Brian Cudnik Astronomers' Observing Guides Faint Objects and How to Observe Them 2013 10.1007/978-1-4419-6757-2_1 Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013

1. The Astronomical Surveys

Abstract

Astronomy is the oldest of the physical sciences and can be traced back to antiquity or at least 5,000 years ago [1]. Looking that far back in time, we see the origins of astronomy mixed in with the religious and astrological practices of pre-history. Ancient societies were already able to tell the wandering planets from the fixed stars and associated these moving objects with gods and spirits. Various cultures have practiced various religions related to astronomy, with the priests playing the role of the professional astronomer of their time, and demonstrating a divine understanding of the movements of the heavens. So it seems that the first few millennia of astronomical involvement of human societies were religious in nature.

Historical Perspective

Astronomy is the oldest of the physical sciences and can be traced back to antiquity or at least 5,000 years ago [1]. Looking that far back in time, we see the origins of astronomy mixed in with the religious and astrological practices of pre-history. Ancient societies were already able to tell the wandering planets from the fixed stars and associated these moving objects with gods and spirits. Various cultures have practiced various religions related to astronomy, with the priests playing the role of the professional astronomer of their time, and demonstrating a divine understanding of the movements of the heavens. So it seems that the first few millennia of astronomical involvement of human societies were religious in nature.

Astronomy has also served a time keeping purpose for the majority of history. The basic motions of Earth and the Moon have, for most (if not all) of recorded history, defined our days, months, and years. Agricultural societies made use of the stars and star patterns as a sort of calendar to know when it was time to plant and when it was time to harvest. One example that comes to mind is the first appearance of the bright star Sirius in the dawn (in August for the mid-northern latitudes nowadays) as noted by the ancient Egyptians. They used this to know when the Nile River would flood and to serve as the start of their calendar year. Due to precession, this occurred near the summer solstice, the longest day of the year for the ancient Egyptians. Western astronomy has its origins in Mesopotamia with the ancient kingdoms of Assyria, Babylon, and Sumer. The earliest known star catalogs originated in Babylonia around 1200 b.c. The Babylonians were among the first (as far as we know) to recognize the periodic nature of astronomical phenomena.

Since the time of the Babylonians, and leading up to the Greek astronomer Hipparchus, people have been interested in surveying the natural world and cataloging what they find. In fact, since the invention of the telescope, and even before, astronomers have been surveying the skies, from Hipparchus cataloging stars in ancient Greece to Messier observing telescopic fuzzy objects from Renaissance France. Astronomers investigated the heavens just as explorers surveyed the surface of Earth. In both cases, new territory was to be found, cataloged, classified, and further studied. Astronomers were limited to what the naked eye could see prior to 1609, when the telescope was first used to look at the skies. Approximately 5,000 stars, the Sun, the Moon, and five naked-eye planets rounded out the pre-telescopic inventory of the cosmos. A handful of deep-sky objects, as well as the occasional comet and supernova, also added to the listing of objects in the known universe prior to the astronomical use of the telescope.

Pre-Telescopic Discoveries of Deep Sky Objects

Deep sky objects known since well before the use of optical aid are listed as follows. The Pleiades and the Hyades were both known to the ancient Greeks and were included in their mythologies; the Pleiades were known pre-historically and were mentioned by Homer about 750 b.c. and by Hesiod about 700 b.c. [2]. The Beehive star cluster, also known as Praesepe (and also M44), was first cataloged by Ptolemy, making it the second earliest cataloged deep sky object and was also observed as early as 260 b.c. by Aratos [3]. Another bright and familiar object, M31 was known to Persian astronomer Abd-Al-Rhaman Al-Sufi (who referred to the object as the little cloud) around a.d. 905 or 954 [4]. Its true nature would not be revealed for another thousand years. The Great Orion Nebula, M42, was probably discovered in 1610 by Nicholas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc. It was also independently discovered by Cysatus in 1611 [5].

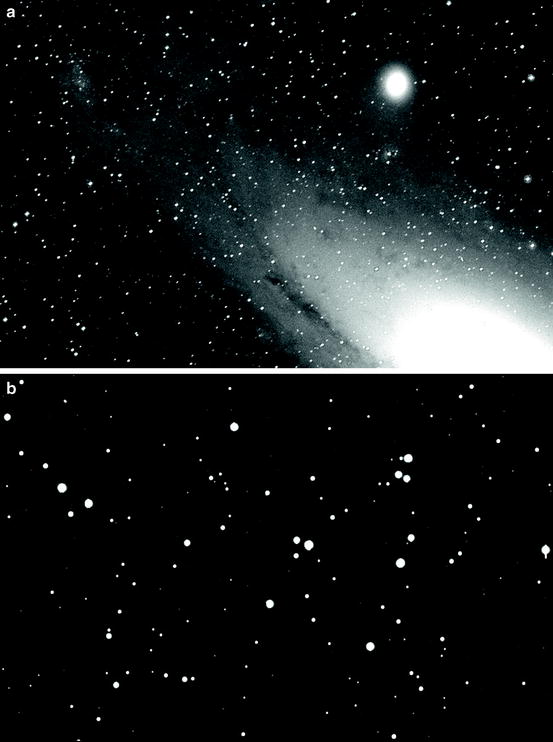

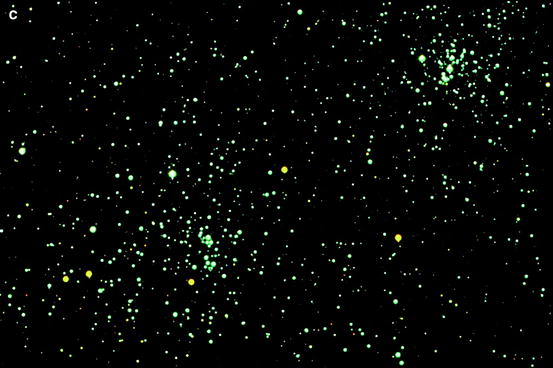

More examples of pre-telescopic discoveries of deep sky objects include M7, Ptolemys cluster known as early as a.d. 130, and Ptolemy himself has described this as the nebula following the sting of Scorpius. [6] It is possible that M39, the open cluster in Cygnus, was observed by Aristotle in 325 b.c. , who noted it as a cometary appearing object [7]; he possibly saw M41 as well in 325 b.c. The double cluster, not cataloged by Messier since he was mainly interested in comet-like objects, was likely cataloged 130 b.c. by Hipparchus [8]. Finally, the Coma Star cluster, Melotte 111, used to be Leos tail, but Ptolemy III renamed it in 240 b.c. for the Egyptian Queen Bernices sacrifice of her hair, as described by legend (Fig. includes modern-day images of three of these objects: M31 (a), M44 (b), and the Double Cluster (c))) [9].

Fig. 1.1.

Examples of objects known before the invention of the telescope: (a) M31, the Andromeda Galaxy, and (b) M44, the Beehive Cluster; and (c) the Double Star Cluster (All three images are courtesy of Paul and Liz Downing).

Two Short Observing Projects Related to These Objects

Although observing projects as a whole arent introduced until with the naked eye. These may not necessarily be faint objects per se, but they give the opportunity to retrace the footsteps (eye-steps?) of those who paved the way in our understanding of what is out there in general over the course of several millennia. To get the best results (that is, views that most closely approximate what these pioneering astronomers must have seen), use an instrument that closely matches the aperture (of the mirror or lens) of that used by each astronomer, or use your own if you do not have access to such telescopes.

Table 1.1.

Years of discovery (or at least when they were first noted and recorded and the record survives) of some of the brighter deep sky objects

Object | Discoverer/Person who first noted object(s) | When discovered or first noted |

|---|

Pleiades (M45) | Homer/Hesiod | 750 B.C. /700 B.C. |

M39 open cluster | Aristotle | 325 B.C. |

M41 open cluster | Aristotle | 325 B.C. |

Beehive/Praesepe (M44) |