Harry Benson

SCRAM!

The Gripping First-hand Account of the Helicopter War in the Falklands

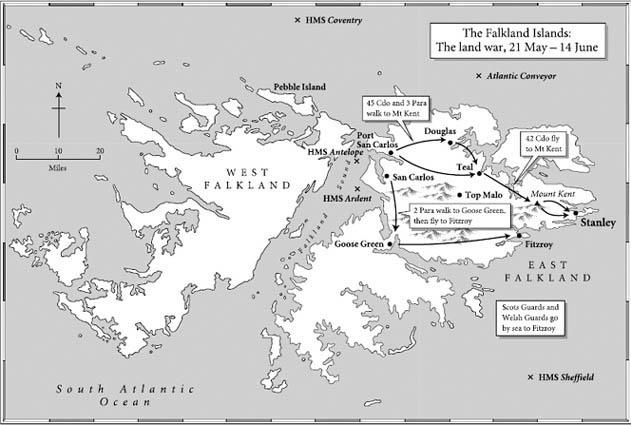

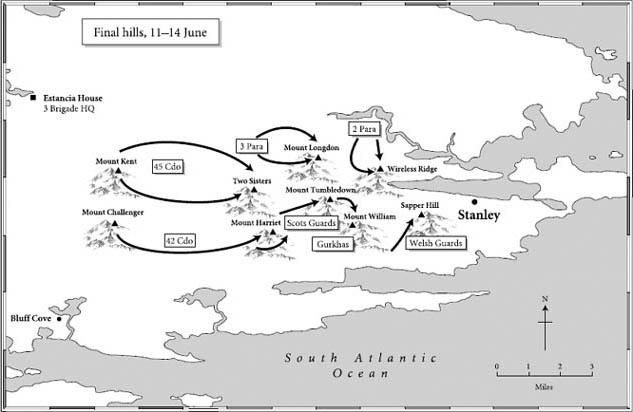

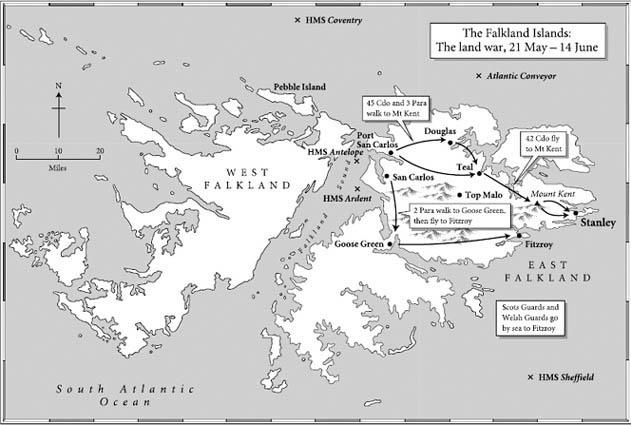

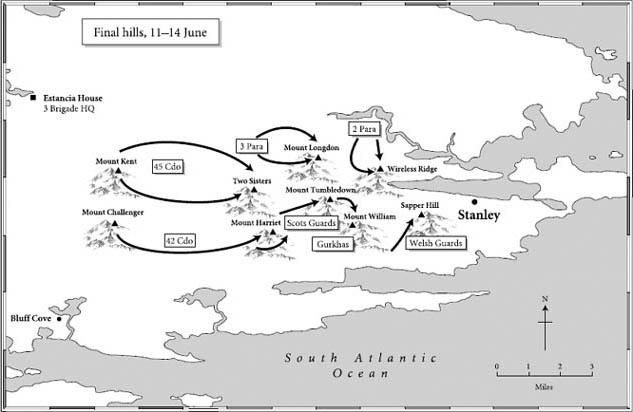

The final land battles of the Falklands war took place in two distinct phases. Night of 11/12 June: Longdon, Two Sisters, Harriet. Night of 13/14 June: Tumbledown, Wireless Ridge and Sapper Hill.

Julian Thompson

Commander 3rd Commando Brigade in 1982

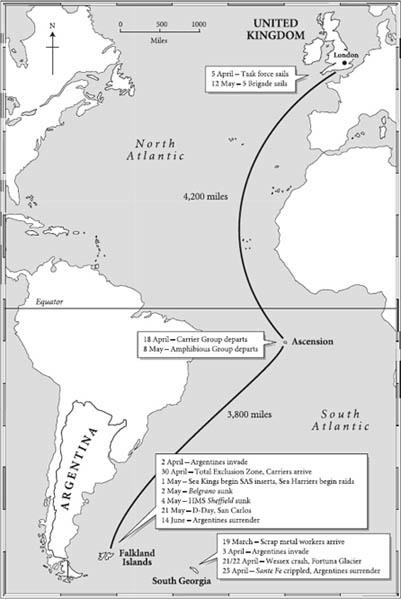

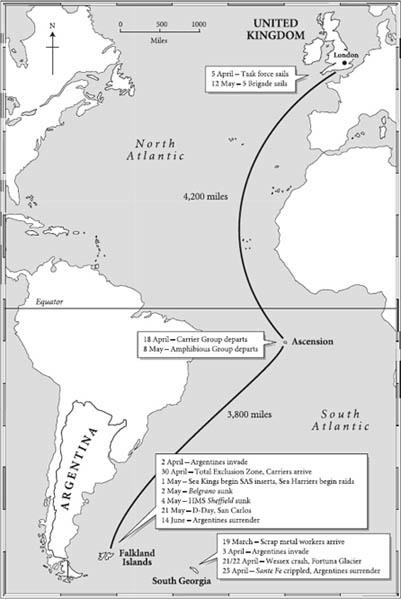

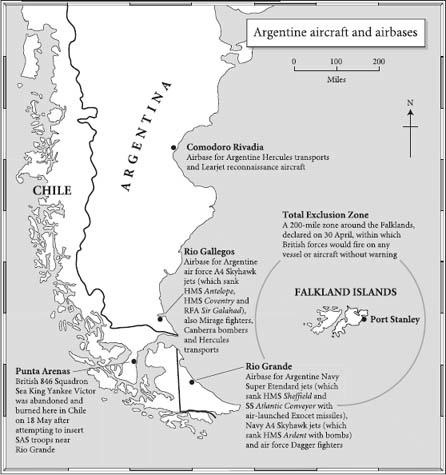

Harry Bensons aptly named Scram! is the first account to be written about the junglies part in the Falklands War of 1982. The junglies being the name for the Royal Navy troop lift helicopters, dating back to the campaign in the jungles of Borneo in the 1960s. Back then, the Fleet Air Arm helicopter aircrews made a name for themselves as can do people a reputation that they more than upheld in the Falklands War. Scram, broadcast over the helicopter control radio net during the Falklands War meant take cover from Argentine fighters. This call was a regular feature of life down south, especially during the first six days after we landed while the Royal Navy fought and won the Battle of San Carlos Water; arguably the toughest fight by British ships against enemy air attack since Crete in 1941. As the Argentine fighter/bombers came barrelling in I would watch heart in mouth as the junglies headed for folds in the ground, remaining burning and turning until the enemy had left. Sometimes there was nothing for it but for them to keep on flying, especially if the helicopter in question was carrying an underslung load; or had just lifted from a ship well out in San Carlos Water, with nowhere handy to hide.

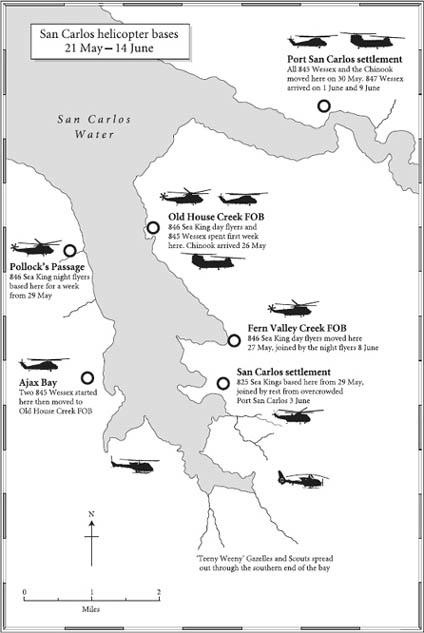

Today there is a road network in East Falkland. In 1982 there were no roads outside Stanley and a rough track from Fitzroy to Stanley. Every single bean, bullet, and weapon had to be flown forward from where it had been offloaded from ships unless it was carried on the back of a marine or soldier, or by the handful of tracked vehicles capable of negotiating the ubiquitous peat bog that along with stone runs and dinosaur-like spine backed hills constituted the Falklands landscape. Likewise every casualty had to be flown back. Without the junglies there would have been no point in us going south to retake the Falklands; we would have got nowhere.

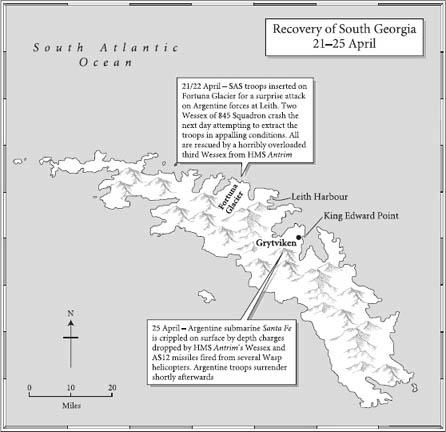

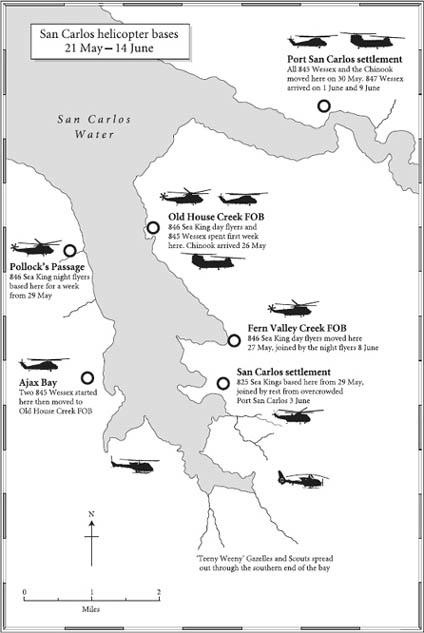

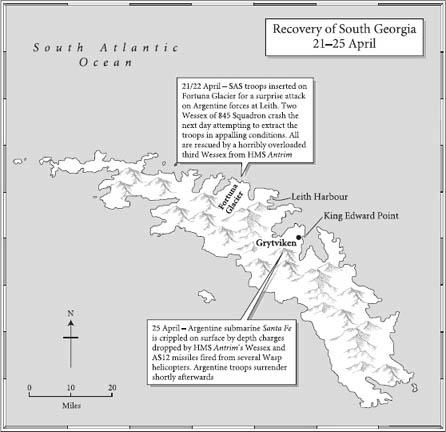

I am glad that Harry Benson has given space to tell of some of the activities of the non junglie choppers. He relates in some detail the story of the epic rescue of the SAS from the Fortuna Glacier in South Georgia by HMS Antrims anti-submarine helicopter; a pinger to the junglies. What the SAS thought they were doing up there is another matter, and my opinions on the matter are best left unsaid. Harry Benson also devotes space to the activities of the 3rd Commando Brigade Air Squadron; the gallant 3 BAS, or to some TWA (standing for Teeny Weeny Airways) 3 BAS suffered the highest casualty rate and was awarded the most decorations in proportion to its numbers of any organisation on the British side in that War. The outstanding support given to the land forces by the only RAF Chinook to survive the sinking of the Atlantic Conveyor is also given due recognition.

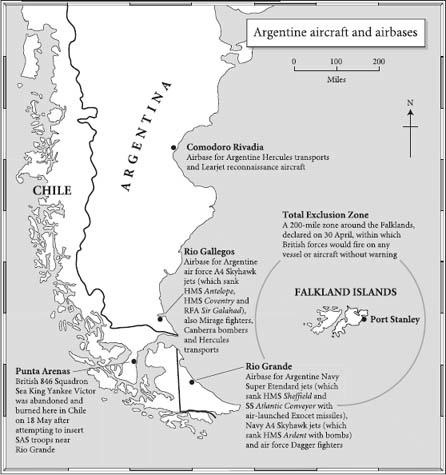

We went south with far too few helicopters initially. Those we had were flown every hour they could be; often with bullet holes in fuselages, red warning lights on in cockpits denoting malfunctioning equipment; breaking every peacetime rule. One of the 3 BAS Scout helicopters had a bullet hole in the tail section patched with the lid from a Kiwi boot polish tin. Todays health and safety nerds would have an apoplectic fit. The aircrews worked themselves into the ground. In wartime you should have at least one and a half times the number of aircrew as you have aircraft. Aircrew fatigue will strike long before the aircraft wear out. We did not have this ratio of crews to aircraft. The imperatives of warfighting had long been forgotten. While the rats in the shape of politicians and civil servants had gnawed away at the manpower of the Fleet Air Arm along with everything else connected with defence. Fighting 8,000 miles from home was not the war we had prepared for in the long years of the cold war. But you rarely fight the war you think you are going to fight; this had been forgotten too. Fortunately for those of us fighting the land campaign, none of this fazed the junglie aircrew; our lifeline. They got on with the job, often flying in appalling weather, in snow blizzards both by day and night, with low cloud concealing high ground, and often along routes easily predictable to the enemy, with the ever-present threat of being bounced by enemy fighters in daylight; most deadly of all being the turbo-prop Pucara which with its low speed was far more dangerous to a helicopter than a jet.

The story of the deeds of the junglies in the Falklands War is well overdue. I am delighted that it has been written at last.

A great deal has been said and written about the Falklands War: the task force, the Sea Harriers, the Exocets, the Paras, the Marines, the amphibious landings. But what is so extraordinary is how little is known of the exploits of the young helicopter crews, my friends and colleagues the junglies who made much of the war happen. Junglies are Royal Navy commando pilots, a throwback to the 1960s when British helicopters flew over the jungles of Borneo. Days after the Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands in April 1982, a British task force was deployed with junglie crews spread throughout the fleet. These squadrons, with their Sea King and Wessex helicopters, flew most of the land-based missions in the war. Yet almost nothing has been written about our exploits.

It wasnt until an informal reunion in June 2007 that I realised this. A bunch of us former junglies had arranged to meet in a pub in Whitehall the night before we were to parade down the Mall for the formal twenty-fifth anniversary celebrations. I hadnt seen many of these guys in years. Seeing old friends was an emotional moment at first. But then the beer did its work and we were off, armed with a licence to tell each other our war stories.

What was so amazing that evening was not just that there were so many fantastic stories, but that none of us knew what the others had done during the war. In many cases, the stories were coming out for the first time. I sat transfixed as I heard about the helicopter missile strike on Port Stanley. And although I knew about the helicopter crashes, I had never heard any of the detail first hand. I knew little of the dramatic rescues from burning ships and even less of the harrowing story of being on the wrong end of an Exocet strike. I had absolutely no idea that anybody had gone head to head with an Argentine A-4 Skyhawk or the dreaded Pucara, or been strafed by a Mirage and survived. None of us had spoken about it. Until now.