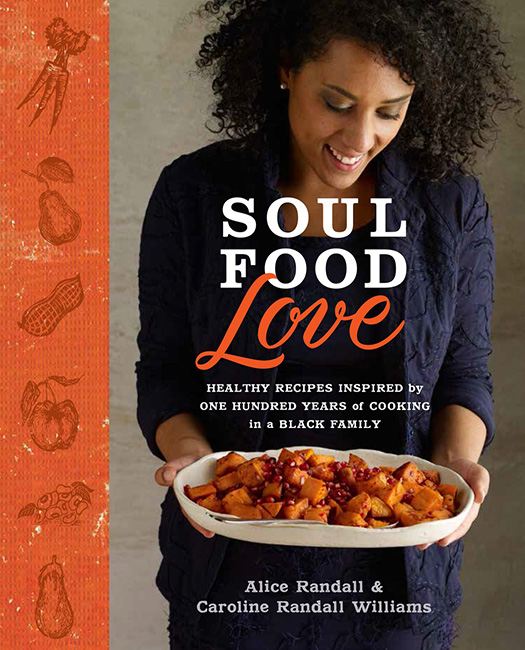

Copyright 2015 by Alice Randall and Caroline Randall Williams Principal photographs by Penny De Los Santos, copyright 2015 by Penny De Los Santos

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.clarksonpotter.com

CLARKSON POTTER is a trademark and POTTER with colophon is a registered trademark of Random House LLC.

George Washington Carver Vermont Olives first appeared in the Carver Bulletins (August 1936). Reprinted here courtesy of Tuskegee University Archives.

Archival photographs courtesy of the author. Photograph of is reprinted courtesy of the Nashville Public Library.

Pear and carrot illustrations courtesy of Hatch Show Print; other illustrations carved by Bethany Taylor specifically for this book and are used with permission of the artist. Hatch Show Print is owned by the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum and operated by the Country Music Foundation, Inc., a Section 501(c)(3) not-for-profit educational organization chartered by the state of Tennessee in 1964.

Preface

A TALE OF FIVE KITCHENS

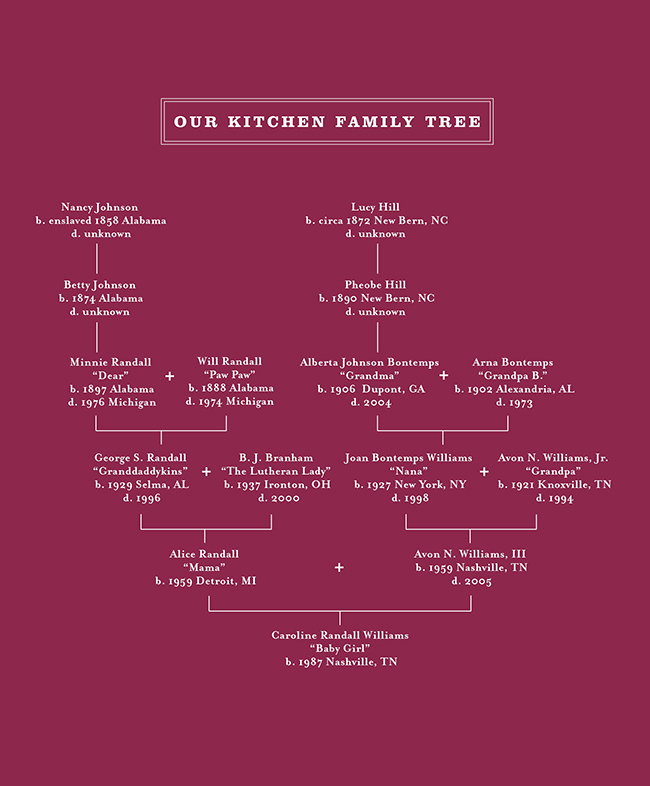

This cookbook tells the story of five kitchensthree generations of women who came to weighing more than two hundred pounds, and a fourth generation that absolutely refused ever to weigh two hundred pounds. Its the story of a hundred years of cooking and eating in one black American family.

On these pages we share the kitchen memories, kitchen gossip, and foodways that sustained two great-grandmothers, a grandmother, and us: a mother and a daughter.

Dears kitchen, Grandmas kitchen, Nanas kitchen, Mamas kitchen (Alices), and Baby Girls kitchen (Carolines). All are sacred places in our family. But only one is simple: Baby Girls.

The recipes in this book are from Baby Girls kitchen. You can cook every one from a Walmart shelf. Or you can cook them from your home garden, or Whole Foodsbut wherever you get your foodstuffs, cook these recipes and you will be tasting the past swerving into a new and healthier future. You will be tasting us using what we got to get where we want to goto Fitland without forgetting, shaming, or blaming traditional soul foods or traditional soul foodways.

Our kitchen celebrates forgotten soul food staples. We love sweet potatoes, peanuts, and sardines. Our ancestresses loved them, too. For us the path to our black food future runs through our black food past. And it requires radical change.

The kitchen has historically been a fraught place for many black Americans. Our family is among the many. It has been a place of servitude and scarcity, and sometimes violence, as well as a place of solace, shelter, creativity, commerce, and communion.

In our family, and in many Southern families, the abundant kitchen has become an antidote for what pains and afflicts us. Somewhere along the way, abundance became excess. Then the excess became illness.

Today the kitchen that once saved us is killing us. And avoidance of the kitchen is killing us, too. Foodways in much of black America are plain broke-down. Too many young black women have lower life expectancies than their mothers. And most dont even know it.

And its not just black America. The Sun Belt is now the Stroke Belt. Fat-fueled diseasesdiabetes, hypertension, stroke, and cancerravage the nation. But black America is particularly hard hit.

We can change that in the kitchen, on the quick and on the cheap. We know because we did it in our familyfought back hard against fat while holding proud to our table. Others are doing it, too, becoming kitchen-sink Amazonswinning the war on fatone tasty home-fixed and healthy meal at a time.

And by home-fixed were not talking just about where you cook. Were talking about what you cook. Were talking about connecting with our mothers mothers through taste. Were talking about celebrating all we created and all we endured by holding close to some of the flavors that were with us when we were creating and enduring.

And were talking about letting some of them go. Anything thats killing us is poison, not food.

The kitchens in this book are the kitchens that had the most impact on our bodies and lives. As with many black families, there are missing leaves in our family tree. Alices mother, who never cooked for Caroline and seldom cooked for Alice, was orphaned at five. The Lutheran Lady, as she styled herself, didnt know either of her grandmothers and barely remembered her mother. We think they were from Ohio. Those leaves remain lost.

But there are leaves aplenty. And they are scattered widely.

Kitchens, like people, migrate. The kitchens we will recollect were located, at various times, in three different Southern statesGeorgia, Alabama, and Tennessee; in the Midwestern metropolises of Detroit and Chicago; and in the imperial black city of the East Coast: Harlem.

Some of the kitchens that go into the making of our tables were constructed in dire poverty, others in sepia privilege. All of this allows us to claim: if youre a black American, our roots are likely to cross yours.

We cover a lot of territory.

Tracing kitchen migrations, weve encountered many surprises.

A pleasant one we found while shaking our culinary family tree: one of the earliest black vegan movementsthe black Seventh-day Adventists. Grandma spent a good part of her life as an Adventist cooking vegetarian recipes supplied by The Message, a black Seventh-day Adventist magazine.

All the surprises were not pleasant. Until we started working together on this volume, we knew the kitchen was a difficult territory for some black women, but we had never contemplated the significance of kitchen rapean event we discovered was sufficiently common in our family history as to merit the coining of a phrase so the atrocity might be better mourned.