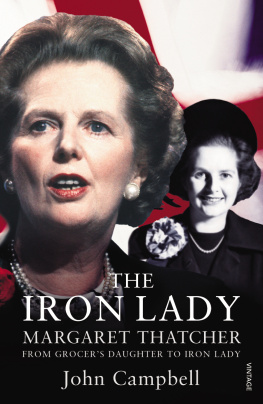

John Campbell

THE IRON LADY

Margaret Thatcher, From Grocers Daughter to Prime Minister

Abridgement by David Freeman

For Robin and Paddy two of Thatchers children

THIS book was originally published in two volumes totalling more than 1,200 pages.The present volume is drastically reduced to make it more accessible to the general reader. Inevitably much of the detail and some of the colour of the original have been sacrificed. But I hope that the integrity of the book has been preserved. I am immensely grateful to David Freeman of the University of California for carrying out the work of abridgement so skilfully. I could not have done it myself, but I think he has done a superb job. If there is now a somewhat greater emphasis on foreign relations and the major enduring themes of Lady Thatchers life and rather less on her early life and the small change of party politics, I think that is appropriate as her career moves into a longer historical perspective. It is now 30 years since she came to power and 19 since she fell. In that time the world has continued to evolve: some of the hopes raised by the ending of the Cold War have not been realised, while Islamist terrorism, climate change and now a global financial crisis pose new problems scarcely imagined in her day. Beyond a very brief contemporary conclusion to the last chapter, however, I have not attempted to rewrite the original book. Remarkably little new information has emerged which requires substantial reinterpretation or revision. Most of the assumptions and judgments I made in 2000 and 2003, I believe, still stand. They are themselves part of the record of the time. For two decades after her fall Margaret Thatcher continued to exercise a powerful grip on the imagination of the country and of her successors. But already a new generation is growing up who scarcely remember her. I hope that this book, in its shortened form, may serve as a useful introduction to them, as well as a reminder to those who lived through the high drama of what will always be the Thatcher years. Those whose appetite is whetted may wish to go back to the original volumes for more detail.

I incurred an immense number of debts during the nine years it took me to write this book: scores of interviews, dozens of more casual conversations, many valuable pointers from friends and colleagues, much help from librarians and archivists. But I made due acknowledgement for all this help in the original volumes, and I hope it will be understood if I do not repeat my thanks in detail here: most of the interviewees are credited in the notes. I do, however, need to thank again HarperCollins, for allowing me to use substantial quotation from Lady Thatchers memoirs and also from Carol Thatchers biography of her father; Macmillan for allowing me to quote from Woodrow Wyatts diaries; David Higham Associates for permission to quote from Barbara Castles diaries; and Brook Associates for allowing me to quote from interviews for their television series The Seventies and The Thatcher Factor. I confess that I have not sought specific permission for every quotation I have made from the many other memoirs and diaries of the period but I am grateful to all those authors who put their memories into the public realm. I am also grateful to the United States Government for allowing access to and quotation from the papers of Presidents Carter, Reagan and Bush under the Freedom of Information Act, and to the staff of the three presidential libraries who guided me to what I needed to see on a necessarily short visit to the States in 2001. Finally I should like to thank again my publishers Dan Franklin at Jonathan Cape for the original volumes and now Alison Hennessey at Vintage for handling the abridgement; my agent Bruce Hunter; my children Robin and Paddy; and finally, for her love, faith and companionship over the past five years, Kirsty Hogarth. To all of them my debt is incalculable.

John CampbellDecember 2008

A FORMER town clerk once described Grantham as a narrow town, built on a narrow street and inhabited by narrow people.1 It is a plain, no-frills sort of place, brick-built and low-lying: at first sight a typical East Midlands town, once dubbed by the Sun the most boring town in Britain.2 Yet Grantham was once more than this. Look closer and it is a palimpsest of English history. Incorporated in 1463, it was a medieval market town. Kings stopped there on their journeys north: Richard III signed Buckinghams death warrant in the Angel Hotel. St Wulframs church boasts one of the tallest spires in England. Englands greatest scientist, Isaac Newton, was born seven miles south of the town in 1642 and educated at the grammar school.

Beatrice Stephenson Margaret Thatchers mother was Grantham born and bred. She was born on 24 August 1888. Her father, Daniel Stephenson, is euphemistically described as a railwayman: he was actually for thirty-five years a cloakroom attendant.3 He married, in 1876, Phoebe Crust, described as a farmers daughter (which might mean anything) from the village of Fishtoft Fen, near Boston, who had found work in Grantham as a factory machinist. Beatrice, one of several children, lived at home in South Parade until she was twenty-eight, working as a seamstress. Her daughter says she had her own business; but whether she worked alone or employed other girls there is no record. In December 1916 Daniel died. Five months later, on 28 May 1917, Beatrice married an ambitious young shop assistant four years younger than herself whom she had met at chapel: Alfred Roberts.

He was not a Grantham man, but was born at Ringstead, near Oundle in Northamptonshire, on 18 April 1892, the eldest of seven children of Benjamin Roberts and Ellen Smith. The Roberts side of his family came originally from Wales but had been settled in Northamptonshire as boot and shoe manufacturers for four generations. Alfred broke away from shoemaking. A bookish boy, he would have liked to train to be a teacher, but was forced to leave school at twelve to supplement the family income He spent the rest of his life reading determinedly to make up for the education he had missed. He went into the grocery trade and after a number of odd jobs over the next ten years came to Grantham in 1913 to take up a position as an assistant manager with Cliffords on London Road. It was while working for Alderman Clifford that he met Beatrice Stephenson. They are said to have met in chapel; but she may well have been a customer as well. However they met, Alfred soon began a lengthy courtship.

As a young man born in 1892 Alf was lucky to survive the Great War. He was tall, upright and good looking, but seriously short sighted. All his life he wore thick pebble glasses. He tried to enlist, but was rejected on the grounds of defective eyesight. Spared the fate of so many of his contemporaries, he was free to pursue his chosen trade. He worked hard and saved hard, and by 1917 he and Beatrice he called her Beatie had saved enough to marry. At first Alf moved in with Beatie and her mother, but within two years they were able, with a mortgage, to buy their own small shop at the other end of town in North Parade. Phoebe came to live with them over the shop. Their first child, christened Muriel, was born in May 1921. Their second, another daughter, did not come for another four years, by which time Beatrice was thirty-seven. Margaret Hilda Roberts the choice of names has never been explained was born over the shop on 13 October 1925.

The shop was a general store and also a post office. This is something which the iconography of Thatcherism tends to overlook; yet it subtly changes the picture of Alfred as the archetypal small businessman and champion of private enterprise. He was that; but as a sub-postmaster he was also an agent of central government, a sort of minor civil servant. The post office franchise was an important part of his business. The Post Office Savings Bank was the only bank most people knew; and old-age pensions had been paid through the post office since their introduction in 1908. The elderly of north Grantham collected their weekly ten shillings from North Parade. To this extent Alfred even in the 1920s and much more so after 1945 was an agent of the nascent welfare state; and Margaret was brought up with first-hand knowledge of its delivery system.