Tell the old faggot its gonna be the biggest thing that ever happened.

Bob Geldof persuading Queen to play Live Aid

Hello World!

Audience banner at Live Aid, Wembley Stadium

I have to win people over. Thats part of my duty. Its all to do with feeling in control.

Freddie Mercury, 1985

I t is 13 July 1985, and for rock stars of a certain vintage, its a difficult time. Many who came of age in the sixties and seventies are living off past glories and the blind goodwill of fans. The world has yet to invent the pensioner rock star, and Pete Townshends adolescent mission statement Hope I die before I get old has never seemed more ill-judged.

Todays Live Aid concerts in Philadelphia and London will unite musicians of every age. The common cause is to raise funds for Ethiopian famine relief, but there is another agenda. There are over eighty thousand people in the audience at Londons Wembley Stadium alone, and a satellite TV link-up means that a further 400 million people in over fifty countries will witness the action, both good and bad. Reputations will be made and lost, while those watching donate a total of 150 million to aid the starving people of Africa.

Over the next few hours, this global audience will see an under-rehearsed Bob Dylan, an underwhelming Led Zeppelin, and pop peacocks Mick Jagger and David Bowie shaking their tail feathers in each others faces. Live Aid will prove a pivotal moment in the careers of the still-novice U2 and Madonna, but will do nothing for the longevity of Adam Ant, Howard Jones or the Thompson Twins. For Dire Straits and Phil Collins, the ubiquitous multi-platinum-sellers of the day, it will never get any bigger than this.

Into this disparate mix comes a rock group with 14 long years on the clock. This multi-millionaire band (listed in the 1982 GuinnessBook of Records as Britains highest-paid company directors) have notched up a daunting run of hit singles and albums, with a restless musical style encompassing rock, pop, funk, heavy metal, even gospel. While their reputation as a supreme live act precedes them, even their most loyal supporters couldnt have predicted what would happen today.

At 6.44 p.m., the groups appearance is heralded by the arrival of TV comedians Mel Smith and Griff Rhys Jones. Smith is dressed as an officious police sergeant, Jones as his hapless constable. The gag is simple: authority versus the kids, and the pairs jokes there have been complaints about the noise from a woman in Belgium help whip up the crowd but are almost drowned out by the sound of the road crew behind them making last-minute adjustments. Finally, Smith removes his coppers helmet, jams it under his armpit, and stands to attention for Her Majesty Queen!

Interviewed later, Live Aids organiser Bob Geldof will try to describe the inherent oddness of these four individuals. Bounding onstage at Live Aid, they look, as Geldof says, like the most unlikely rock band you could imagine.

John Deacon (Geldof: the reserved bass guitarist) takes up his position at the back, close to the drum riser. Despite a pop stars shaggy perm, he most resembles the electronics engineer hed have become had a career in music not panned out. Earlier in the day, when the band had been summoned to line up and meet Live Aids royal guests, the Prince and Princess of Wales, thousands of Queen fans watching on TV wondered why a man that looked suspiciously like a roadie had taken John Deacons place. I was too shy to go and meet Princess Diana. I thought Id make a fool of myself, he said later, admitting hed sent his roadie, Spider, instead.

Brian May, of the praying-mantis physique and busby of dark curls (the hippy guitarist, says Geldof), looks almost unchanged since the group began. May undercut his guitar-hero posings with a naturally studious manner. For the Bachelor of Science and former schoolteacher, guitar playing is a serious business. In the early days, May would mutter under his breath like a tennis player psyching himself for an important point.

Meanwhile, you wonder if Roger Taylor isnt frustrated at spending his working life hidden behind a drum kit. With his blond coiffure and dainty features (he once grew a beard to stop people mistaking him for a girl) and offstage passion for sports cars and model girlfriends, Taylor is the bands most obvious pop star. In recent years, his bass drum skin has been decorated with a close-up picture of his face, visible from even the cheapest seats. While Taylor remains largely unseen, he will not go unheard; his distinct, cracked backing vocals are an essential part of Queens sound.

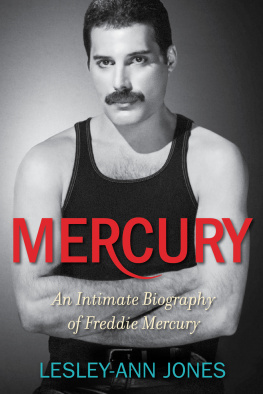

Whatever Freddie Mercurys bandmates do over the next twenty-two minutes, they rarely divert attention from, as Geldof calls him, that outrageous lead singer. At the very beginning, Mercury was a glam-rock pimpernel. Not now. The hair is short and greased back; the satin Zandra Rhodes creations of old replaced by a gym vest and snug pale jeans.

When it comes to his sexuality, Mercury has been playing cat-and-mouse with the press for years, but his image is clearly modelled on the Castro Clone look popular in US gay circles. The finishing touches include a studded bracelet circling his right bicep, and a dense moustache Freddies trademark almost, though not quite, covering his oversized teeth. When Mercury jogs on stage, his exaggerated gait suggests a ballet dancer running for a bus.

Its difficult to imagine any twenty-first-century music business Svengali or reality TV judge buying into the notion of the 38-year-old Mercury as a global pop star. And yet, in years to come, Mercury will have more in common with todays wannabes than history currently allows. Years before Live Aid, as an art student with musical ambitions, the man born Farrokh Bulsara told anyone who would listen that he would be a star one day. Few believed him.

Despite their usually unshakeable self-belief, the band are keenly aware that this not just their crowd. Not for them, then, the sloppy approach taken by some of their peers. This band have drilled themselves with four days of intensive rehearsals, timing their twenty-minute set to the very last second, and selecting their songs for maximum impact. After a quick lap of the stage, Freddie Mercury seats himself at a piano stage left. The audience erupts as he picks out the opening figure to Bohemian Rhapsody how else to start? crossing his hands with a camp flourish to play the high notes. As he delivers the opening line, the crowd responds again. The songs sense of melodrama is undiminished, despite the piano being adorned not with candelabra, but Pepsi-branded cups and plastic glasses of lager. Undaunted and already in the moment, Freddie manages to sing as if hes conveying a message of worldshattering importance. Today, Live Aid will belong to Queen.

The rest of the band joins in, with May weaving in his baroque guitar solo, and then, without warning, Mercury jumps to his feet, Bohemian Rhapsody cut off at its first big crescendo and before it overstays its welcome.

Freddies roadie Peter Hince hoves into view, passing the singer his instantly recognisable prop a sawn-off mic stand. Mercury prowls the lip of the stage, punching the air, cocking his head and pouting. Behind him, Taylor beats out the introduction to Radio Ga Ga, Queens number 2 hit from the year before. With its modish synthesiser and electronic rhythm it is the antithesis of Bohemian Rhapsody.

The songs lyrics are an indignant commentary on the state of modern radio, sweetened by a singsong chorus. But its promo video, with scenes lifted from the 1920s sci-fi movie