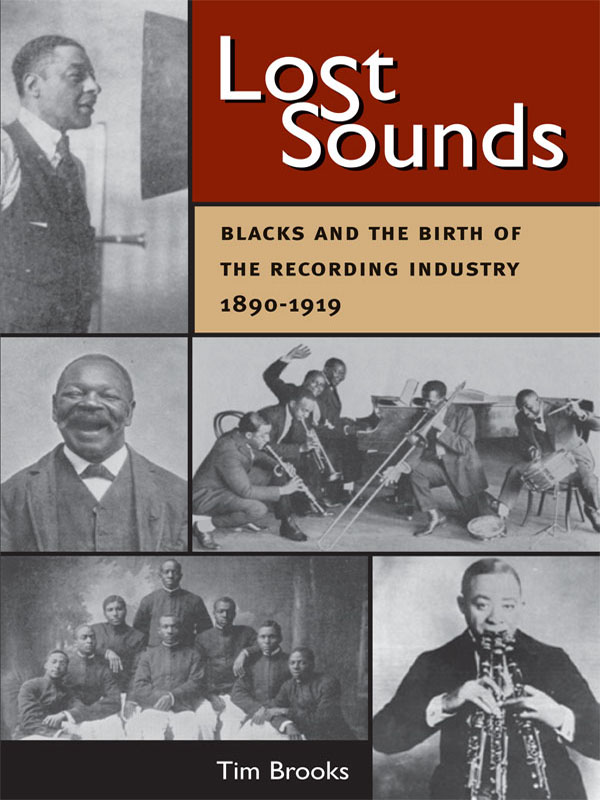

Lost Sounds

Music in American Life

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

Publication of this book was supported by grants from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music and from the Henry and Edna Binkele Classical Music Fund.

First paperback edition, 2005

2004 by Tim Brooks

Appendix 2004 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

2 3 4 5 6 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

The Library of Congress cataloged the cloth edition as follows:

Brooks, Tim.

Lost sounds: blacks and the birth of the recording industry, 18901919 / Tim Brooks ; appendix of Caribbean and South American recordings by Dick Spottswood.

p. cm. (Music in American life)

Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-252-02850-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. African AmericansMusicHistory and criticism.

2. Sound recording industryHistory.

3. MusicUnited StatesHistory and criticism.

I. Spottswood, Dick (Richard Keith)

II. Title.

III. Series.

ML3479.B76 2004

781.64'149'08996073dc21 2003001102

Paperback ISBN 0-252-07307-X

CONTENTS

PREFACE

George W. Johnson has always seemed to me an intriguing character. The first black recording star, he is almost completely forgotten today. Colorful stories swirled around his life. Had he been born a slave? Was he really discovered panhandling on the streets of Washington, D.C.? When did he begin recording, and how popular were his records? Was he really hanged for murdering his wife?

In the late 1980s I began doing research to try to learn more about this elusive character. There were no books about him, and the only serious articles, written by pioneering researcher Jim Walsh in 1944 and 1971, left many questions unanswered. What followed was a long odyssey through census records, slave registers, dusty legal archives, early newspapers and catalogs, as well as trips to the beautiful old towns of Virginias Loudoun County (where he was born), New Yorks Hells Kitchen (whose streets he walked), and a New York area cemetery (where he came to rest). Finding copies of his records was a challenge, since most had been out of print for more than eighty years.

As the story of Americas first black recording artist slowly came into focus, it became apparent that there were other black artists at the time, equally unrecognized, whose stories needed to be preserved. I kept running into their names in my research. So I decided to expand the study to cover all African Americans who recorded commercially in the United States prior to the explosion of interest in black music in 1920. This time period has received little attention, with some writers even denying that there were any recordings by blacks in the earliest days. Eventually I identified nearly forty black artists and groups who had recorded during this period. Remarkably, they represented nearly every type of black artistic expression, from a street performance like that of Johnson, to minstrelsy, vaudeville, theater, spirituals, jazz, poetry, speech, even the concert halla veritable cross-section of black art and culture.

My original intent was to add brief biographical sketches of these other artists, drawn from previously published work. How naive I was! There was nothing published about most of them, and their biographies had to be painstakingly reconstructed from original sources, just like that of Johnson. Back to the archives and microfilms, and the search for original cylinders and 78s. Many of these people were minor names in the entertainment world, so little had been written about them when they were alive. Of course their race was another reason they were ignored in official records and the media. Even when biographies existed (like those for boxing champ Jack Johnson), they disagreed on so many details that original research was required, especially regarding the recordings.

I hope that the reader will excuse the preliminary nature of much that appears in these pages and that others will take up the crusade and uncover more about the pioneers who introduced America to a wide range of African American culture before it became economically rewarding to do so. This book merely opens the door on a world we need to celebrate and learn more about.

These biographies are as complete as the author could make them, but there are doubtless errors as well as additional recordings and artists yet to be discovered. Additions and corrections from readers are enthusiastically welcomed; send these to me at P.O. Box 31041, Glenville Station, Greenwich CT 06831.

Tim Brooks

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Nobody does it alone. Like the artists profiled here, I have been helped by many hands along the way. Whether it was checking their local libraries, raiding their own files (or, in one case, giving me their files), making copies of articles or tapes of otherwise unobtainable recordings, taking pictures of important sites, or simply providing leads, researchers in the United States and around the world have responded to my inquiries during the long years this book was being researched. Some of them probably wondered if the book would ever actually be published. My debt, and yours, to them is immense.

Among those contributing information and advice were Lynn Abbott, George Adams (a member of the Fisk Jubilee Singers in the 1950s), Barry Ashpole, Dr. Lawrence Auspos, Arthur Badrock, Mark Berresford, Carol Blais, William Bryant, Sam Brylawski, Peter Burgis, Brigitte Burkett, Paul Charosh, Norm Cohen, Frederick Crane, John S. Dales, Prof. Allen Debus, John Devine, Sherwin Dunner, Bevis Faversham, Patrick Feaster, Harold Flakser, Ray Funk, David Giovannoni, David Goldenberg, Tim Gracyk, John Graziano, Dr. Lawrence Gushee, Lawrence Holdridge, Rick Huff, Eliott Hurwitt, Asa M. Janney, David Jasen, Bill Klinger, Allen Koenigsberg, Len Kunstadt, Gary Le Gallant, Dr. Rainer E. Lotz, Richard I. Markow, Michael Montgomery, William Moran, Kurtz Myers, Dr. Charles Poland, Steven Ramm, Quentin Riggs, Prof. Thomas Riis, Brian Rust, Howard Rye, Doug Seroff, William Shaman, Peter Shambarger, Steve Smolian, Jean Snyder, Bronwen C. Sounders, Dick Spottswood, Linda Stevens, Paul W. Stewart, Patricia Turner, Steve Walker, and Prof. Raymond Wile.

Institutions from which I drew information included the Center for Black Music Research at Columbia College, Chicago (Suzanne Flandreau, Dr. Sam Floyd); Detroit Public Library (Agatha Kalkanis); Edison National Historic Site (Jerry Fabris, George Tselos, Doug Tarr); Emerson College Archives (Robert Fleming); Greenwich Public Library; Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University (Dr. Bruce Boyd Raeburn); John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York (Eileen Rowland); Library of Congress (Sam Brylawski); New York City Municipal Archives (Kenneth R. Cobb); New York Public Library Theater Collection and Rodgers and Hammerstein Archive of Recorded Sound (Don McCormick); Ohio Historical Society (Thomas J. Rieder); Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; Sony/Columbia Records Archives (Martine McCarthy, Nathaniel Brewster); Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Virginia (Jane Sullivan); U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Hartford, Connecticut, office; and the Historical Sound Recordings Archive at Yale University (Richard Warren).

Next page

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.