This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHING www.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1945 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2013, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

Wings at War Series, No. 1

THE AAF IN THE INVASION OF SOUTHERN FRANCE

An Interim Report

Published by Headquarters, Army Air Forces Washington, D. C.

Office of Assistant Chief of Air Staff, Intelligence From Reports Prepared by MAAF

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

FOREWORD

Originally published shortly after key air campaigns, the Wings at War series captures the spirit and tone of America's World War II experience. Eyewitness accounts of Army Air Forces' aviators and details from the official histories enliven the story behind each of six important AAF operations. In cooperation with the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Center for Air Force History has reprinted the entire series to honor the airmen who fought so valiantly fifty years ago.

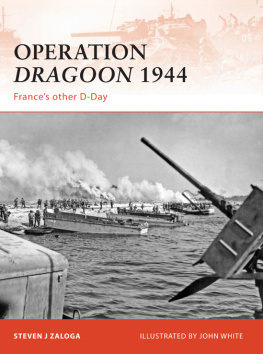

The AAF in the Invasion of Southern France tells how the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces, under the command of Lt. Gen. Ira Eaker, supported the Allied airborne and amphibious assault designed to undercut German defenses in Occupied France. In this invasionthe fourth major one in three monthsAmerican air power overwhelmed the meager enemy forces and diverted attention from the north, helping to topple German control in Vichy. Air operations persistently found, fixed, and fought occupying German forces, preventing their orderly withdrawal, greatly easing the way for Allied invasion forces.

The Invasion of Southern France

PRE-INVASION SITUATION

WHEN Allied airborne and amphibious troops invaded southern France in the early morning of 15 August 1944, they set in motion the fourth major onslaught against the occupied Continent in 3 months. First blow had been struck in Italy with the Allied offensive which began on the night of 11-12 May and had carried forward some 200 miles to the Pisa-Rimini line, liberating Rome and liquidating at least a dozen German divisions. Second blow had been the cross-channel invasion of Normandy which began on 6 June and had broken the German 7th Army, surrounded most of it, and was on the verge of capturing Paris. Third blow had been the massive Soviet attack across the Pripet Marshes which began on 22 June and had split the Baltic States at Riga, reached Warsaw in Poland, and was poised on the boundaries of East Prussia itself.

This was the picture on 15 August, the date set for invasion.

Thus the new Allied uppercut against southern France found the Germans in a situation which was already desperate. Though the Allied threat to the Riviera had been obvious for months, the hard-pressed Germans had been obliged to pull away a sizable proportion of the forces they had allocated to defend it. Only 10 Nazi divisions remained south of the River Loire and but 7 were actually deployed along the Mediterranean coast. Even more depleted, after a year of strategic bombing by the Allies, was the German Air Force. It was estimated to have in southern France the puny total of 200 operational aircraft, of which 130 were bombers designed for antishipping attacks. It was believed that the Hun might be able to scrape together from Italy and northern France another 50 bombers and 80 single-engine fighters. As for German naval defenses, these consisted of a handful of destroyers and torpedo boats and perhaps 5 U-boats.

Depleted and dispersed though the German defenses were, their capabilities were still considerable. The coast they were guarding is a rugged one, with rocky promontories overlooking the small beaches. The French had long ago established a number of well-sited coastal batteries at the obvious points. These the Germans increased, while they also deployed some 450 heavy and 1,200 light antiaircraft guns in the area, largely along the shore. Finally, there seemed little chance of tactical surprise since the Allied build-up in Corsica was clearly visible to German reconnaissance aircraft.

For the invasion the Allies marshalled a force with a clear-cut and overwhelming superiority in every respect. Against the Luftwaffe's 200 furtive aircraft, the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces could muster 5,000. Against the 7 weak German divisions the United States Seventh Army could throw in a stronger force of crack United States and French divisions, plus an assortment of paratroop, Commando, and Special Service forces. And the dinky German naval units would sally, if they dared, in the face of 450 British, United States, French, and Italian warships, including about 5 battleships and 10 aircraft carriers.

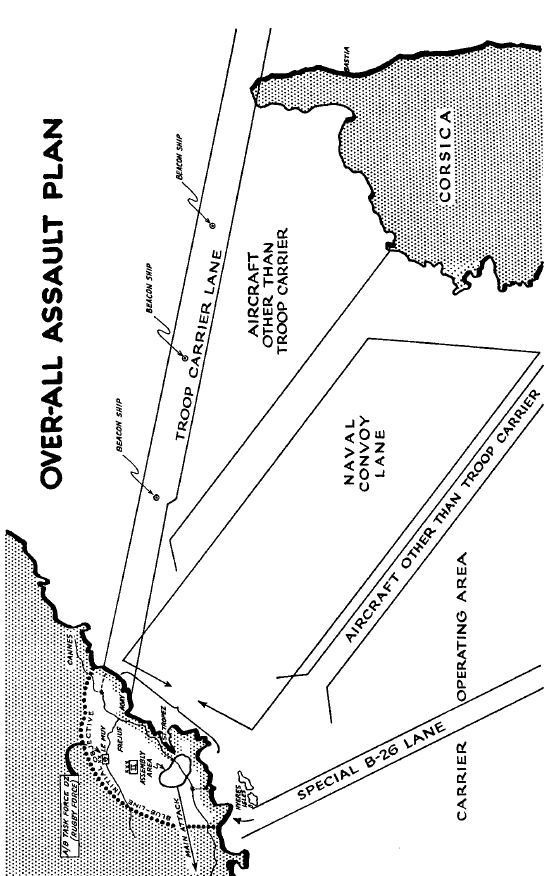

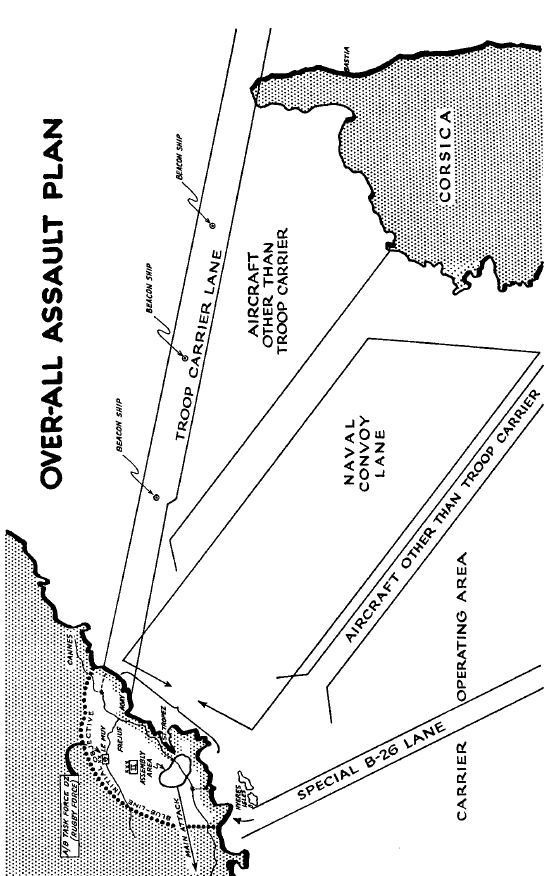

In collecting this mighty array, the Allies had faced two difficult problems: (1) the redeployment of the available ground and air forces so as to be able to hit southern France without at the same time hamstringing the advance of the Fifth and Eighth Armies in Italy, and (2) the build-up of primitive, malarial Corsica into a satisfactory springboard for the air participation in the landings. Both these matters are dealt with later. It suffices for this introductory summary of the situation to record that XII Tactical Air Command under Brig. Gen. Gordon P. Saville was charged with the responsibility of providing the air cooperation. By D-day it was effectively installed on 14 Corsican operational airfields, with all supplies needed to maintain about 40 United States, British, and French squadrons, plus some 6 squadrons on loan from the Strategic Air Force. Other elements of MAAF on call from XII TAC were based as follows: Provisional Troop Carrier Air Divisionwest coast of Italy above Rome; Desert Air ForceNorth Central Italy; Tactical Air Force's medium bombersCorsica and Sardinia; Strategic Air ForceFoggia area; Coastal Air Forcescattered throughout area; and, finally, a Carrier Task Force, standing offshore between Corsica and Toulon.

INTENTION

The major purposes behind the operation were (1) to assist the Normandy attack by engaging German forces that might otherwise be used in northern France; (2) to capture a major port through which large-scale reinforcements could flow; (3) to liberate France; and (4) to join up with the cross-channel invasion for the decisive battle with the German armies of the west.

The initial assignment of the Seventh Army, as stated in its Field Order No. 1, was to "assault the south coast of France, secure a beachhead east of Toulon and then assault and capture Toulon." Thereafter its intention was to advance toward Lyon and Vichy or westward to the Atlantic as determined by developments, eventually joining up with the Allied armies in northern France.

Next page