COLD

Also by Ranulph Fiennes

A Talent For Trouble

Ice Fall In Norway

The Headless Valley

Where Soldiers Fear To Tread

Hell On Ice

To The Ends Of The Earth

Bothie The Polar Dog (With Virginia Fiennes)

Living Dangerously

The Feather Men

Atlantis Of The Sands

Mind Over Matter

The Sett

Fit For Life

Beyond The Limits

The Secret Hunters

Captain Scott: The Biography

Mad, Bad And Dangerous To Know

Mad Dogs And Englishmen

Killer Elite

My Heroes

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2013

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright 2013 by Ranulph Fiennes

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Ranulph Fiennes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

The author and publishers have made all reasonable efforts to contact copyright-holders for permission, and apologise for any omissions or errors in the form of credits given.

Corrections may be made to future printings.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-47112-782-3

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-1-47112-783-0

eBook ISBN: 978-1-47112-785-4

Typeset in the UK by M Rules

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

For my daughter Elizabeth (Mouser)

With much Love.

Yours till Hell freezes

Sir Frederick Ponsonby

Recollections of Three Reigns (1951)

Foreword

M uch of my life has been governed by the cold. After leaving the army, I looked around for a civilian job to put bread on the family table. Cold places, cold survival skills and breaking cold world records would, I hoped, do the job.

I spent the early years of my childhood in sunny South Africa, followed by a family move back to England when I was eleven, and the first time I can remember feeling cold was at Eton College, when climbing the great dome of School Hall on a dark, wet and windy November night. This was an activity which, if discovered, risked expulsion. My climbing friend and I had left his old black tailcoat flying from the lightning conductor after a difficult ascent, but on returning to ground level not long before dawn, he owned up to a shocking oversight.

You will not believe this, Ran, but I think I forgot to remove my name tag. They will know it was me.

You mean... I gasped.

Yes. He shook his head in disbelief at his own stupidity, and, looking at his watch, hissed, We could just about get up there again, remove the tag and be back safe before the breakfast gong.

We? I was incredulous. You dont think Im going back up to get your coat and risk getting chucked out of school, do you? You must be joking.

But we both made it in time and retrieved his coat. I crept back through a rear window of my school house soon after dawn had broken, with hands numb and bleeding and shivering with cold. My teeth were still chattering in the breakfast queue an hour later.

After school and on leave from the army I dug my first snowhole and spent the night in it as part of a double wager with friends. The bet was that I would not ski up the main busy Aviemore ski run wearing only Y-fronts and ski boots, followed by a night with my girlfriend of that time in the shovelled-out snowscrape on the same piste run. That also proved a cold experience, though now just a hazy memory among a thousand and one other colder nights.

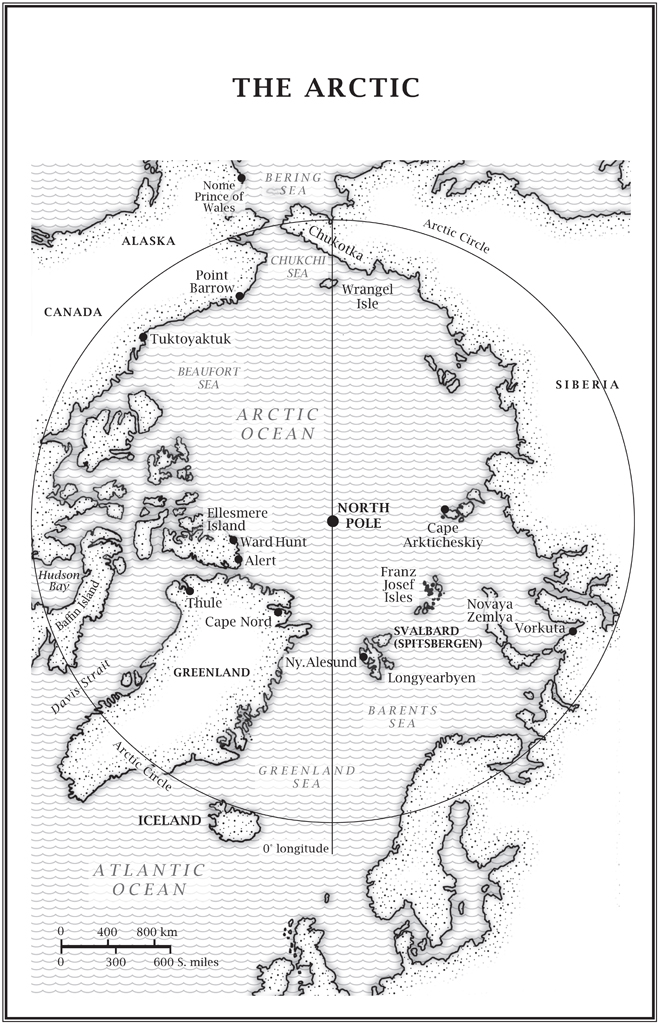

In the early 1960s I joined my late fathers regiment, the Royal Scots Greys. We were stationed on the German front line during the Cold War face-off, and I began to spend my annual leaves in Norway, usually with a friend and a canoe. By our fourth visit we had come to know the rivers and fjords of central Norway fairly well. The part of Norway which interested us most was the Jostedalsbreen, which contains the largest snowfield in Europe. Many valley glaciers, forever shifting, moaning and grinding in tortured response to the stresses of gravity, descend from this great reservoir of ice and snow. From the lakes at the base of these glaciers issue raging torrents which race down the valleys to the calmer levels of the fjords and so to the sea.

In 1965 a friend and I planned to canoe from the western mountains to Oslo, starting our voyage immediately below the Jostedalsbreen (or Jostedal Glacier). This river journey proved to be a wild dash through magnificent country, but we had completed less than a third of our intended route when our canoe was dashed to pieces in a cataract and lost.

Despite this failure, Norway still lured me back. Standing at the foot of the Jostedal Glacier before the canoe journey, I had peered up at the great ice cliffs soaring above and wondered what the plateau which caused such glacial outpourings might be like. I had been told that there were routes up to the plateau if you were fit and knew where to look, and that trails existed that led right over the ice fields from the side of the sea fjords to inland eastern Jotunheimen. Once herds of cattle and the famous fjord ponies of Jotunheimen were driven over these drift trails, for they had formed vital trade links between the coast and inland Norway. I learnt that the last drift of animals was taken across the ice in 1857, but then the gently sloping edges of the glaciers leading up to the plateau began to melt and recede, so that their slopes became too steep and dangerous for the animals.

In 1967, six of us decided to explore this area by following one of the old trails right across the plateau and then canoeing down one of the rivers running east from the Jostedal Glacier. The trip was a disaster, due both to bad equipment and to the poor skiing skills of two of the team. Nonetheless it was my first real taste of ice travel, and I was determined to try other ice travels.

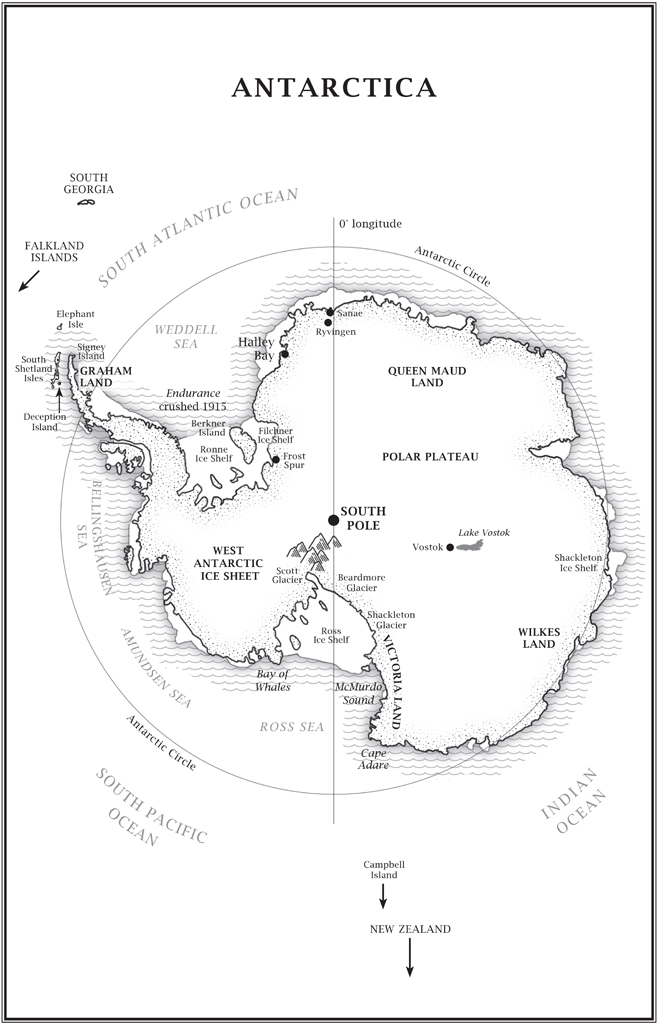

So I did, many times, and in 2013 I was part of a six-man team about to attempt what would be, quite literally, the coldest journey on Earth: a winter crossing of Antarctica. I had spent the previous five years organizing this endeavour. Then my left hand, already sporting five shortened fingers due to amputations a dozen years before, was further damaged by frostbite. The temperature at the time of the injury was 30C, with a steady breeze lifting the snow around my skis. I had travelled in far colder conditions over many years without any problem, so the frostbite came as a shock, inexplicable at the time.

The journey would now prove out of the question for me, for I knew well that fingers which could not put up with 30C would prove a major handicap on a six-month journey with temperatures likely to plummet well into the 80Cs. Forced to return prematurely from Antarctica, I decided instead to share my fascination with the wonderful world of all things cold, and this book is the result.