seen each other in a month. Two years before, in August 2002, I had married and moved to Miami, where my then fianc was living. Fearing my fathers disapproval, I hadnt announced my intention to leave New York until a month before the wedding when my father summoned me to his room for a chat.

How can you leave New York? he asked while filling out a check on top of a book on his lap. Back then he was still healthy, yet lanky, with a body that looked and moved like an aging dancers, a receding hairline and half a head of salt-and-pepper hair.

Removing his steel-rimmed bifocals so I could better see his amber eyes, he had added in his slow, scratchy voice, Your mothers here in Brooklyn. Im here. Two of your three brothers are here. You have no family in Miami. What if this man youre moving there for mistreats you? Who are you going to turn to?

The lecture ended with his handing me the equivalent of five months of his mortgage payments toward the wedding reception costs. Looking back now, I wish hed simply said, Dont go. Im going to get sick and I might die.

At the airport, my father was too weak to get out of the car to greet me.

The blistering heat made his breathing even more difficult, he explained on his cell phone, while waving from the drivers seat of his apple red Lincoln Town Car, a car he used as both a gypsy cab and a family car.

When he leaned over to open the door, he began to cough, a deep and hollow cough that produced a mouthful of thick phlegm, which he spat out in paper napkins piled up in a plastic bag next to him.

During the six months that hed been visibly sick, my father had grown ashamed of this cough, just as hed been embarrassed about his arms and legs over the many years hed battled chronic psoriasis and eczema. Then too hed felt like a biblical leper, the kind people feared might infect them with skin-ravaging microbes and other ills. So whenever he coughed, he covered his entire face with both his hands.

I waited for him to stop coughing, then leaned over and kissed him. The blunt edge of his high cheekbones struck my lips hard. He had taken to wearing a jacket even on the warmest days because he wanted to hide how much thinner hed become. That morning at the airport he wore a gray sweater, a striped blue shirt and navy pants that looked like they belonged to someone twice his size.

Im happy to see you, he said while tugging at his too wide shirt collar.

Merging into traffic at the airport exit, he asked about my husband and the house wed been renovating in the Little Haiti section of Miami for the past two years.

Any new developments? he winked. Baby?

Fedo, my husband, and I were waiting to complete the renovations before trying to get pregnant, I told him.

Youre thirty-five years old, he said. You have more childbearing years behind you than you do ahead.

Watching him effortlessly drive the same car hed been driving for nearly a decade, I felt my stomach cramp again. We had a few hours still before his doctors appointment, so he suggested we visit an herbalist that his pastor, a minister whose Pentecostal church my father had been attending for more than thirty years, had recently recommended.

Maybe the herbalist can examine us both, I suggested. At that point, I still wanted to believe that our discomforts might be comparable, something that a few herbs and aromatic plants could fix.

The herbalist saw us immediately even though we didnt have an appointment. A large Jamaican woman with a knit rainbow head wrap, she motioned my father to a chair next to a machine that looked like it was set up for an eye exam.

Before our iridology scans, she made us sign disclaimers saying we knew she wasnt a medical doctor and could not cure any illness. This, she explained, was a legal necessity even though she had healed many people-as my fathers pastor had told him-including some terminal cancer patients.

She snapped a picture of each of my fathers pupils, then enlarged them on a computer screen. Leaning in, she examined the whites of his eyes on the screen.

You need plenty of vitamins. She pointed out some tiny spots to prove it. You need to cleanse your system and unblock those lungs.

When she was done with him, she handed my father a printout listing some syrups and pills she offered for sale.

After my own eye scan, she told me I had an imbalance in my uterus.

Had I ever missed any periods? Had I taken a pregnancy test?

My father, whod been examining a catalog filled with pricey herbs, suddenly looked up.

I have no reason to take a pregnancy test, I told her. My husband and I, well, were not trying.

My father opened his mouth to say something, but his words dissolved into a long coughing spell, which led her to add a few more recommended items to his list.

Somethings going on with you, she told me, as we left with two hundred dollars worth of vitamins, coenzymes, liquid oxygen, and natural cough suppressants for my father. The eyes dont lie.

Dr. Padmans office was a sad and desperate place. Everyone in his waiting room, mostly Caribbean, African, and Eastern European immigrants, seemed to be struggling for breath. Some, like my father, were barely managing on their own, while others dragged mobile oxygen tanks behind them.

My brother Bob, who taught global studies at a nearby high school, was, because of his location and the free afternoons his work schedule allowed, my fathers most frequent waiting room companion. After a few visits, however, he too began dreading that gray and dingy room, its stale and stuffy smells, its peeling beige paint and anti-smoking posters, because it was the one place where our fathers predicament was most unambiguous, where his future seemed most uncertain. At the same time, it was where Papa appeared most comfortable, where he could cough without being embarrassed, because others were coughing too, some even more vociferously. In the skeletal faces and winded voices around him, he could place himself on some kind of continuum, one where he was still coming out ahead.

A nurse asked my father to step on a scale soon after we arrived. This was the part of the visits he would come to dread most, for it offered proof that he was indeed shrinking. Before he became ill he had carried 170 pounds on his five-eleven frame. During that July 2004 visit he weighed 128 pounds.

Next page