Morten Storm with

Paul Cruickshank

and Tim Lister

AGENT STORM

My Life inside al-Qaeda

Contents

Authors Note

Any spy who goes public will inevitably face scrutiny, especially one claiming to have worked as a double agent for four Western intelligence services on some of their most sensitive counter-terrorism operations after 9/11.

What makes Morten Storms story unique is the extraordinary amount of audiovisual evidence and electronic communications he collected during his time as a spy, which both corroborate his story and enrich his account.

This material, to which he gave us unfettered access, includes:

- emails exchanged with the influential cleric Anwar al-Awlaki;

- videos recorded by Awlaki and the Croatian woman who travels to Yemen to marry the cleric, a marriage arranged by Storm even as Awlaki was being hunted by the US;

- dozens of encrypted emails between Storm and terrorist operatives in Arabia and Africa that are still on the hard drives of his computers;

- records of money transfers to a terrorist in Somalia;

- text messages with Danish intelligence officers still stored on his mobile phones;

- secret recordings made by Storm of conversations with his Danish and US intelligence handlers, including a thirty-minute recording of a meeting with a CIA agent in Denmark in 2011 during which several of Storms missions targeting terrorists were discussed;

- handwritten mission notes;

- video and photographs of Storm driving through Yemens tribal areas just after meeting Awlaki in 2008;

- video of Storm with British and Danish intelligence agents in northern Sweden in 2010.

Unless otherwise stated in the endnotes all emails, letters, Facebook exchanges, text messages and recordings of conversations quoted in the book are reproduced verbatim, including spelling and grammatical mistakes. Some have been translated into English from Danish.

Storm also provided photographs taken with several of his Danish intelligence handlers in Iceland. Reporters at the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten were able to confirm the identity of the agents through their sources.

Several individuals mentioned in the book corroborated essential elements of Storms story. We have not disclosed the full identity of some of them for their own safety. No Western intelligence official was willing to go on the record.

Storm provided us with his passports, which include entry and exit visas for every trip outside Europe described in the book from the year 2000 onwards. He also shared hotel invoices paid by Mola Consult, a front company used by Danish intelligence, which according to Denmarks business registry was dissolved just before he went public. Additionally he provided dozens of Western Union receipts cataloguing payments by Danish intelligence (PET). His PET handlers listed Sborg the district in which PET is located in Copenhagen on the paperwork.

We used pseudonyms for three people in the book to protect their safety or identity, which we make clear at first reference. We have used only the first name of several others for security or legal reasons. A dramatis personae is attached at the end of the book. The book includes Arabic phrases and greetings; a translation is given at first reference.

We have added a number of photographs and other visual testimonies of Storms work in an archive at the end of the book and a colour picture section. These include a photograph of a briefcase containing a $250,000 reward from the CIA, handwritten notes from a meeting with Awlaki, decrypted emails, money transfer receipts, and video images and pictures taken in Yemens Shabwa province on trips to meet the cleric.

Paul Cruickshank and Tim Lister, April 2014

CHAPTER ONE

Desert Road

Mid-September 2009

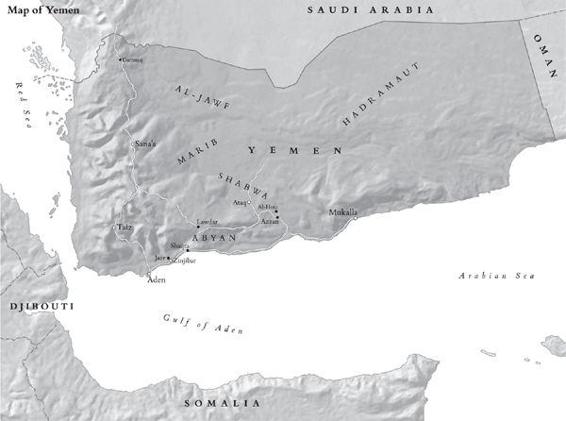

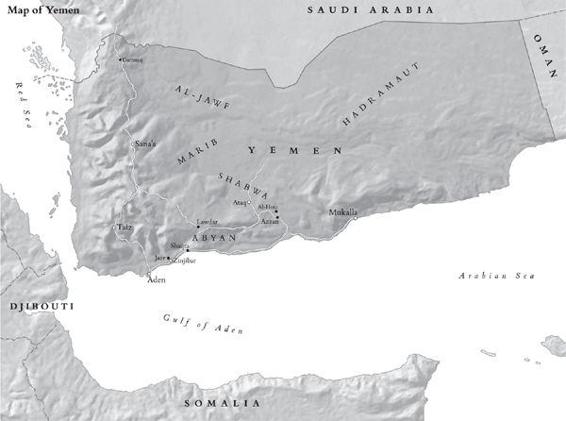

I sat in my grey Hyundai peering into the liquid darkness, exhausted and apprehensive. Exhausted because my day had started before dawn in Sanaa, Yemens capital, some 200 miles to the north-west. Apprehensive because I had no idea who was coming to meet me or when they would arrive. Would they greet me as a comrade or seize me as a traitor?

The desert night had an intensity I had never seen in Europe. There were no lights on the road that led from the coast into the mountains of Shabwa province, a lawless part of Yemen. At times there hadnt been much of a road either. A fine coating of sand had drifted on to the baking tarmac. Long after sunset, a humid breeze wafted in from the Arabian Sea.

My apprehension was fed by guilt: I had only been able to drive into this no-mans-land, where al-Qaedas presence was growing as the governments authority waned, because my young Yemeni wife, Fadia, was beside me. On the pretext of visiting her brother we had negotiated one checkpoint after another on a dangerous route south.

In my quest to reconnect with Anwar al-Awlaki, an American-Yemeni cleric who had become one of al-Qaedas most influential and charismatic figures, I knew I was risking my life. Yemens military and intelligence services had recently stepped up their attempts to combat al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), one of the most active and dangerous franchises of Osama bin Ladens group. There was the risk of an ambush, a shoot-out at a checkpoint or just a lethal misunderstanding.

There was also the danger that Awlaki now dubbed al-Qaedas rock star by Western newspapers might no longer trust me. My trip had been at his request. In an email he had saved in the draft folder of an anonymous email account we shared, he had told me:

It had been nearly a year since I had seen Awlaki and in that time he had continued a remorseless and fateful journey. The radical preacher sympathetic to al-Qaeda had become an influential figure within its leadership, aware of and involved in its plans to export terror.

I had already missed one rendezvous. Awlaki had invited me to come out to a meeting of Yemens leading jihadis in a remote part of Marib, a desert province that had reputedly been the home of the Queen of Sheba centuries earlier. Awlakis younger brother, Omar, was meant to organize my travel to Marib, but had insisted I dress as a woman in a full veil, or niqab, so that we could get through the checkpoints. At 6 foot 1 inch tall and weighing nearly eighteen stone, I was dubious. I had declined the offer, even though the driver who would take me to meet these wanted men was a police officer. Such were the contradictions of Yemen. My absence from such an important gathering of al-Qaedas leaders in Yemen had gnawed at me. So a few days later my wife and I undertook this odyssey to Shabwa.

After a few minutes I heard the muffled growl of a distant engine, then saw headlights and the approach of a Toyota Land Cruiser packed with serious young men brandishing AK-47s. The escort party had arrived. I grasped my wifes hand. If things were about to go very wrong, we would know in the next few moments.

All day we had followed curt directions texted from Awlaki, as if they were clues in some bizarre treasure hunt. Take this road, turn left, pretend to the police that you are going to Mukalla along the coast.

I could hardly blend in with the locals. As a heavy-set Dane with a shock of ginger hair and a long beard, I might as well have been an alien life form in a country of wiry, dark-skinned Arabs. In a land where kidnapping and tribal rivalries, trigger-happy police and militant jihadis made travelling an unpredictable venture, the sight of someone like me, with a petite Yemeni woman at my side, crammed into a hired car heading towards the rebellious south was to say the least an unusual one.

Next page