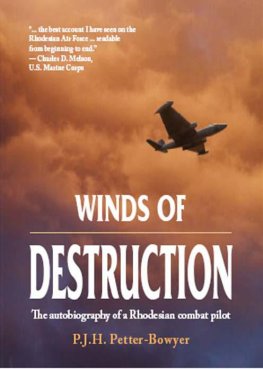

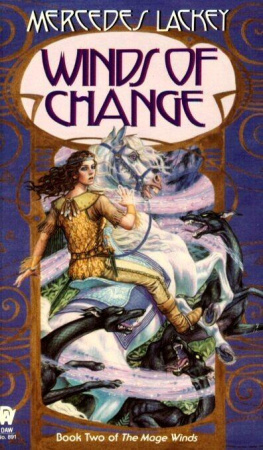

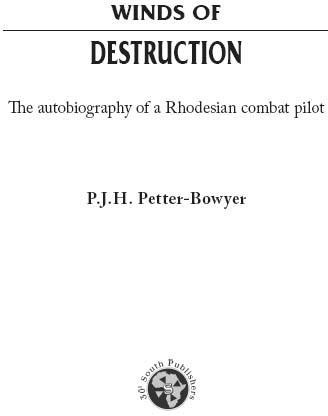

P.J.H. Petter-Bowyer

WINDS OF

DESTRUCTION

The Autobiography of a Rhodesian Combat Pilot

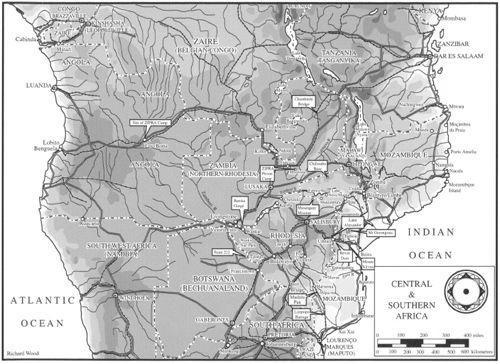

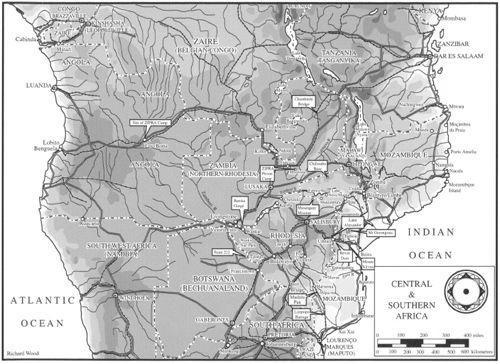

Central Africa and Southern Africa

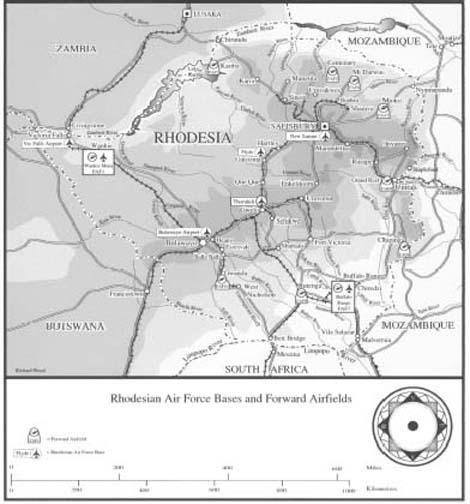

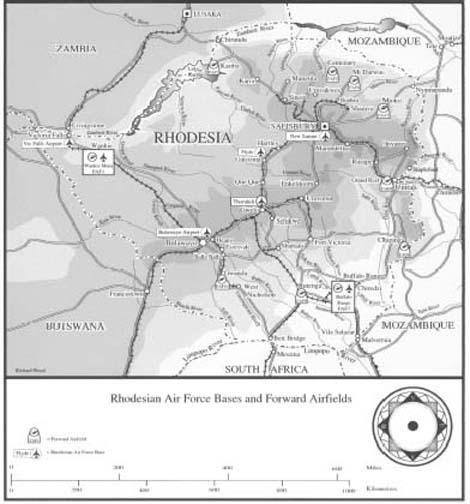

Air Force Bases and Forward Airfields

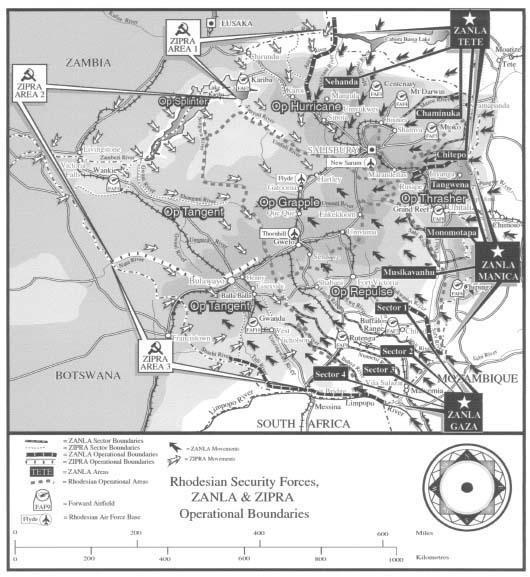

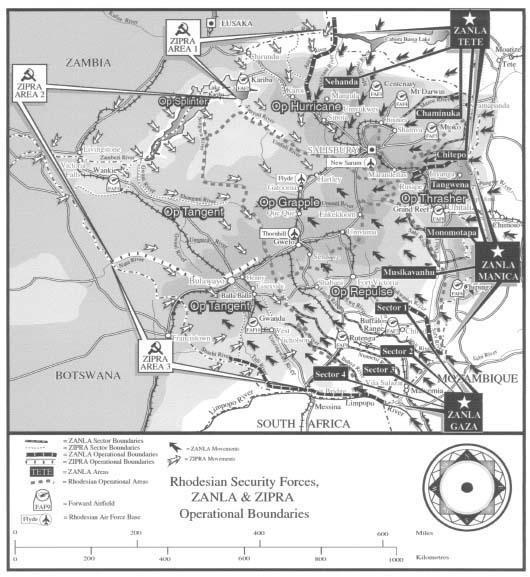

Rhodesian, ZIPRA and ZANLA Operational Boundaries

Foreword

I WILL NOT PRETEND THAT I have known Group Captain Peter John Hornby Petter-Bowyer, affectionately known as PB, as long as some have. After both having left our beloved Rhodesia, we lived in the same town, Durban, for years without encountering each other. Given my work on the history of Rhodesia, and my service in the Rhodesian Regiment and the Rhodesian Intelligence Corps, I knew his reputation, of course, indeed the awe in which this modest-to-a-fault airman was held within the ranks of the Rhodesian Security Forces. If our paths did not cross in daily life, I made it my business to interview him about what I knew of his achievements.

What PB presents us with in this book is a unique account of Rhodesia from the prosperous post-Second World War years to her death-throes in 1980. Unique because it is seen not just through the eyes of a pilot, because PB was seldom deskbound, rarely flying a Mahogany Bomber at headquarters, but through those of a Renaissance man, the proverbial man of great knowledge. PBs restless, inquiring mind never allowed him just to perform the task required of him. He was not what the Army thought of the typical pilot, homeward bound to clean clothes, a warm bed, fine food and the girls and the beer.

If PB was flying, he was thinking. Thinking about his aircraft. He was not an engineer but he would be responsible for many modifications of his aircraft, much to the irritation of a few of the technical staff. If he was bombing, he was thinking about the bomb, its purpose and whether it was achieving it. So it would be PB who would mastermind the invention and production of Rhodesias remarkable range of bombs. He did not do this alone, but his inquiring, inventive mind was the inspiration. The Rhodesian Air Force was condemned by circumstance to fly aircraft which elsewhere were obsolete, but the best had to be made of them, and not just by a high level of flying competence. The aging Canberra bomber (designed by PBs cousin, William Teddy Petter) was Rhodesias bomber equipped with a range of standard NATO bombs. PB soon saw ways to make it more effective even if metal fatigue would reduce the number of available Canberras. PB enhanced the humble air-to-ground rocket and gave the Hunter a formidable blast bomb, among other weapons. When a helicopter pilot, PB would enhance the Alouette IIIs refuelling ability, and assist in improving its weaponry.

It was not just a fascination with technology that marks the man. PB is not just an inventor; he was an inspiring and resourceful leader of the school that did not ask his pilots to do anything he would not do, and he would be the one doing it longer. Beginning with his helicopter days in the latter half of 1960s, PB was a leading counter-insurgency tactician. It was PB who realised that one could track from the air. Better than that, alone among the pilots, he realised that there were telltale signs, not just tracks, which betrayed the presence of his enemy. His self-imposed social anthropological research led him to become Rhodesias leading air-recce pilot when commanding No 4 Squadron. When PB appeared overhead in his stuttering Trojan, everyone in the ground forces knew something was about to happen, that the whereabouts of the quarry was about to be known. His training led to others acquiring this skill, and one at least bettered him, but it was PB who had the vision. He would carry that vision into every task that he performed.

I commend to you not just this inspiring pilots tale, but the man himself.

Professor J.R.T WoodDurban, South Africa

Authors Note

WHILE RESEARCHING MY FAMILIES backgrounds I ran into difficulties that forced me to rely entirely on faded memories of aged relatives because no written legacies exist. So in 1984 I started recording my own lifes story with the simple objective of leaving a permanent record, in hopes that my family would record their own historical narratives for successive generations to build upon. But then in January 2000 I was persuaded by Rhodesian friends to expand on what I had recorded, to meet a need for at least one Rhodesian Air Force story told at an individual level. Consequently this book is not an historical account of the most efficient air force of its day; nor does it cover important subjects that did not involve me either directly or indirectly. Nevertheless, my experiences are unique and sufficiently wide-ranging to give readers a fair understanding of the force I served, and reveal something of the essence of Rhodesia and her thirteen-year bush war.

In 1980, the long struggle to prevent an immensely successful country from falling into the hands of political despots, particularly Robert Gabriel Mugabe and his goons, was lost at political level. This was because of relentless international pressure against the white government of Ian Smith in favour of immediate black-majority rule. Britains ruling parties had not only failed to uphold promises of independence for Rhodesia, they totally disregarded every warning of the calamity that would befall the country and its people if one manone vote was prematurely forced into effect. Now, after more than twenty-five years in power, Robert Mugabes ZANU (PF) has exposed Britains disastrous folly and proven that Rhodesian fears were well founded. Too late to prevent the appalling mess that exists in modern-day Zimbabwe, our efforts to preserve responsible government have now been fully justified.

However, upon gaining power, Robert Mugabe and his ZANU (PF) cohorts became paranoid about the security of their personal positions. This led to the implementation of laws that ensured white Zimbabweans were denuded of personal weapons, military paraphernalia and any Rhodesian documentation that might be used against ZANU Having handed in my own weapons in 1980, I took the precaution of destroying all my diaries. This book reveals some of the reasons why such hasty action was taken but I have lived to regret dumping twenty diaries into the septic tank of our Salisbury home. In hindsight I realise that I should have buried them deep for later recovery. Nevertheless, the consequence of my error is that Winds of Destruction is, for the most part, written from memory. I offer no excuse for inevitable errors in detail that the ageing mind may have created, because the essence of this book is correct. Nor do I make any apology for naivet on political issues, as military personnel in my time were strictly apolitical and this may show in my personal opinions.

Central Africa and Southern Africa

Central Africa and Southern Africa Air Force Bases and Forward Airfields

Air Force Bases and Forward Airfields Rhodesian, ZIPRA and ZANLA Operational Boundaries

Rhodesian, ZIPRA and ZANLA Operational Boundaries