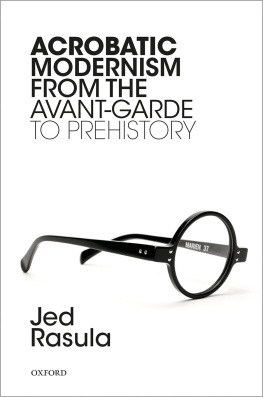

MORE ADVANCE PRAISE FOR DESTRUCTION WAS MY BEATRICE

An informative, lively, and entertaining narrative of Dada, a veritable biography of an enormously influential art movement on the 100th anniversary of its birth.

Francis M. Naumann, curator and author of The Recurrent, Haunting Ghost: Essays on the Art, Life and Legacy of Marcel Duchamp

A readable narrative that rejoices in the spirit of Dadas fleeting existence, never alighting on the precast definitions that have often shackled previous explanations. Rasula brings the Dadaists to life in vivid accounts of their interactions, aspirations, mishaps, and triumphs.

Timothy O. Benson, Curator, Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Copyright 2015 by Jed Rasula

Published by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, New York, New York 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Designed by Cynthia Young

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rasula, Jed.

Destruction was my Beatrice :

Dada and the unmaking of the twentieth century / Jed Rasula.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-465-06694-0 (e-book)

1. Dadaism. I. Title.

NX456.5.D3R37 2015

700'.41162dc23

2015004226

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

TO JERRY ROTHENBERG, PIERRE JORIS, AND ALL MY FELLOW TRAVELERS IN DADA

CONTENTS

Z urich in February is deep into winter. The street has a dusting of fresh snow on accumulated layers that crunch underfoot; cheeks and noses of pedestrians glow in the mountain cold. In the old bohemian district, a block from the river that feeds into the lake from the north, the door opens at number 1 Spiegelgasse (Mirror Street: what a name), emitting a dense cloud of tobacco smoke. The year is 1916, and the place is Cabaret Voltaire.

The space is crammed with tables, which are full to bursting; theres barely seating for fifty, and the performance platforms a tight squeeze. The wallspainted black, under a blue ceilingleer with grotesque masks and artworks by Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, and August Macke.

A slightly pockmarked, emaciated man plays honky-tonk piano to set the mood. After crooning a tender ballad, a slender, faintly wasted-looking ingenue abruptly lurches into a ribald number. Then, with the demeanor of a madonna, she does the splits. A few others join her for a vaudeville skit, followed by a recitation from Goethe, Germanys Shakespeare and Ben Franklin rolled into one. A short young fellow with a monocle delivers a Maori tribal spell (Ka tangi te tivi / kivi / Ka tangi te moho), spinning and wiggling like a belly dancer. A pianist and cellist indulge in a heartfelt lyrical movement from a forty-year-old Saint-Sans sonata. Then three of the performers pair up, knocking out a poem for three voices in three languages (French, German, English), babbling simultaneously. Students from Rudolf Labans nearby academy of modern dance stomp out an Expressionist number. A menacing, sneering figure glares at the audience as he snarls and roars his way through one of his Fantastic Prayers, while pounding a big bass drum and swishing a riding whip. The gaunt pianist, back at the keyboard, launches into a Hungarian Fantasy by Franz Liszt.

Its a variety show, after all, and the audience gets bits and pieces of what theyd expect in the usual venues. But here its differentvery different. There is a palpable fever in the air at Cabaret Voltairean electric sensation that persists for the five months the cabaret is open. And by the time it closes down, this primordial environment has borne an offspring.

They call it Dada. Who named it will remain permanently in dispute. An entry in Hugo Balls diary indicates only that he had discussed the word with Tristan Tzara on or before April 18, 1916. All thats certain is that the word emerged by chance from a French dictionary. In French it can mean hobbyhorse and nursemaid. Researching the word, the cabarets artists are delighted to find dada also means the tail of a sacred cow for an African tribe, and in certain regions of Italy it indicates a cube and a mother. For the Rumanian artists who congregated at the cabaret, it was a word they said to each other all the time in conversation: da, da, meaning yes, yes. A perfect word, they decided, for a mood coming over them. But what does it mean?

O f making many books there is no end, the book of Ecclesiastes observes. The same could be said of definitions of Dada, the most revolutionary artistic movement of the twentieth century. Dada is daring per se. Self-kleptomania is the normal human condition: thats Dada. Dada is the essence of our time. Dada reduces everything to an initial simplicity. These are among the characterizations of Dada by Dadaists themselves. But because Dada arose in defiance of definitionsridiculing complacency and certitudethe cascade of definitions it has spawned should be taken with a grain of salt. Those grains accrue, becoming heaps, of which it could be said, there is no end.

The true dadas are against DADA, observed one of the cabarets Rumanian founders, Tzara. But he said it in a manifesto, and the avant-garde manifesto tends to be a farrago of provocation and nonsense, into which adroit explications and gems of wisdom are sprinkled. How do you come to grips with such a thing, parsing seriousness from buffoonery? Richard Huelsenbeck, a German medical student and another early Dadaist, trumped any straightforward answer by ending one Dada manifesto: To be against this manifesto is to be a Dadaist! And Tzara himself cheekily said (in a manifesto, no less): In principle I am against manifestos, as I am against principles.

Dada resounds with contradictions. Its artistic productions were pledged to anti-art. Wily in its hoaxes, it could nonetheless be resolutely moral. It was often understood to be an expression of the times, a characteristic outburst of the moment. Yet the Dadaists gladly acknowledged the existence of Dada before Dada, something as old as Buddhism, something attuned to what German philosopher Mynona called creative indifference. This propensity to balance opposites, to be at ease with contradiction, led one of its proponents to call Dada elasticity itself. The affinities with Buddhism have at times drawn attention to a presumed negativity at the heart of Dada, which some Dadaists encouraged. But Dadas

Next page