Death in the City of Love

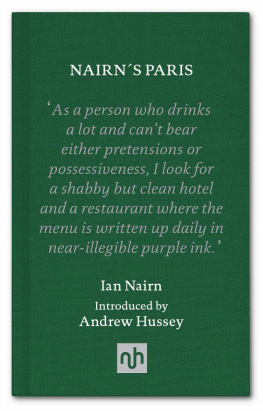

Paris, city of lights, city of love, city of magic, city of art, city of death. Some twelve million people call the Paris metropolitan area home including about two and a quarter million within Paris 20 arrondissements. Millions more call Paris their permanent home, including upwards of seven million in the in the Montparnasse district.

The Paris basin area was first inhabited around 4200 B.C. Then in around 250 B.C., a group of people known as the Parasii established a settlement that would stay. The Romans moved into the area in 52 B.C. and founded a settlement on the left bank of the Seine named Lutetia Parisiorum.

During Roman times, the Roman rulers applied their burial customs to the populace dictating that burials were to occur outside the town limits. The Law of the Twelve Tables stated, it is forbidden to burn or inter a corpse within the walls. The citizenry largely ignored that edict. As the years ticked on and Roman influence waned and was supplanted with Christian and Catholic tradition, most Parisians elected to bury around the perimeter of parish churches in areas known as Gods Acres. Wealthy and influential church officials were often buried within the walls and floors of the church. And in the words of modern-day realtors, it was location, location, location. The common belief was that the closer the body was to the altar, the better chance the deceased would be inched towards the heavens with the parishioners prayers. By the end of the eighteenth century, all of Paris fifty-two parish churches and their adjoining burial grounds were full to bursting with bodies. When all available space with the walls, floors and interior of the church was filled, even the elect and the well to do had to settle for ground burial. The dead were buried ten deep, but still there was not enough room, so they were often dug up and their bones piled high in gallery arcades and charnel houses surrounding the cemeteries. Cremation was not an option, since the Catholic Church expressly forbade it. No body = no resurrection.

Pre-Lachaise Cemetery

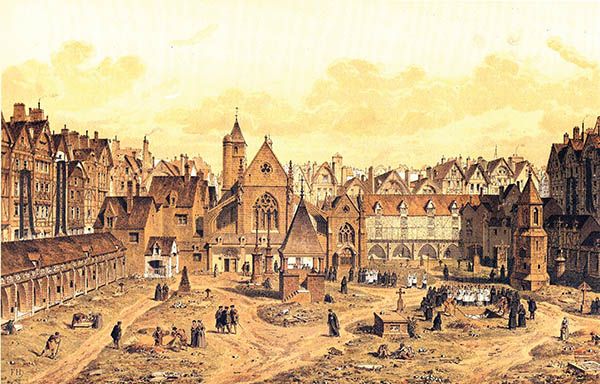

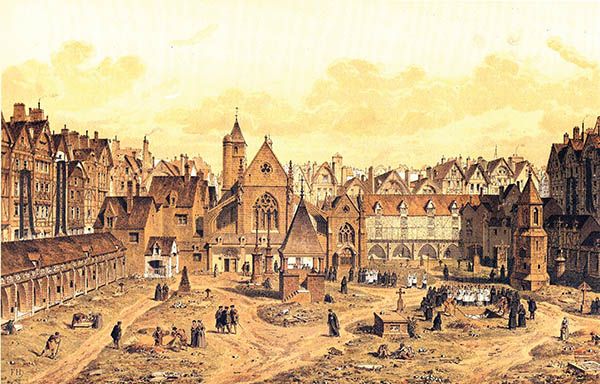

The most famous, or better yet, infamous, of these burial grounds was the Cemetery of the Innocents. The Cemetery of the Innocents (Cimetire des Innocents) started as a small churchyard cemetery for the Church of the Holy Innocents around the twelfth century (the area had been used as a burial ground dating to the Roman times). A market and the cemetery existed side by side in a sort of mutual harmony. The cemetery was good for the markets business since the steady stream of burials and funeral processions brought people to the market. The market was good for the cemeterys business since it was an attractive location and the Catholic Church profited from burial fees. Eventually the cemetery expanded and began accepting burials from sixteen different parishes, the morgue, the prison and Paris largest hospital, the Htel-Dieu. Plagues in 1348, 1418 and 1466 brought even more bodies. Bodies were typically buried in open pits that held about 1,500 corpses each. Even with various expansions, the cemetery was only about 400 feet by 200 feet. At one point, the ground level was raised to accommodate more bodies. Later, the bodies were dug up and placed in arcades around the cemetery. By the middle of the eighteenth century, around two million Parisians had been buried in the cemetery. Finally, in 1763 Parliament opened an inquest to figure out what to do with the ever-expanding cemeteries. Alas, the theological interests quashed the inquest since the church made money extracting funeral and burial fees.

By 1780 the burial crisis came to a head when a basement wall in a building next to the Cemetery of the Innocents collapsed, sending upwards of two thousand bodies in various states of decay tumbling into the basement. It would take another six years before the government and the church could agree on how to properly move the bodies to a new location while preserving the tenets of the church concerning death, burial and the afterlife. The other problem, of course, was, despite the ban on burial, Parisians kept dying. That problem initially fell upon Napolon Bonaparte who delegated it to Nicolas Frochot who established the first new cemeteries in Paris. Those cemeteries and Pre-Lachaise (Cimetire du Pre-Lachaise) in particular became the template for all future cemeteries, not only in Paris but also over much of the world.

Cemetery of the Innocents

Place Joachim du Bellay, site of the Cemetery of the Innocents. Finished in 1550, the Fountain of Innocents is the oldest monumental fountain in Paris. 48 51' 38.17" N 2 20' 52.43" E

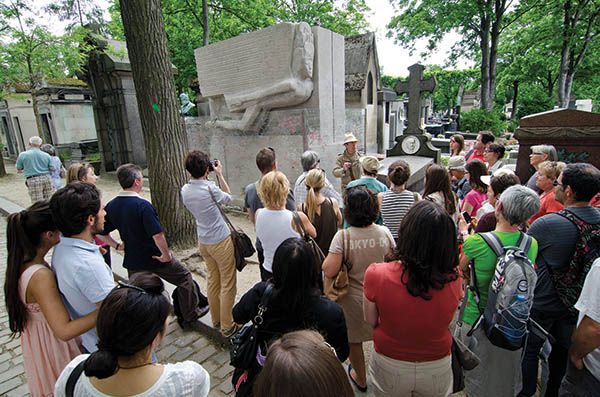

In what seems like a clever irony, cemeteries are not for the dead. The dead, of course, could care less. Cemeteries are for the living. They are the place we go to remember and to honor the past and those who created it. We go to experience our own mortality. We go to see fantastic art and architecture. We go to get close to celebrities and history makers. And cemeteries arent the only places well go to remember. Well go to Washington, D.C., to view a long black granite wall and touch the names of those who died in the Vietnam War. Or well journey to New York City to touch the names of the victims of 911. Visitors to Paris may wish to visit a makeshift memorial above a tunnel beneath the Pont de lAlma where on August 31, 1997 a twentieth-century princess met her end.

The cemeteries and monuments in Stories in Stone Paris cut across a wide swath of the last two hundred years of Paris history. It is, of course, quite impossible to list every important person or monument. So, while you are going from monument to monument, stop and linger at others along the path and make some discoveries and explorations on your own. Cemeteries and memorials are places for us to truly understand that our time in this realm is fleeting. Honor those places. Honor your life and those around you.