Margaret Lazarus Dean

LEAVING ORBIT

Notes from the Last Days of American Spaceflight

To Elliot, and the future

Lovell: Well, how about lets take off our gloves and helmets, huh?

Anders: Okay.

Lovell: I mean, lets get comfortable. This is going to be a long trip.

Transcript of Apollo 8, first mission to lunar orbit, 1968

It is easy to see the beginnings of things, and harder to see the ends.

Joan Didion, Goodbye to All That, 1968

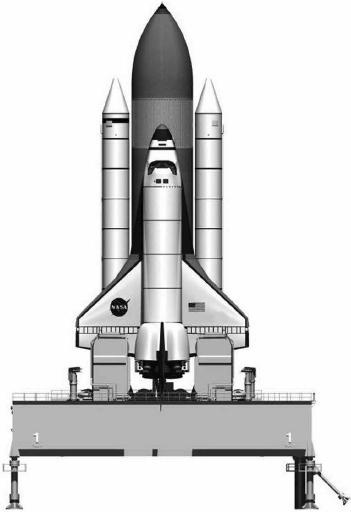

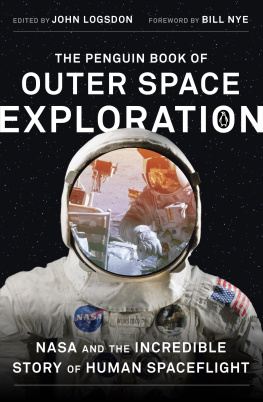

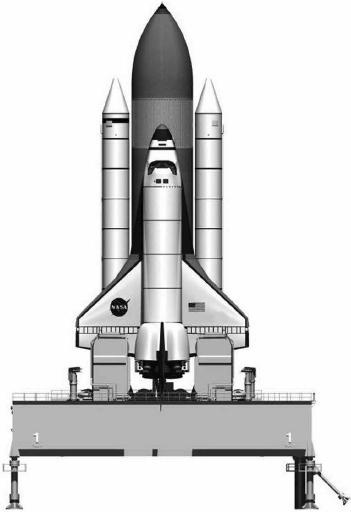

Saturn V

Space Shuttle

Credit: NASA

The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, has a grand entrance on Independence Avenue, a long row of smoked-glass doors set into an enormous white edifice. Most of the buildings nearby are marble or stone, neoclassical, meant to appear as old as the Capitol and the Washington Monument, which flank them. The Air and Space Museum, completed in 1976, is an exception: it is meant to look ultramodern, futuristic, which is to say it looks like a 1970s idea of the future.

I remember pulling open one of those doors as a child, the air-conditioning creating a suction that fought me for the doors weight. When I was seven, in 1979, I first visited the Air and Space Museum with my father and little brother, and for years of weekends after. This was what we did now that my parents had officially separated, now that our court-ordered visitation arrangements gave our weekends a sense of structure they had never had before. Divorce is supposed to be traumatic for children, and as time went on ours would become so, but not yet. For the time being, there was something festive about leaving our normal old lives and going on an outing with our father. Where we went each weekend was Air and Space.

We stepped over the threshold and into the chilled hush of the interior, one enormous room open many stories high to reveal old-timey relics of flight hanging by invisible wires from the ceiling. I knew the names of the artifacts long before I understood what they had done: The Spirit of St. Louis. The Wright Flyer. Friendship 7. As a child, I was vaguely aware that everything was out of chronological order, but I wasnt sure what the correct order was. The artifacts were simultaneously elegant and crude, all of them covered with an equalizing layer of dust. I liked to hear the sound of my fathers voice, and I liked the way he explained to me things that most adults would assume were beyond my comprehension. My father was in law school, in the midst of switching careers, but being with him at Air and Space revealed how much he missed the math and engineering he studied most of his life, all the way through a PhD from MIT. He told me about orbits, gravity, escape velocity, the Coriolis effect. I tried to understand because I wanted him to think I was smart.

I was often bored in Air and Space, but I was often bored in general: boredom was a natural state for a dreamy little kid often left, benignly, to her own devices. At home and at school I read a lot, stared out windows blankly, and took in whatever music was floating through my fuzzy consciousness: Bachs Brandenburg concertos at my fathers apartment, the Supremes and the Pointer Sisters in my mothers car, Top 40 radio at my schools extended day program where those of us with working parents went after class: Rock with You. Do That to Me One More Time. Hit Me With Your Best Shot. Another Brick in the Wall.

Even at its busiest, Air and Space was always hushed, the only sound the faraway murmurings of tourists who walked reverently past exhibits silent behind their glass. I looked at the exhibits. In the past, apparently, men ate food from toothpaste tubes while floating in space: here was one of the tubes, displayed in a case. In the past, men walked on the moon wearing space suits. Here was one of the suits, moon dust still ground into its seams. Here were the star charts the astronauts used to find their way in spacesometimes they had to do the math themselves, in pencil, and I could see their scrawled figures in the margins. Here was a moon rock, brought back to Earth in 1972, the year I was born. People lined up to touch the relic. At Air and Space, spaceflight seemed like an experience both transcendently pleasurable (the amniotic floating in zero G, the glowing blue world out the window like a jewel in its black velvet case) and also gruelingly uncomfortable (the cramped capsules and stiff space suits). No way to bathe and no privacy, the merciless nothingness just outside the spaceships hastily constructed hulls.

In the lobby was an artifact that at first looked like nothing more than a large charcoal-gray circle, thirteen feet in diameter, on a low platform in the middle of the room, encased in glass. That circle was the base of a cone-shaped object, which turned out, when you walked around it, to be the crew capsule from Apollo 11. The museums curators could have chosen to place the capsule on a pedestal, or to hang it from the ceiling, like so many of the others, but instead its position was unassuming, out on the floor where people could examine it closely. My father and brother and I did just that, and on the other side we encountered an open hatch revealing a beige interior with three beige dentist couches lying shoulder to shoulder facing a million beige switches.

My father spoke behind me. Three astronauts went to the moon in here. I noted the reverence in his voice. It took them eight days to get there and back.

Mmm, I said noncommittally. This made no sense, this claim that three full-grown men had crammed themselves into this container the size of a Volkswagen Beetles backseat, even for an hour. This story seemed like a misunderstanding best politely ignored.

Neil Armstrong sat there, my father said, pointing at the couch at the far left. Michael Collins sat here. And Buzz Aldrin sat here.

For the rest of my life, the syllables of those three names would call up for me this moment, those couches, that tiny cramped space, the way the capsule, then only ten years old, felt both futuristic and outdated at the same time. Already the moon landings were fading into history; already my father had in his apartment a computer much more powerful than the one carried on board this spacecraft. For a child in 1979, the moon landings seemed largely fictional, an event our parents remembered from their own youth and liked to tell us about, and therefore boring and instructive. Yet standing in Air and Space I found there was something pleasing about the contradictions contained in that capsule: the cozy utility of its interior combined with the risk of death just past the hull. There was something about all this I loved in a way I couldnt have described, still cant. The closest I can come is to say that this was the first time I understood that, despite their long and growing list of appalling limitations, grown-ups had at least done this: they had figured out how to fly to space. They had, on at least a few occasions, used their might and their metal machines to make a lovely dream come true.

As I grew up, we kept going back. On a visit in 1985, we watched The Dream Is Alive, a film shot by astronauts on three different space shuttle missions, in the museums IMAX theater. The camera pans around the empty cockpit of the space shuttle Discovery, where along the far wall, two large bright blue bundles float horizontally. The camera approaches and finds sleeping people. One of them is a woman of surprising beauty, her dark curly hair floating about her. This is Judith Resnik. She sleeps, or pretends to sleep; her long lashes rest on her cheeks. Her tanned arms linger in the air before her, and the look of peace on her face is captivating. Judith Resnik sleeps in space.

Saturn V

Saturn V Space Shuttle

Space Shuttle