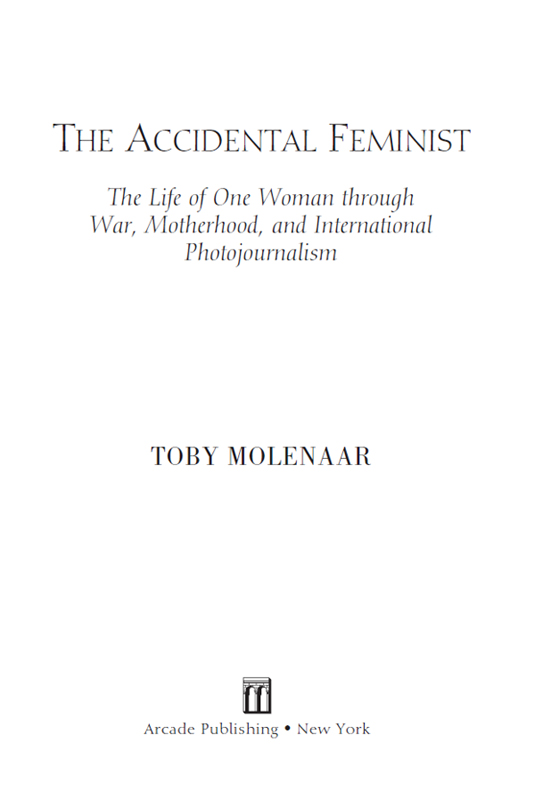

Copyright 2014 by Toby Molenaar

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62872-410-3

eISBN: 978-1-62872-411-0

Printed in the United States of America

To my children, Cathy, Marc, and Laura. And to Stanley, still my friend, without whom this book might not have published.

Les souvenirs sont cors de chasse Dont meurt le bruit parmi le vent.

Guillaume Apollinaire

I thank my editor Jeannette Seaver, as well as Lawrence Malkin and Ulf Skogsbergh for all their help.

Portrait painted by Mati Klarwein

Photographed by Ulf Skogsbergh

C ONTENTS

P REFACE

A s a child, walking to school, I used to chant names to myself, counting them like prayer beads: Samarkand, Zanzibar, Timbuktu, Kyoto and Surabaya. I had only a very vague idea where these places were or what they stood for, but I knew that one day I would go there. They were all still to come, the years of travel and discovery, of living and loving, the wonder and the sorrow of it. Seeing the golden stupa in Boudhanath, the white egrets in the flooded forests of the Amazon, or looking up at a star-filled Saharan sky, I would recognize the images of my childhood dreams.

More than forty years as a photographer have left me with a sizable archive. The pictures show me people of the deserts or of the misty rains, bringing back sights and sounds, smells and colors. The articles were written for publication and often screen my private emotions. The notes, scribbled in haste as an aide-mmoire to myself I should, I have, I must carry a sense of urgency tied to a specific moment. If together they form the texture of my life, they also remind me that memory is selective, biased and manipulative.

Memories, wrote Apollinaire, are the call of horns, their echo silenced by the wind. Even fantasy finds equilibrium between memory and lie. When I consciously search for images I become one with what emerges. I am there again, at that point in time, and find that all has remained unchanged. The child, the girl, the woman that was I is still within reach.

E CHOES

I n my dreams, I often have a husband. Not a new one, but a comfortable amalgam of the old ones. Perfectly nice, he seems to be au courant with my current life and I never have to say, Oh, of course, that was not with you! Sometimes he lingers a little after I wake up, but by the time I carry my coffee cup through the garden, down to the waters edge, I am alone to enjoy the clowning cormorant and the squabbling gulls. Actually, during the day I hardly think of any husbands and definitely not of the first one. He happened so long ago, long before Mallorca, Paris or Long Island and I seem to have left him behind somewhere. Except for unbidden snippets of memory recalled by such odd things as the sound of Swiss church bells on a Sunday morning, or a dead kitten in a trash can.

I was born in Holland, where although some of my ancestors built the massive windmills that dot the lowlands, most of them chose the sea. There was a fishing fleet that followed the herring; others built ships and repaired them. My grandfather built ships cabins of deep red mahogany, my father was one of the youngest officers in the merchant marine, my brother chose the navy before he decided to make his money elsewhere and a grandson recently graduated from the Marine Academy in New York, thus continuing the albeit thin line. I was told a great-grandmother used to sail with her husband across the Channel to deliver fresh vegetables to England. Sailors of the small fleet would grumble, as that was not done, but she was the captains wife and she did. I like to think of her standing beside her husband, skirts billowing, watching the daybreak over Englands coast, young, happy and alive.

I grew up in the noisy seaport of Rotterdam. Our house stood in a quiet tree-lined street with neatly trimmed hedges. Just behind our garden gate a narrow path lead to a dike beyond which stretched the empty polders , flat and windswept, the meadows furrowed by weed-covered ditches, where silver herons stood silent sentinel. A Dutch landscape scrawled in thin chalk. My brother and I gathered clumps of pearly frogs spawn in an old casserole and emptied them into the small pond in our garden; by early summer, they grew into a mighty chorus, invading the rest of the neighborhood. We jumped the sloten with long poles, fell in, disappeared under the jade-colored lichen into the mud and came up black and smelly. These ditches and the canal a block away from our house, where we skated in winter, were the nearest my everyday life then came to promises of oceans, deserts and jungles. But already my memory nudges at other images.

My grandfather used to visit an old sea captain of whom I was secretly very scared because he would take out his false teeth with horrible pink gums, thinking it amused me. He also had a blue and yellow parrot that sang Italian arias and swore in Spanish, or so I was told. It slept in a large round cage on a faded green velvet pillow but flapped around freely during the day, talking to itself in the mirror and screeching for sweets. Perched on the back of a chair it moved in small sideways steps, nibbling its clawed foot and quickly turning its head to give me a jaundiced look. It twice bit my finger. My sister said I would get rabies and die foaming at the mouth, but I always went back. Not for the bird, I realized later, but for what I thought it had seen.

I remember crossing silver bridges in the city, swift water rushing with the tide, forests of slender cranes swinging their loads into holds and white clouds that were always moving. I remember as a small girl spending a day on a tugboat of my fathers shipyard guiding a cruise ship into port, about twenty miles along the shifting sands of the river Meuse. All that afternoon boats hooted and bells clanged, men were calling to each other, there was the smell of brine, the sun was on the water, a long leash tied me to some metal railing and I had never felt so free. It was almost dark when we returned and the pilot climbed down from the cruise ship. Its lights reflected in the sky, I heard music, voices, and the hull above us loomed as high as a mountain. I looked up and wondered, Where has it been? What strange places did it see?

G ROWING U P

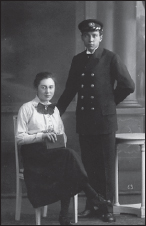

My parents

U ntil the warWorld War II, that ischanged it all, life was simple and rather predictable. We were a large family with six children, siblings who quarreled and made up, parents who despaired and were proud of us. We went to school, celebrated birthdays and waited with all the other Dutch children for Saint Nicolas (rather than Father Christmas) to bring us presents. We must have seemed a rather typical, somewhat noisy but closely knit family. I have a different memory.