By the Same Author

Virginia Woolf (Oliver & Boyd), 1963

Shakespeare: The Merchant of Venice (Edward Arnold), 1964

The Waste Land in Different Voices, ed. (Edward Arnold), 1974

Thomas Stearns Eliot: Poet (Cambridge University Press), 1979, 1994

At the Antipodes: Homage to Paul Valry (Bedlam Press), 1982

News Odes: The El Salvador Sequence (Bedlam Press), 1984

The Cambridge Companion to T. S. Eliot, ed. (Cambridge University Press), 1994

Tracing T. S. Eliots Spirit. Essays on his Poetry and Thought (Cambridge University Press), 1996

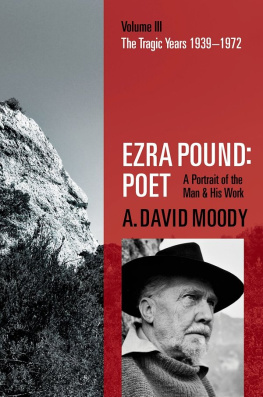

Ezra Pound: Poet. A Portrait of the Man and his Work. Vol. 1: The Young Genius 18851920 (Oxford University Press), 2007

Ezra Pound to his Parents: Letters 18951929, ed. with Mary de Rachewiltz and Joanna Moody (Oxford University Press), 2010

Ezra Pound: Poet. A Portrait of the Man and his Work. Vol. ii : The Epic Years 19211939 (Oxford University Press), 2014

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

A. David Moody 2015

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2015

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014957588

ISBN 9780198704362

ebook ISBN 9780191058981

Printed in Italy by L.E.G.O. S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work

FOR MARY DE RACHEWILTZ

Lux enim

versus this tempest

Contents

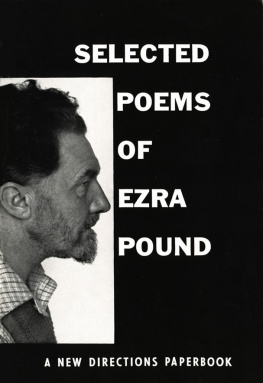

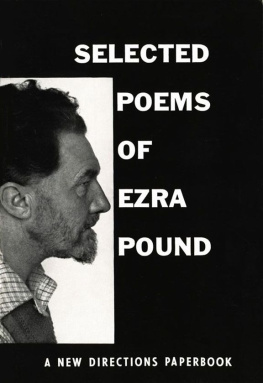

Ezra Pound in 1963, on Calle dei Frati, San Trovaso, Venice, near where he lived in the summer of 1908well, my window | looked out on the Squero where Ogni Santi | meets San Trovaso | things have ends and beginnings (76/462). The Squero where gondolas are repaired is in the background. (Photo Walter Mori, Courtesy of Mary de Rachewiltz) endpapers

Text Illustrations

Bracton:

Uncivil to judge a part in ignorance of the totality

nemo omnia novit

This volume presents the five act tragedy of a flawed idealist and a great poet who, in a time of war, carried to excess his exercise of the rights and freedoms of a United States citizen, and who, in consequence, suffered the loss of both his freedom and his civil rights. Yet out of that personal tragedy in a tragic time there came his finest poetry, a poetry that deliberately rose above tragedy and cultivated instead a mind intent on what humanity had achieved, and might yet hope to achieve, in the way of a well-ordered society at home in its universe.

It was a three-ring, even a four-ring tragedy. There was the war, the destructive element in which his whole world was immersed, and he with it. There was the hubris of his personal involvement in that war on the side of Fascism. That led inevitably to his being perceived as a traitor and a Fascist, when in truth he was neither. Beyond that, as the deeper injustice, there was the accident that it was those whom he trusted to support and aid him who were responsible for his being incarcerated for twelve years and more among the insane, and also for his being made a non-person in law, and kept in that condition for the rest of his life. Behind all, and not subject to the law, even allowed by the law, was his moral offence, the anti-Semitism of which he was guilty, and for which he was made to pay, unlawfully yet in rough natural justice, by the loss of his freedom and his legal rights.

The law, if it had taken its course, should have found him not guilty as charged; and the law should have been allowed to take its course because he was not in fact insanethe judicial finding that he was not competent to stand trial being a travesty of psychiatry and of justice. There would have remained the extra-judicial guilt of his anti-Semitism, and for this he has been justly condemned, and unjustly made a scapegoat for the Nazi Holocaust of the Jews, and for the anti-Semitism endemic in his society. That is the crime at the root of his tragedy, the crime that roused the Furies his friends thought to fend off by having him declared insane. The Furies were not appeased then, and hound him still, seeking not justice but endless prosecution.

Justice requires that the whole truth be told, the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. The whole truth is of course an unattainable idealnemo omnia novit, as the jurist Coke acknowledged, no one knows it all. But at least we can know more than is told by the prosecuting labels automatically stuck onto Pound, reiterating that he was mad, a traitor, a fascist, a money crank, an anti-Semite. The evidence, when one examines it, indicates that he was neither mad nor a traitor. His involvement with Fascism, especially through the course of the 193945 war, is a more complicated matter, too complicated for any simple judgment, having been more an endorsement of its economic and social arrangements than of its politics, and having included, along with a degree of blindness to its operations, an endeavour to reform it with an injection of Confucianism. Indeed, if one must use labels, Confucian would be nearer the truth than Fascist. (As for fascist, that is no longer fit for any responsible use.) But before and above all Pounds primal commitment was always to the principles of the American Constitution. He never once suggested that his country should adopt Fascism, and consistently urged it to be true to its own democratic principles. One of those principles was that the peoples government should control the money supply in the interests of the whole people, with the corollary that the government should not allow the common wealth to be controlled by private banks in their own interest. Only those ignorant of what he actually wrote and stood for, and with a mind closed to the current financial crisis, would regard that as cranky. In the end just one accusation sticks, indelibly, the charge of anti-Semitism, though that, it has to be borne in mind, is not at all the whole truth.

Can we go wrong without losing rightness? Can a man capable at times of speaking evil of the Jews yet be capable of speaking truth about human affairs, and be capable of composing good poetry? Some say not, implacably, blotting and practice [of literature and music] still leave that part of his mind entire. The human truth and the creative vision remain for those who, in the words of Robert Creeley, go to that work to get what seems to me of