To John and Gavin

With love

CONTENTS

S SPLAT!!!!! THE MOUTHFUL OF WINE STRIKES the side of the small stainless steel sink, adding a few red splashes to the basin before disappearing down the drain. The taster frowns at the aftertaste that lingers briefly on his gums, his tongue, and the inside of his cheeks. Too tart and herbaceoushes sure its been acidifiedand stripped of flavor. The wine is the fourth in a lineup of twenty-six California Cabernet Sauvignons. He knows hed be generous to give this one a score in the low 80s. Hell taste it again, but right now it looks like a disappointing 81.

The next wine has plenty of saturated purple colorits almost opaquebut he knows many of these California Cabs do. Eyes narrowing, he blocks out all distractionsthe hum of arriving faxes, the sound of the rain on the window, the barking of his basset hound outside, and a ringing phone and the murmur of voices in the next roomand sticks his nose into the glass, then inhales quickly with a short, silent snort. A panoply of scents, he thinks. Is that a cassis-like note? Blackberries, or is it black cherries? To confirm what his nose tells him, he tips the crystal glass, sucks in a generous mouthful of wine, and lets it spread across his tongue. After lowering the glass, he swishes the liquid around his mouth for a few seconds as though gargling mouthwash, pauses for a moment while staring into space, his eyes unfocused, then spits it into the sink with expert aim and force. It forms a perfect arc that pings sharply against the metal.

He is still tasting the wine, his mind completely concentrated as he savors the persistent echo of flavor and lingering scents and sorts out his impressions: explosive richness, yes; oodles of powerful ripe black cherry fruit... definitely some cassis there; a thick, voluptuous texture, and a wonderfully spicy note in the 30-second finish. Its a hedonists dream.

The number comes to him. This is a 95he is certain of that.

When these scores are published a month later, the producer of the 95-point wine will celebrate. If his is a new tiny winery, people will call to congratulate him. Hes made the 90+ club. His wine will be sold out by the end of the weekif, indeed, it takes that long. The recipient of the 81-point wine will gnash his teeth; it may be hard to convince some retailers to buy this particular bottling. Too many scores like this and his fortunes will start to decline.

By noon, the taster will have passed judgment on several dozen wines, judgments that will create overnight successes, deflate long-held reputations, and move markets around the world. They will be anticipated eagerly by retailers, who will quickly order the wines with scores of 90 and above, and with trepidation by winery and chteau owners, who know the scores can cause a rise or fall in their prices. These judgments will be regarded as Holy Writ by thousands of serious wine consumers.

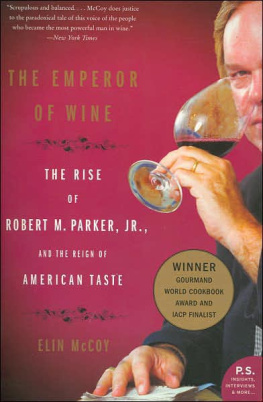

Why? Because the taster, Robert M. Parker, Jr., whose palate has been called the oenological equivalent of Einsteins brain, is the most powerful wine critic in the world. But even more than that, right now he is the most powerful critic in any field, period. If a New York film critic pans or praises a film he may influence its reception in that city, but his view wont have the same effect on moviegoers in Paris or Tokyo, nor will film directors around the world create movies to appeal directly to his taste. But over the past twenty years Parkers passions and ideas have influenced how wine is made, bought, and sold in virtually every wine-growing and wine-drinking country on earth, and there are winemakers who consciously aim to make a wine that will seduce him.

Despite the worlds attention and unending acclaim, Parker is a controversial figure in the wine world. He has saved wineries from bankruptcy and turned winemakers into millionaires and unknown wines into sought-after collectibles, but his low scores for other wines have meant lower prices and diminished reputations. He has been sued and received death threats. Parker is blamed by some for helping to turn the world wine industry into a single global market, causing prices to skyrocket, and for reshaping the taste of wine to his own personal preference for dark, high-alcohol wines with lots of power and intensity, and in the process killing tradition and reducing great wines to mere numbers. Others revere him, claiming he is largely responsible for the vastly improved quality of wines made across the globe and is the wine consumers best friend.

But for all, Parkers scores are the wine industrys report card.

How did an American raised on soft drinks, who never tasted fine wine until he went to Europe during college, become such a colossus? What were the times and circumstances that made his extraordinary rise possible?

M ONKTON, MARYLAND, POPULATION 4,615, seems an unlikely hometown for the worlds most important wine critic. When Robert McDowell Parker, Jr., was born in Baltimore on July 23, 1947, the landscape north of the city around Monkton was much as it is nowa typical rural American mix of working dairy farms, white clapboard farmhouses and modest brick ranch houses, and patches of second-growth woods and rolling fields. As I drove to his house to spend a day with him, though, a few large, white-fenced horse farms alerted me to the presence of the affluent elite of hunt-country blue bloods who have long presided over point-to-point horse races each spring and fall and attended the annual Blessing of the Hounds at the local Episcopal church.

But Parker didnt grow up on one of those grand estates, where the occasional bottle of wine may have graced the table even back in the 1940s and 1950s. His parents married at eighteen and never went to college. For the first few years of his life, home was the family dairy farm in Monkton, only a 10-minute drive from where he lives today. Some of the first smells to hit his now famous nose were fresh milk, cows in the barn, and hay warm from the sun.

Three hundred years ago, when barrels of Bordeaux wines like Chteau Haut-Brion and Chteau Margaux were being regularly auctioned off in London, Monkton and all of northern Baltimore County was still the domain of the Susquehannock and Piscataway Indian tribes. In 1634 it was granted to the kings representative, Charles Calvert, the third Lord Baltimore, who founded Maryland and leased thousands of acres to settlers before giving a choice parcel that included Monkton to his fourth wife. Besides dairy farming and creameries, grist- and sawmills were the earliest industries here, now long gone; the old stone mills survived as antiques shops and homes. Back in the 1950s, when Parker was growing up, Monkton and neighboring Parkton (where he now lives) were mere clusters of houses and churches; Monkton had only a tiny food market, no library or dry cleaner, and the nearest drugstore was 15 miles away.

Today the town is bigger, encompassing all-American nondescript shopping plazas with supermarkets as their centerpieces; a main street with the standard town businessesbanks, pizzerias, auto repair shops, and garden centers; and a bland brick high school set in a field with a sign that reads Hereford High School, Home of the Bulls. This wasnt a fine wine and food place in the 1950s, and it still isnt, despite the growing number of executive-style development homes and the presence of two tiny wineries a few miles away. The distance to Baltimore is only 27 miles but must have seemed farther before Interstate 83 was built, linking the city to points north.

Forget the wide range of gourmet staples urban Americans take for granted. The store nearest Parkers house in Parkton turned out to be just a country place with an old-fashioned Drink Coca-Cola sign and out front, a barrel of cabbage flowers edged with American flags. The local give-away paper has ads for popular wines he ignores, like Beringer White Zinfandel, and lists of tree farms where you can cut your own for Christmas. The score of the latest Hereford Bulls basketball game is the big news.

Next page