Steve Cowens was born in Sheffield in 1964, and he works and lives there today with his wife Debbie and their two children. He recalls going to his first game at Bramall Lane in 1970 and had his first season-ticket in 1974. Throughout the 80s and 90s, he was a recognised top face amongst the notorious and violent hooligan firm the Blades Business Crew. Today, with his life firmly away from his violent past, he has become a successful author, having penned the bestselling Blades Business Crew, a shocking diary of a hooligan top boy. He has followed this up with his recently self-published Blades BusinessCrew 2. In between, he has contributed to titles such as 30 Years ofHurt, Terrace Legends and Hooligans. He is currently writing his first fiction book.

He selects Tony Currie as his all-time favourite Sheffield United player and lists his hobbies as keeping koi carp and managing a successful adults football team in the Sheffield leagues.

I n Sheffield, its simple: you are either red or blue; a middle ground does not exist in our great city. Sheffields football divide, and the fierce rivalry that goes with it, has led to numerous arrests and jail sentences, countless injuries, near-fatalities and tragically even the death of an innocent United fan. The hatred between the two clubs has seen the use of weapons in battle including acid, petrol bombs, knives, bats and distress flares alongside the more common football weaponry taken from pubs, such as glasses, bottles and pool cues. Other cities sharing two football teams dont seem to have the intense problem that Sheffield has; in Liverpool, for instance, the Scousers can share the same pubs and ends on match days, but, in Sheffield, that is simply not possible. The Steel City divide has even been known to split families and ruin friendships.

But why do the Sheffield clubs hate each other with such a passion? Although both clubs fans share a mutual dislike for their rivals, in the 50s and 60s, some fans from both teams used to go to Hillsborough one week then Bramall Lane the following week. My granddad was one of those fans and, although he definitely went to watch Wednesday lose well, he hoped they would lose he really went to watch a game of football. Something changed during the late 60s and early 70s perhaps it was the explosion of gang culture, when teddy boys, skinheads, rockers and mods made it seem cool to be part of a gang, or maybe it was simply part of the social unrest amongst young men that was so evident at the time.

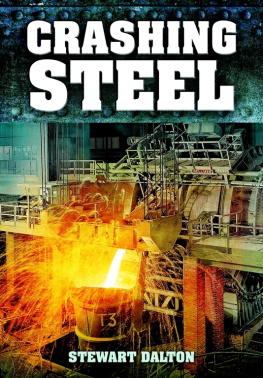

Sheffield became famous throughout the world in the 19th century for its production of steel; more notably it became the flagship of worldwide stainless steel production. This fuelled a tenfold increase in the local population during the Industrial Revolution. Sheffield gained its City Charter in 1893 and was officially titled the City of Sheffield. International competition inevitably saw a decline in local industry during the 1970s and 80s. This, coupled with the fact that Maggie Thatchers policies triggered the collapse of the national coal industry, lead to a reduced population in Sheffield.

Commonly known as the city of seven hills, Sheffield is surrounded by stunning countryside and the city itself has more trees per person than any other city in Europe. Sheffield is Englands fifth-largest metropolitan area with a population of 1,811,700, most of whom are from a working-class background, which helps make the citys people some of the friendliest, most welcoming people on our shores.

It has also bred football fans that will fight for their clubs territory and pride. This pride is often channelled into violence and derby day is not a place for the fainthearted. Even both clubs non-hooligan fans (some of the shirters) will forget their usual peaceful demeanour and fight for their clubs pride. The games themselves are not enjoyable occasions for either sides fans, as the fear and apprehension of losing make the games tense and fraught affairs. The workplace on Monday morning after a derby is always dreaded by the losing side as awaiting them are smug grins and smart comments, ingredients that make the actual game itself less than enjoyable. The depth of this feeling carries through to the players and staff of the teams. They know just how much winning or losing this fixture means to their supporters.

Both sets of fans refer to each other as pigs, a derogatory term which originated in the late 70s. Both sides can explain their reasoning for this: Wednesday say they call us pigs because Uniteds red and white shirts actually remind them of streaky bacon, while United fans argue that Hillsborough (Swillsborough) was actually built on a piggery, a fact backed up by local history books.

Local history society books which can be viewed at Sheffield Central Library state:

The Wednesday football club first played its games at the Olive Grove sports ground in Heeley before moving to a new stadium in the Owlerton district of Sheffield. The first ordnance survey maps mark the nearest building to the stadium as Swine Cottage. They also show another farm on Penistone Road, just south of where the north stand is situated which is thought to have been a large piggery [still is!]. Pork farming is thought to have been practised in the area since the early 1800s and did not cease until around 1900 when the citys rapid expansion put an end to pork farming in the area. At its height the Owlerton piggery, as it was known, provided work for more then 50 employees. Initial discussions about a new nickname soon began after Wednesdays arrival at Owlerton. In reference to their new home most of the clubs officials were in favour of the Owls, taken from Owlerton stadium. However, another suggestion was also very popular. In view of the areas strong tradition of pork farming, a popular grass roots alternative was the Pigs. Although the name Owls prevailed, many working-class supporters continued to refer to their team as the Pigs. A popular song of the time went, They may be Owls to some, but theyll always be Pigs to me. This song was performed in music halls across South Yorkshire. As late as the 1920s and 30s, fans used to welcome their team on to the field with characteristic grunting sounds [they still do that!]. This peculiarity was once referred to by BBC commentator Edward Milburn, who famously described Hillsborough as a sea of grunts, moments after the Wednesday won the First Division title in 1932.

These facts show why and who the pigs are in Sheffield but, of course, Wednesday fans will never let the facts get in the way of their piss-poor argument about the colours of our shirts.

Sheffield itself has areas where each club has strongholds, some of which are actually on each others doorsteps and invasions into hostile territory have often ended in conflict. Be it a one-on-one fight outside a local pub, a 10-on-10 youth brawl on the back streets of town or hundreds of hooligans seeking conflict on derby day, the rivalry will often manifest into violence. One things for sure, after 40 years of trouble between the two sides, the city is as divided as ever when it comes to football.