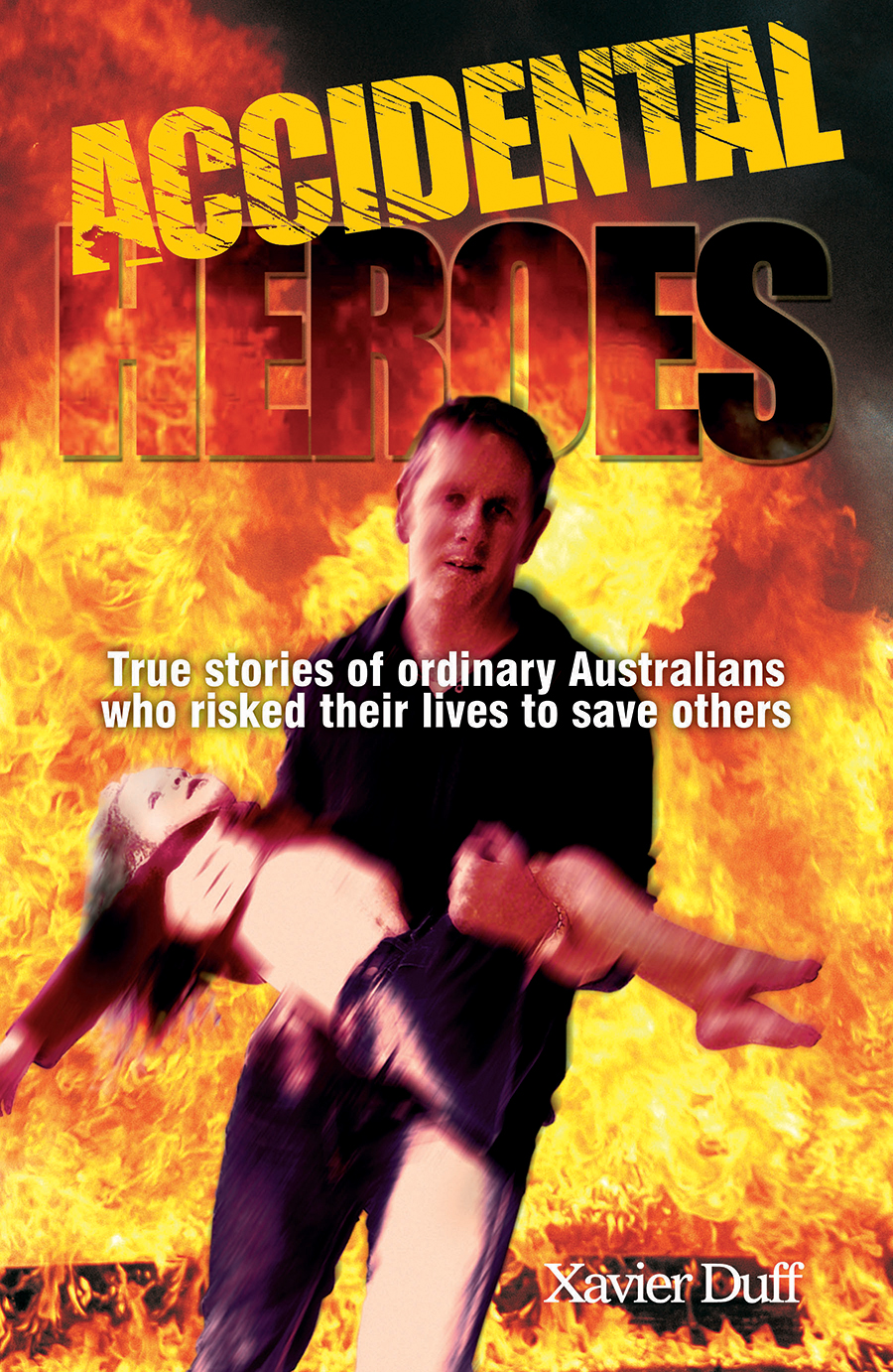

Accidental Heroes

True stories of ordinary Australians who risked their lives to save others

Xavier Duff

To Clancy and Anne Duff

and all the quiet achievers

Preface

Hero. It is an accolade thrown about with relative abandon these days, in a world obsessed as it is with celebrity and fame. The title once reserved for those carrying out acts that were truly courageous, selfless and life-threatening is now used to describe just about anyone and any achievement. Everyone from sports stars to business people has had the title bestowed upon them, led by the media in their bid to satisfy our seemingly insatiable appetite for stardom. In the words of the Olympic motto, you just have to run faster and jump higher to be a hero, or simply show determination in the face of defeat. It has become just another synonym for winner.

The sporting arenas, even the bland offices of corporations, are todays venues for the heroic deed. In a world where gladiators no longer take to the arena to fight to the death, where the battlefield has largely been replaced by technological war, many heroes today are made on the track and oval, the pitch and the court. These are our modern-day gladiators, our version of the Greek and Roman mythical heroes whose deeds inspired humanitys glory. But are they heroes? They are figures to be admired, certainly, revered even for their skill, endurance and ability. But heroes, in the truest sense, they are not.

The true hero is someone prepared to risk the thing most precious to us all: life. Heroes are those prepared for the ultimate sacrifice. No one risks their life for another on the sporting field. Certainly no one actually lays down their life for their team. We may use the language of heroism in sports but determination should not be mistaken for courage; pride is not valour. Ultimately these heroic deeds are just metaphors, for sports people only play at heroes. It is our willingness, then, to bestow the title so readily that illustrates how much we crave heroic figures. Like any culture that has preceded us we need real heroes to inspire us and help us make sense of ourselves. For what are we if we are not ultimately to rise beyond our fears, to excel, to be worthy?

The truly brave hero represents all that is good about humans. They inspire us to greatness and to better things, they counterbalance our opposing natural progressions to fear, selfishness and self-preservation. They make us think about how we, personally, would respond to the ultimate challenge. And that is a question we have probably all asked ourselves at some time in our lives when we pick up a newspaper or watch a TV program and hear about someone carrying out an amazing act of bravery. It may be a worker entering a toxic space to drag a fallen mate to safety, a woman risking her life to save a child swept away by a rip, or a person tackling a knife-wielding maniac who is threatening to kill an innocent bystander.

When the devastating tsunami hit Asia on Boxing Day 2004, there were tales of incredible courage as people struggled to save others caught in the crushing torrents of water and debris. A Canadian dive shop operator in Thailand paddled out in a sea kayak into the waves to save a Thai fisherman swept off his boat and was then tossed into the sea by the wave. When the tsunami devastated the island of Katchall, an Indian policeman, instead of running for his life, stayed on the beach to warn people of the looming disaster, gathering up children and the elderly and taking them to safety before finally drowning when the wave hit. A Sri Lankan minister rounded up the 26 children in his orphanage and put them in a boat to face the wave head on and in doing so saved all their lives.

On 11 September 2001 we heard countless stories of selfless acts, from the New York firemen on their ultimately fruitless mission to save lives to those who overpowered the terrorists on Flight 93 over Pennsylvania, bringing their deadly mission, and all the lives on board, to an end. And as we shake our heads in admiration and even disbelief, we ask: how would I react to a situation like that? How would I respond to the ultimate call to risk my life to save that of another? And while we would like to know the answer, we would also not like to be in the position which might give us the truth, for it would mean being exposed and vulnerable. We could die.

We all like to think we would respond in heroic fashion. But we might also dither and be frightened, and commit our biggest fear of all: simply run away and do absolutely nothing. We might find ourselves wanting, falling short of our expectations of ourselves. Fortunately most of us will never know. Thankfully we will probably never be in the position to discover the answer, because only a few end up being put to the test.

In some ways we have lost the potential for creating modern heroes. Twenty-first century warfare has become more clinical and technical, with its written rules of engagement and smart bombs that remove much of the bloody deadly slog that characterised past wars. The world generally is now largely explored and conquered, measured and contained, analysed and risk-managed. The opportunities for danger terrorism notwithstanding uncertainty and adventure, which are the breeding grounds for heroism, are increasingly rare.

But then all risk cannot be eliminated. Humans still make mistakes and new forms of danger, such as violent crime, still create the opportunities for bravery. For each who discovers their heroic side, they learn something about themselves that most of us will never know.

And in Australia there have been more than 7000 civilian heroes since 1874: the accidental heroes who have been called to the test and found themselves worthy. These are the people many of them ordinary Australians with no special training or skills who have received bravery awards, a system of honours designed to reward and encourage heroic deeds.

But assuming no one would risk their lives for another in the expectation of being rewarded with a medal, what is it that possesses some people to carry out a truly heroic deed, to knowingly put their lives in real danger, to take that step over the precipice in order to save another? What indeed is bravery itself? Is it our biology or our psychology at work? Is it pure instinct or something shaped by our experiences, our education, our family, our morals? This book is an attempt to answer these questions. But it is foremost a tribute to 18 individuals who did face the ultimate test of humanity. And all of them did not find themselves wanting.

Chapter 1

Terror in the Tropics

Natalie Goold and Tim Britten

There are moments in time when the human mind can fail utterly to comprehend the reality confronting it: moments when the world as you know it suddenly fails to make sense, and you just cant take in whats happening. Grief induces such moments. So does catastrophe: events that, like a lightning bolt, jam the brains receptors, stripping the world around you of all meaning so that you cant be sure whether you are experiencing reality or dream.

Such a moment would have descended on the revellers at Balis Kuta Beach one Saturday evening in October 2002. Except this lightning bolt was far more powerful than nature could summon. As the tourists danced and attempted to make themselves heard above the hubbub of music and party-talk, it is hard to know what, if anything, they sensed first the blinding flash, the ear-bursting boom or the ground trembling beneath their feet, as if a quake, deep from the bowels of the earth, had rippled to the surface releasing its giant waves of energy. But this was no natural tremor. The shock wave passing through this tourist Mecca was entirely man-made, the creation of evil minds intent on inflicting maximum mayhem, in their self-declared war on western civilization.