Paul Robesons Unwavering Commitment

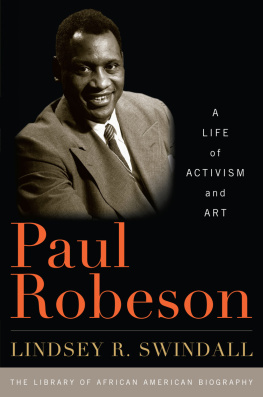

Paul Robeson, born in 1898, was a two-time All-American football player and a law-school graduate in an era that offered few opportunities for African Americans. He went on to win international acclaim as a singer and actor, breaking through barriers both on stage and in life itself. Robeson refused to compromise his integrity or to be told what African Americans could or could not do. When the United States government accused him of being a Communist, Robesons career as a singer and actor suffered.

In The Life of Paul Robeson: Actor, Singer, Political Activist, author David K. Wright tells the story of this exceptional entertainer who devoted his life to the causes of civil rights and equality. Today, Robeson is recognized for his astounding range of talents and his unwavering commitment as a champion of civil rights.

alive with insightful and revealing quotes.

School Library Journal

clear, crisp prose

Booklist

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

David K. Wright has written dozens of books, many of them about history or social studies. Mr. Wright has been a freelance writer for many years.

Image Credit: Library of Congress

Paul Robeson was an exceptional entertainer who devoted his life to the causes of civil rights and equality.

Peekskill, New York, in 1949 was a working-class village some forty miles north of New York City. Situated on the east bank of the Hudson River, the town was the hub of a busy summer tourist trade. Middle-class New York City residents owned vacation homes atop the hills and in the valleys around Peekskill. Some of the people who lived year-round in Peekskill did not like the vacationers. The visitors seemed to have more money than the locals; they worked in the dangerous, corrupt big city; many were Jews or other non-Christians; and several were Socialist or Communist sympathizers.

So when it was announced that Paul Robeson, the famous African-American actor, singer, and political activist, would give a concert in a Peekskill park, there was swift local reaction. The daily newspaper accused Robeson of aiding subversivesof helping people who want to overthrow the governmenteven though he had performed in Peekskill in the past. Veterans groups, such as the American Legion, wrote letters to the paper, stating that the entertainer was unwelcome in Peekskill. Virtually everyone else, from local politicians to the chamber of commerce, joined the disapproval. How could one man cause such a reaction?

Paul Robeson was no ordinary man. Born poor in a small town in New Jersey, he became an All-American football player, a superior college student, and one of very few African Americans at the time to graduate from law school. Added to these accomplishments were years of experience as a dramatic actor and a deep singing voice that could move even the least emotional listener to the brink of tears. He knew hundreds of old and new songs by heart, he spoke several languages, and he was famous throughout the world. Why were the people of Peekskill so upset at the prospect of a visit by such a talented performer?

The entertainer was a civil-rights activist in an era when comparatively few spoke up for the rights of minorities. He talked frankly, frequently stating opinions in public that most African Americans dared not utter. And he was well traveled, having performed on several continents. Besides the fact that he was black in a largely white town, Robesons numerous visits to and longtime familiarity with the Soviet Union angered many patriotic Peekskill people.

Peekskill residents knew little or nothing of Soviet society. But they, like many other Americans in those years, were against anything that tilted toward socialism or communism. One Socialist couple, who lived in New York City and owned a summer cottage near Peekskill, received phone threats and were called names as they shopped and as they worked in their yard. Some of the estimated twenty-five hundred people walking toward the concert were hit with rocks thrown by mobs of men as police idly stood by. A cross was set afire on a nearby hill.

Robeson, riding in a friends car, crouched on the floor to hide. The driver somehow got out of the line of cars headed for the concert, turned around, and returned to New York City. Arriving in Harlem, Robeson held a news conference. He said the Peekskill riot reminded him of Hitlerite Germany and asked federal authorities to look into the matter. He also promised to return to Peekskill for a concert one week later. Wisely, Robeson refused the offer of protection from Bumpy Johnson, Harlems most notorious gangster.

By the following week, everyone in Peekskill seemed to be against holding the concert. This time, eight thousand military veterans from all over New York State marched in protest in front of the Peekskill park. They yelled anti-black and anti-Semitic obscenities, telling union members and others, You came in but you dont get out of the park alive. Robeson took the stage at 4:00 P.M., flanked by fifteen burly union members acting as bodyguards. While he sang, roving unionists discovered two Peekskill men with rifles hiding in the area.

Whenever Paul Robeson sang, people listened. Even among the uneasy concert audience, the sound was magic. Deep yet somehow light, able to run up and down the scale, his voice effortlessly reached and held low notes only imagined by most male vocalists. A star in motion pictures, Robeson was generally recognized by the public during the pretelevision era. Millions had become enchanted at one time or another with his voiceone of the great voices of the twentieth century. Only baseball and boxing could draw a crowd comparable in size to that of a Robeson concert. Many in the big audience that afternoon cared little or nothing for politics. They just wanted to hear Paul Robeson sing.

The concert ended and the crowd started homeor made the attempt. Once again, the visitors were attacked. Rocks and bottles were thrown, and a number of people were bloodied. Police stood by watching. The star of the show was covered with a blanket and whisked from the scene in a fast-moving car. He was luckier than an estimated one hundred fifty concertgoers who required medical attention.

A grand jury later blamed Robeson and his audience for the confrontation. The grand jury may have been influenced by Governor Thomas E. Dewey, who ordered an investigation by some of the same people who had failed to keep order during the riot. The governor wanted to know if the concert had been scheduled for the purpose of disturbing the peace and whether the event was a Communist strategy to foment racial and religious hatred.

To understand all this, it helps to understand what America was like in 1949. President Harry S. Truman had only recently integrated the armed forces; African-American children were not allowed in many public schools; and major-league baseballthe national pastimehad permitted African-American players for only two years. Many white Americans were obsessed with the notion that African Americans were second-class citizens. Even those whites who did not necessarily dislike black people still generally ignored them. Paul Robeson, by virtue of his talent, physical size, and intelligence, was difficult to ignore.

Some people found Robeson especially frightening. Many white Americans believed Communists were trying to recruit African Americans who realized how unfairly they had always been treated in the United States. Though African Americans were much more concerned with justice than with revolution, Paul Robeson loomed large in the minds of people in Peekskill and elsewhere. Where had he come from, what had he accomplished, and where would events take him?