Table of Contents

To my family and the folks who have always looked out for me.

The year is 1985 and Professor John D Swsinhnder [sic] is getting into his rocket. 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, blast off! He was drifting in space at a speed of ten thousand miles an hour. In a short time he was on the moon. He is going there to prove that the moon is made of green cheese. He picked up a rock and bit it.

He said, If this is cheese than [sic] my teeth are not cracked. But they were.

In a minute not to lose he got in his rocket and went back to see his dentist. He did not prove that the moon was made of green cheese. But instead he proved never bite rock.

FROM A TRIP TO THE MOON,

OSCAR HIJUELOS, AGE TEN

A Prelude of Sorts

Seems just like yesterday (an illusion) that I was sitting out front on my stoop on 118th Street, on an autumn day, in 1963 or so, feeling rather indignantly disposed and pissed off because my best friend from across the way, with a somewhat smug look in his eyes, kept blowing smoke into my face. He was thirteen, a year older than me, and had already been going through at least a carton of Winstons a week for as long as I could remembercigarettes that his mother, the venerable Mrs. Muller-Thym, coming back from the A&P, gave, fair-mindedly, to each of her sons on Fridays. (Think he must have started smoking at the age of seven or eight.) We usually got along like pals, running through the backyards and basements together, or else hanging out in the book-laden clutter of his room, playing cards and chess or listening to jazz recordings by Art Blakey and Ahmed Jamal, while occasionally sneaking rum and whiskey from his fathers stash of high-class booze down the hall, which wed mix into glasses of Coca-Cola, without ice, and drink until the world went spinning and everything became beautiful in an exciting way. The guy was definitely head and shoulders smarter than just about anyone else in that neighborhood, including me, and generous to boot, for he was always giving away his cigarettes and candy and loose change on the street. But on that particular afternoon, he had gotten some kind of hair up his ass. With a smirk on his face, and walking right up to me, he had blown, slowly and with great self-satisfied deliberation, rings of that smoke at my mug. I dont know why he did thisperhaps because he, like so many of the other kids on that street, sometimes thought me passively disposed on account of the fact that my mother, never forgetting my childhood illness, had always kept a tight leash on me. Or because he just felt naughtily inclined or wanted to express some notion of superiority that day. But whatever he may have been thinking in those moments, I discovered that I had a fairly short fuse. So when I told him, Come on, man, dont do that! in the manner that kids in those days talked, and maybe, But hey, Im not messing with ya, and he kept blowing that smoke at me anyway, I yanked the cigarette out of his hand and put it out on his head.

Thankfully, its burning tip met with the thick matting of his slickened dark hair, but I can still remember the crisp sound it made, like air being quickly released from a bicycle tire, and, of course, that strangely repellent smell of singed organic matter, which foreshadowed, to my young Catholic mind, the possible punishments of hell. Perhaps I ended up chasing him around the block, but he was always too fast for me, or perhaps, I cant exactly remember, he ran down into a basement or the park, hiding out somewhere in the bushes along one of the terraced walkways that descended from Morningside Drive into East Harlem, on tracks of cracked, glass-strewn pavement. If so, he might have waited until sometime near dark, while I, out of sorts and craving a cigarette of my own, went home to yet another one of those evenings in our Cuban household that tended to leave me feeling restless and confused.

PART ONE

The Way Some Things Worked Out

CHAPTER 1

When I Was Still Cuban

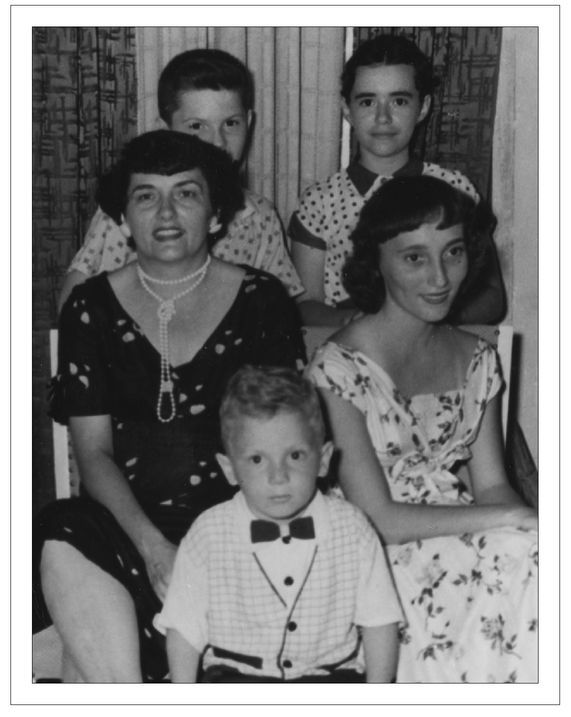

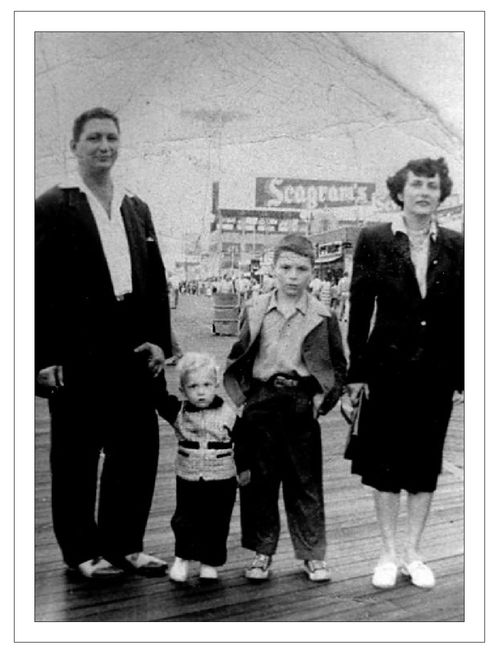

Pretend its sometime in 1955 or 1956 and that you are hanging over the roofs edge of my building, as I often did as a teenager, looking down at the street some six stories below. You would have seen, on certain mornings, my mother, Magdalena, formerly of Holgun, Cuba, and now a resident of the United Stays, pacing back and forth fitfully before our stoop, waiting for a car. She would have been eye-catching, even lovely, with her striking dark features and pretty face, her expression, however, somewhat gaunt. Muttering to herself, she would have had the jitters, not only from her inherently high-strung nature but also because shed probably spent the night sitting up with my pop worrying about their youngest sonme.

As green and white transit buses came forlornly chugging up the hill along Amsterdam from 125th Street, she would have stood there, perhaps with my older brother, Jos, by her side, watching the avenue for a car to turn onto the street, all the while dreading what the day might hold for her. Sometimes it would have rained or it would have been brutally cold. Sometimes it would be sunny, or snow would be falling so daintily everywhere around her. She might call out to a friend to come down from one of the buildings nearby, say my godmother, Carmen, mi madrina, a red-haired cubana, with her flamenco dancers face and intense dark eyes. Coming down in a bathrobe and slippers to reassure her, shed tell my mother not to worry so much, it wasnt good for her after allthe kid would be fine. Ojal, my mother, her stomach in knots, would answer, though always shaking her head.

A car would finally pull over to the curb. The driver, a friend of my fathers, or someone he had paid, would take her either to 125th Street and Lenox Avenue, where she might catch a train, or directly up to Greenwich, Connecticut, where I, her five-year-old son, lay languishing in a hospital. Through the Bronx and over to the highway north to Connecticut they would go and, coming to that placid town, the kind of place shed never have visited otherwise, enter a different world. In the spring, shed ride along the loveliest of shadow-dappled streets, the sunlight shimmering through the leafy boughs of elm and oak trees overhead, as if they were passing through a corridor like one of the roads out of Havana; and in the winter, snow, in plump drifts and brilliant, would have been everywhere, so Christmas-y and postcard-pretty. After following her directions, which she would have recited carefully to the driver from a piece of papertorn out of a composition notebook page or from a brown grocery bagthey would have found the hospital along King Street, off in its own meadow and reached by a winding flagstone driveway, the Byram Woods looming as a lovely view just nearby.