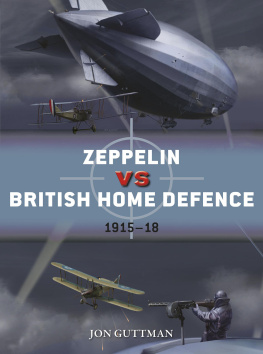

Zeppelin caught in the searchlights during a raid on London, 1915.

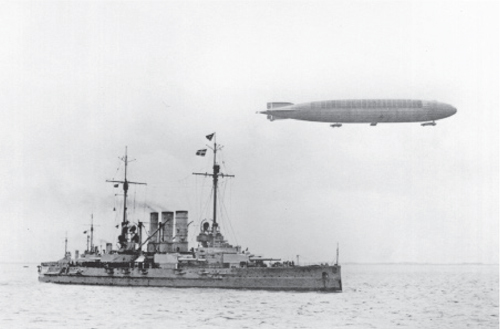

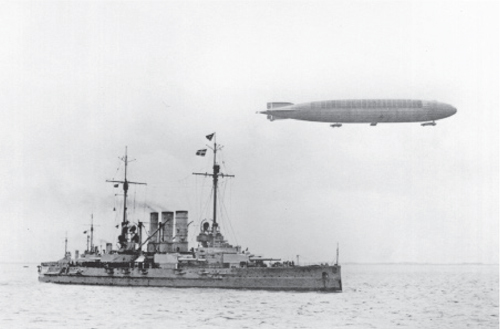

Zeppelin crossing the North Sea to bomb Britain, with the cruiser Ostfriedland in the foreground.

The National Archives; Imperial War Museum, London and Duxford; RAF Museum, Hendon; The Commonwealth War Graves Commission; Kath Griffiths, Norfolk Library and Information Service Heritage Library; Dr John Alban, Susan Maddock and Freda Wilkins-Jones at The Norfolk Record Office; Great Yarmouth Library (Local Studies); Alan Leventhall, Kings Lynn Library (Local Studies); BBC Radio Norfolk; The Fleet Air Arm Museum, Yeovilton; Sue Tod, Felixstowe Museum; The Association of Friends of Cannock Chase; The Long Shop Museum, Leiston, Suffolk, Woodbridge Museum; Dr Paul Davies and Andrew Fakes of Great Yarmouth Local History & Archaeological Society; Reverend Barry K. Furness, Smallburgh Benefice; Geoffrey Dixon; Scouting archivist Claire Woodforde, Norfolk Family History Society; Kevin Asplin; Helen Tovey, Family Tree Magazine ; Dr Stephen Cherry, Stewart P. Evans, Mike Covell, Amanda Hartmann Taylor and my loving family.

CONTENTS

Came the Thing they were sending us, the Thing that was to bring so much struggle and calamity and death to the earth. I never dreamed of it then as I watched; no one on earth dreamed of that unerring missile.

H.G. Wells, War of the Worlds (1897)

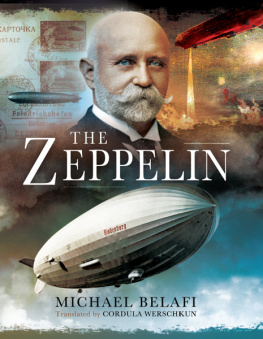

Since the first flight of Count Ferdinand von Zeppelins LZ-1 over Lake Constance (Bodensee) on the Rhine on 2 July 1900, the vast size (128m long) of these lighter-than-air craft prompted feelings of awe and, as the reality of their military potential was realised, they were increasingly regarded as an ominous presence in the sky, especially by people in the European countries surrounding the German Empire.

In a world which had witnessed unthinkable progress in industry and engineering throughout the nineteenth century, there were those who feared the technology of military development had gone too far. Authors contemplated the machinery of war with fascination, the most enduring of these being H.G. Wells The War of the Worlds , in which an invasion and brutal occupation by extra-terrestrials was unstoppable by even the most modern of our weaponry. Add to this the tenor of over sixty books and numerous magazine articles describing invasions of Great Britain by foreign powers published between 1871 and 1914. The seminal Battle of Dorking by George Tomkyns Chesney, originally published as a story in Blackwoods Magazine in 1871, tells of a fictional German attack and landing on the south coast of England that had been made possible after the Royal Navy had been distracted in colonial patrols, and the army by an insurrection in Ireland a situation that was to have resonances in the Zeppelin air raid and bombardment of Lowestoft on the evening of 24/25 April 1916.

The distrust and perception of anti-British feeling and the sinister machinations of the German race continued to feature regularly in the popular press, and books too, such as The Riddle of the Sands (1903), in which Erskine Childers weaves a tale of two young amateur sailors who battle the secret forces of mighty Germany. Their navigational skills prove as important as their powers of deduction in uncovering the sinister plot that looms over the international community.

Anglo-German relations were strained further after the launch of the revolutionary HMS Dreadnought the first big-gun, turbine-driven, iron-clad battleship in 1906, when the Germans started building their own warships, akin to and rivalling the pride of the British fleet. To many British observers this meant nothing less than a challenge to the maritime supremacy of Great Britain. This fire was further kindled by Anglo-French journalist and writer William le Queux, who produced such best-selling titles as The Invasion of 1910 (1906) and Spies of the Kaiser (1909). He made no secret that his books were fiction, but claimed that they were based on his own secret knowledge and the insight he gained from his connections within the European intelligence community.

In the spring of 1909, newspapers had columns of reportage about the advances, and planned advances, of the parameters of manned flight. In May 1909, John Moore-Brabazon became the first resident Englishman to make an officially recognised aeroplane flight in England. The previous year, Alfred Harmsworth (Baron Northcliffe), proprietor of the Daily Mail newspaper, had put up a reward of 1,000 for the first flight across the English Channel, a feat which was achieved by Louis Bleriot on 25 July 1909. So, no aircraft had crossed the English Channel before July 1909, but after reports of successful distance trials of Zeppelins in Germany, in the climate of anti-German fears many considered that the purpose of these monstrous creations could only be a sinister one and worried how long it would be before they appeared over Britain.

Curiously, in March 1909, Police Constable James Kettle was walking his beat on Cromwell Road in Peterborough, Cambridgeshire, when, upon hearing the steady buzz of a high-powered engine was caused to look up, where he saw a bright light attached to a long oblong body outlined against the stars as it crossed the sky at high speed. His report was met with interest from national newspapers, but no doubt fearing the panic such accounts could create, a senior police officer was sent to front the explanations. Kettle, it was claimed, had simply been mistaken; the whirring he had heard was attributed to the noise from the nearby co-operative bakery, and the object in the sky was explained as a Chinese lantern attached to a very fine kite flying over the neighbourhood of Cobden. The speed Kettle had mentioned was just brushed off as a little poetic touch for the benefit of you interviewers.

However, more sightings of these mystery airships began to occur across the country, and by May 1909 newspapers across Britain were full of accounts of unexplained airships which had been seen and heard traversing the night sky over Great Britain, at locations as far apart as Wales and Suffolk. In one notable instance, on Friday 7 May a long sausage-shaped dirigible balloon was spotted over New Holland Gap, 1 miles from Clacton in Essex. On a spot over which the airship had passed was found what was described as a stout ovoid dark grey rubber bag, between 2ft and 3ft in length, enclosed in a network mesh, with a stout steel rod passing through the centre of it and projecting about 1ft from each end. One end of the rod is capped with a steel disc resembling a miniature railway-waggon buffer. It was thought that the object was some sort of fender designed to break the contact of a descending aerial machine with the earth the bag was stamped Muller Fabrik Bremen.

On 14 May, the Daily Express s Berlin correspondent had reported:

It is admitted by German experts that the mysterious airship which has been seen hovering over the eastern coast of England may be a German airship. England possesses no such airship, and no French airship has hitherto sailed so far as the distance from Calais to Peterborough. On the other hand, the performance of several German airships, including the Gross airship, which has made one voyage of thirteen hours, would render it possible for them to reach the English coast. At the same time it is improbable that the German airship seen above England ascended from German soil. An aerial voyage to the English coast would still be a dangerous and formidable undertaking even for the newest airships

Next page