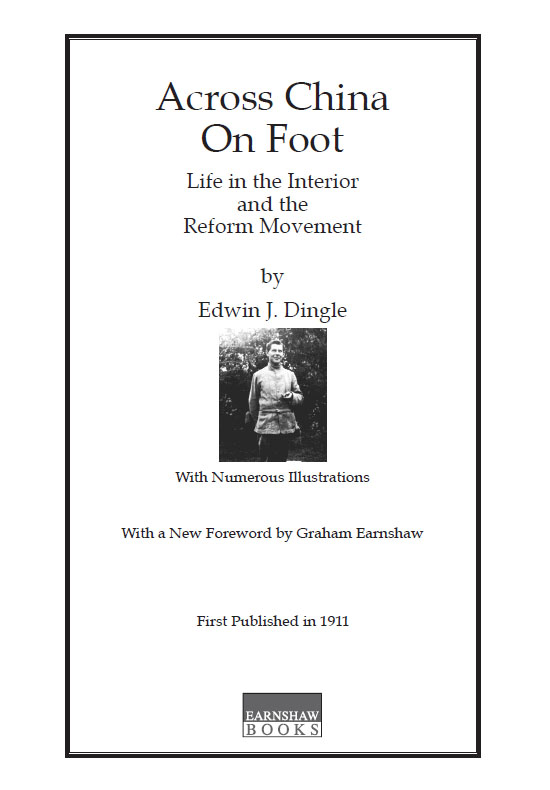

Across China On Foot

By Edwin J. Dingle

With a new foreword by Graham Earnshaw

PDF edition copyright 2011 Earnshaw Books

PDF ISBN-13: 978-988-8107-87-2

Print ISBN-13: 978-988-99874-4-2

Across China On Foot was first published in 1911.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in material form, by any means, whether graphic, electronic, mechanical or other, including photocopying or information storage, in whole or in part. May not be used to prepare other publications without written permission from the publisher.

Published by Earnshaw Books, Ltd, Hong Kong

Foreword

by Graham Earnshaw

Edwin Dingle was English, a journalist and publisher, and also an eccentric. And for various reasons, I feel a strong affinity with the man. Amongst other things, he changed my life, and gave me an idea which has led me down roads that I would never otherwise have seen. I owe him a lot.

This book, Across China on Foot, was published in 1911 and is the account of a journey through China. It is one of the most readable and entertaining books from that era, although the title is a little bit of a cheat - he didnt cross the whole of China on foot.

Dingle was born in 1881 and in the early 1900s was working in Singapore as a journalist. He and a friend, who remains tantalizingly unnamed through the portion of the story in which he is present, decided to embark on an adventure and they sailed off to Shanghai, and made their way up the Yangtze River on river steamers, houseboats and sampans to the city of Chongqing. By the time Chongqing was reached, the other man had given up the enterprise, and Dingle started out alone on foot, heading southwest. Well, not quite alone. He had his boy Lao Chang with him, and two coolies who carried everything including his typewriter, his camera and rolls of Eastman film.

So while he did not walk all the way across China, he did walk from Chongqing on the western edges of China as it then was all the way to the Burmese border, a distance of some 1,600 miles or 2,500 kilometers. He did it in around nine months, including periods when he was laid up sick, which is not bad going. And he did it at a time when the provinces he walked through - Sichuan and Yn-nan - were primitive and wild, far more primitive than the coastal cities of China where resident foreigners whined and complained about the servants and rickshaw pullers. Dingle, by contrast, actually walked through China. He did not use a palanquin - a chair carried by two coolies - and for whatever reason he also refused to ride a horse or a donkey.

He did not speak a word of Chinese, and his boy did all the communicating with those around him. Which leads me back to how he changed my life. I have lived in and around the China world since 1973, and in 2004, I was sitting in a Japanese restaurant in Shanghai reading this book and I thought: I can do better than this. So I started walking from Shanghai west across China, and at the time of writing, I have walked well over 1,000 kilometers and am currently in the middle of the Yangtze Gorges region, on the edge of old Sichuan. I am not able to do the walk contiguously as Dingle did it. I go out when I have the opportunity but always start from precisely the place I stopped the time before, so that I can truly say - unlike Edwin Dingle - that I really did go Across China On Foot.

I do speak Chinese, and that is a key part of the richness of the experience for me. Even in the early 21st century, I am a highly unusual sight as I walk through the Chinese countryside. For the vast majority of the people I come across, I am the first foreigner they have ever met, and I can gather a small crowd with little difficulty just by walking through a town.

But as a foreigner in those remote parts of China a hundred years ago, the reaction to Dingle must have been overwhelming. Here is a brief reference that gives a taste of Dingle and the experience:

At tiffin I counted thirty-three wretched people, who turned out to see the barbarian. They desired, and desired importunately, to touch me and the clothes which covered me. And I submitted.

The word tiffin reflects his Englishness, and the fact that the people are described as wretched is not racist, it is simply a statement of fact. They were desperately poor. They had no sense of shyness about touching the foreigner, and to his credit, Dingle let them do it. He had the superior attitude that any Anglo-Saxon had in those early years of the 20th century after Queen Victoria had died and before the Great War upset all the certainties of the age. But he was not arrogant, and while he has a wry sense of humor when observing the Chinese around him, he sees them as human beings not wholly unrelated to himself. Which is not bad for the time.

He was a journalist and while he was unable to talk to Chinese people except through his boy, he absorbed an enormous amount of life and society in southwest China. The non-Han minorities played a far bigger role in the region and were more numerous proportionately than they are today. Their lifestyles and cultures were stronger and more clearly defined, and Dingle describes what he sees in a readable and sensitive way, and makes full use of the views of resident foreigners, mostly missionaries, that he comes upon along his route.

He draws some macro geo-political conclusions from what he sees, basically concluding that the region had huge potential that simply required a rail line from Hanoi to the south to open it up to foreign trade and vast commercial opportunities. The rail line has existed for most of the past 100 years, but today that area of China remains poor, undeveloped and of small strategic and economic significance. Things could always change, of course. There are those even today who agree with Dingles overall view of the regions potential.

Dingle himself didnt stick around to see whether his predictions would come true. He was in Shanghai in the early 1920s, and was the proprietor and presumably founder of China and Far East Finance and Commerce, the predecessor publication of the Far Eastern Economic Review. But in the mid-1920s, he headed to the United States and wrote a number of books including one called Your Sex Life: Womanhood, Manhood, Marriage. An Inspirational Treatise On Sexology And Parenthood And Divorce. He founded his own health and sex cult in 1927 around the concept of Mental-physics, which kept him occupied until the ripe old age of 91 in a world far away from the one found in this book.

Graham Earnshaw

Shanghai

August 2007

IN GRATEFUL ESTEEM.

D URING M Y T RAVELS IN I NTERIOR C HINA I O NCE L AY AT THE P OINT OF D EATH. FOR T HEIR U NREMITTING K INDNESS DURING A L ONG I LLNESS, I N OW A FFECTIONATELY I NSCRIBE THIS V OLUME TO M Y F RIENDS, M R. AND M RS. A. E VANS OF T ONG-CHUAN-FU, Y UN-NAN, S OUTH-WEST C HINA, TO W HOSE D EVOTED N URSING AND U NTIRING C ARE I O WE M Y L IFE.

AUTHORS NOTE

To travel in China is easy. To walk across China, over roads acknowledgedly worse than are met with in any civilized country in the two hemispheres, and having accommodation unequalled for crudeness and insanitation, is not easy. In deciding to travel in China, I determined to cross overland from the head of the Yangtze Gorges to British Burma on foot; and, although the strain nearly cost me my life, no conveyance was used in any part of my journey other than at two points described in the course of the narrative. For several days during my travels I lay at the point of death. The arduousness of constant mountaineering for such is ordinary travel in most parts of Western China laid the foundation of a long illness, rendering it impossible for me to continue my walking, and as a consequence I resided in the interior of China during a period of convalescence of several months duration, at the end of which I continued my cross-country tramp. Subsequently I returned into Yn-nan from Burma, lived again in Tong-chuan-fu and Chao-tong-fu, and traveled in the wilds of the surrounding country. Whilst traveling I lived on Chinese food, and in the Miao country, where rice could not be got, subsisted for many days on maize only.

Next page