Copyright 2011 by Glenn Stout

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Sandpiper, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stout, Glenn, 1958

Yes she can!: womens sports pioneers/by Glenn Stout.

p. cm.(Good sports ; 2)

ISBN 978-0-547-41725-7

1. Women athletesBiography. 2. Sports for womenHistory. I. Title.

GV697.A1S74 2011

796.0922 dc22

2010022984

eISBN 978-0-547-57409-7

v2.0214

This book is dedicated to

S AORLA S TOUT,

P IPER D EAN,

A INSLEY D EAN,

and all my other young friends

and readers who are Good Sports

Introduction

Girls dont do that.

Girls shouldnt do that.

Girls cant do that.

Have you ever heard someone say that? Well, not very long ago, thats exactly what many people said whenever a woman tried to play a sport or do anything athletic. Most people believed that women were physically too weak and delicate to play sports. There might as well have been a sign at the gymnasium door that said MEN ONLY.

Fortunately, some women didnt believe what they were told. When these sports pioneers were told Girls dont, they did. When they were told Girls shouldnt, they asked Why not? And when they were told Girls cant, they became more determined than ever. This book tells the stories of several pioneers in womens sports, all of whom refused to be told what they could and could not do. And because they proved that girls can do anything, women today compete in sports of all kinds, from track and field, figure skating, and swimming to tackle football and racecar driving. Sports not only provide good exercise, they also help participants gain self-confidence and learn to work together and set goals.

It took some remarkable women to show everyone else the way. Thats what Gertrude Trudy Ederle, Louise Stokes, Tidye Pickett, Julie Krone, and Danica Patrick all have in common. When these girls were told they could not do something, they made even those who had doubted them say, Yes, she can!

TRUDY EDERLE

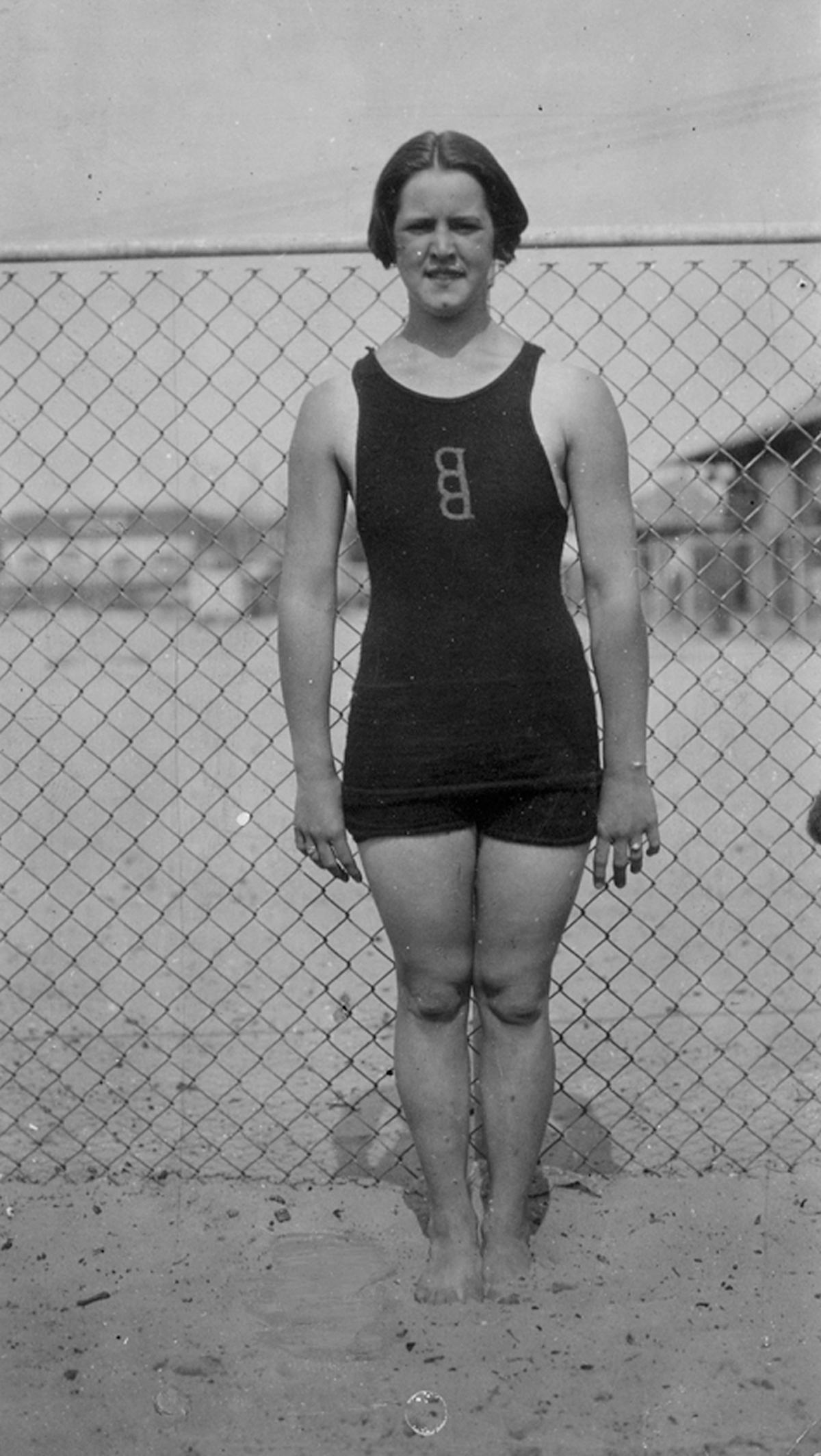

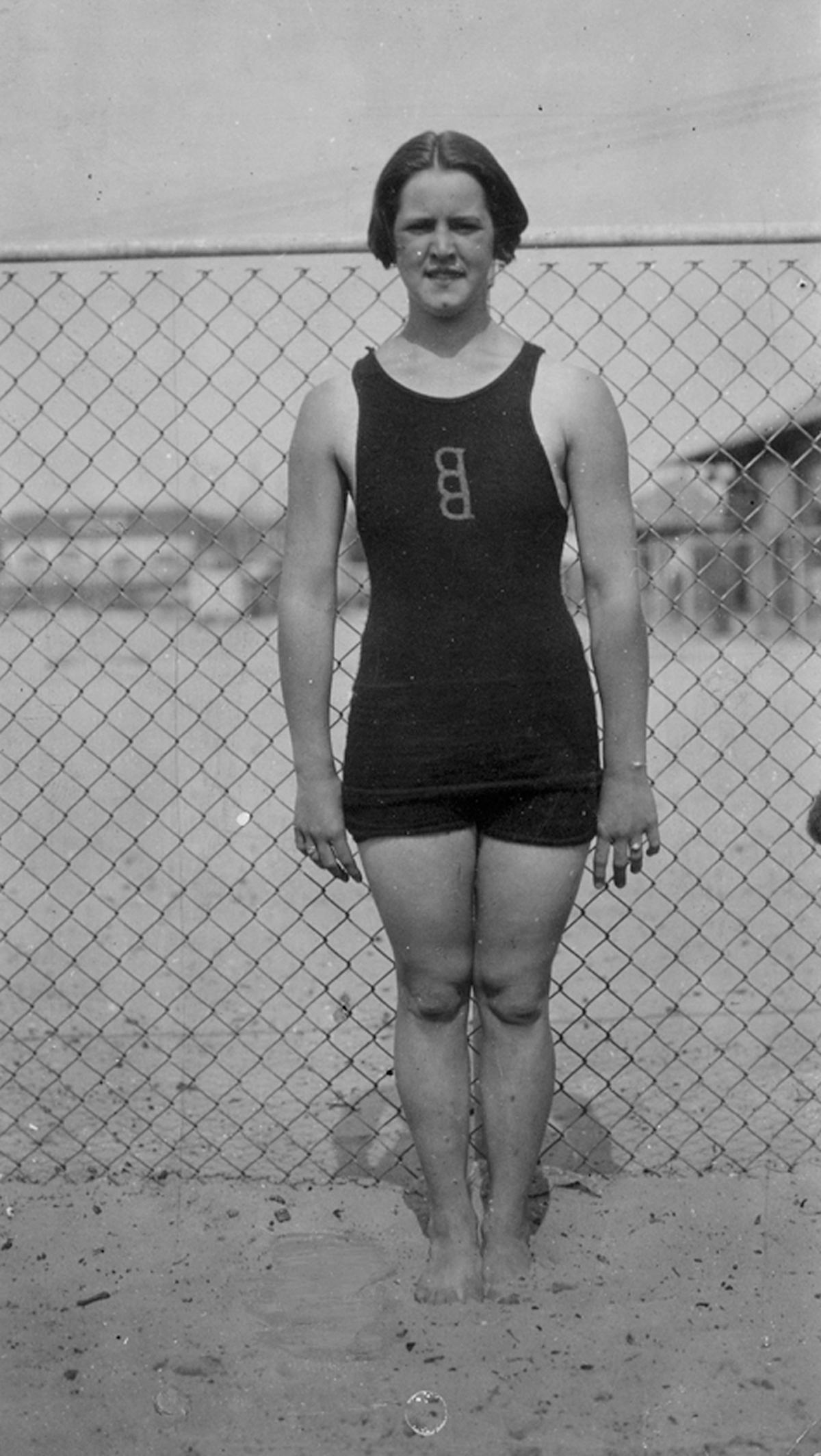

A smiling Trudy Ederle practices swimming in the English Channel.

Trudys Big Splash

O N THE MORNING OF A UGUST 6, 1926, an editorial appeared in the London Daily News about the rights of women to compete in and play sports. The editorial ended, Even the most uncompromising champion of the rights of women must admit that in contests of physical skill, speed, and endurance, they must forever remain the weaker sex. As residents of London read the paper over their morning tea, a young American woman named Trudy Ederle stood on the shore in France and looked out across the English Channel toward England, twenty-one miles away.

Although dozens and dozens of people had tried to swim the English Channel before, only fiveall menhad made it across. Swimming the Channel is one of the most difficult and dangerous athletic feats in the world. Even today, more people have climbed Mount Everest than have swum the English Channel. In 1875, Matthew Webb became the first person to swim the Channel, a feat that took him nearly twenty-two hours to accomplish. The speed record was held by the third person to swim the Channel, Enrique Tirabocci, who in 1923 made the crossing in sixteen hours and thirty-three minutes.

Although many had tried, no woman had ever swum the English Channel. A few had made it within a few miles of the opposite shore before bad weather, fatigue, and tides forced them out of the water, and many more quit after only a few hours in the water. In 1925, in fact, Trudy Ederle had tried to swim the Channel only to fail. Although she had been considered the greatest female swimmer in the world at the time, many observers thought that if Trudy could not swim the Channel, then no woman could.

Trudy disagreed and decided to try again. Now, just a few minutes after seven a.m., she adjusted her swimming goggles and stepped into the water. When the waves reached her chest, she took a deep breath, looked up at the sun peeking through the hazy summer sky, and whispered, God, help me. Then, with a big splash, she dove beneath the waves and started swimming.

Trudy was determined to succeed this time. She knew that a woman could swim the English Channel.

All she had to do was prove it.

In the summer of 1915, Trudys father, Henry, purchased a small cottage near the beach in Highlands, New Jersey. The Ederle family lived in New York City, where Henry owned and operated a successful butcher shop. Henry and his wife, Gertrud, thought their childrenHelen, age twelve; Meg, age ten; Trudy, age nine; and Emma and George, both toddlerswould enjoy spending the summers out of the city.

Highlands was beautiful. Trudy loved gazing out over the water, the sea breeze blowing through her light brown hair and the sun bringing out the freckles on her face. There were plenty of children her age to play with, but Trudy, who was partially deaf due to a bout with the measles a few years before, was a little shy. She sometimes couldnt understand what strangers were saying and occasionally felt embarrassed when meeting new people, so she followed her older sisters Helen and Meg around like a puppy. Nearly every day they all went to the beach together.

That was the problem. Helen and Meg knew how to swim. Trudy did not. When Helen and Meg went in the water, Trudy had to stay behind, playing alone in the sand and wading in the shallows.

It seems hard to believe today, but a hundred years ago, very few women knew how to swim, and few were allowed to compete in sports of any kind. When women went to the beach, they were expected to wear long-sleeved blouses and stockings that made swimming next to impossible. There were virtually no swimming pools with lifeguards, no groups like the YWCA that gave swimming lessons, and no girls swim teams or swim meets for young girls to compete in. Trudys sisters only knew how to swim because they had been taught the dog paddle and the breaststroke by their cousins when the family had visited relatives in Germany. Trudy had been too young to learn, and now she felt left out.

Henry Ederle, however, had a solution. One day he went to the beach with the girls and told Helen and Meg to get in the water. As Trudy stood on the beach, Henry took a strong piece of clothesline and tied it around her chest. He walked out onto a nearby pier and told Trudy to wade toward her sisters.

Trudy took a few cautious steps and suddenly her feet no longer touched bottom. As a panicked look came over her face and she began to sink, her father pulled on the rope, keeping Trudy on the surface. Then Meg and Helen urged her to paddle toward them.

At first Trudy did little more than thrash about while taking in great gulps of air before grabbing one of her sisters for support. But each time she let go and tried to swim from one sister to the other, she became a bit more confident and relaxed. Soon she could feel her body floating in the water. She forgot all about the rope and didnt even notice that her father had let it go slack.

Next page