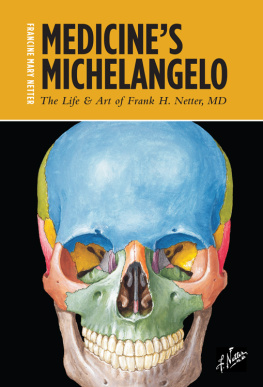

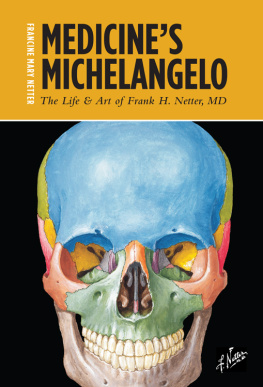

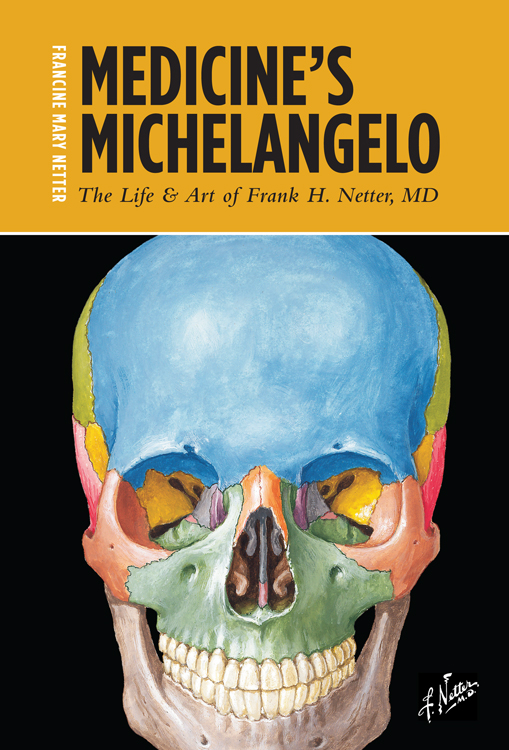

Skull: Anterior View, Frank H. Netter, Atlas of Human Anatomy, Ciba-Geigy, Summit, New Jersey, 1989, plate 1, courtesy of Elsevier.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

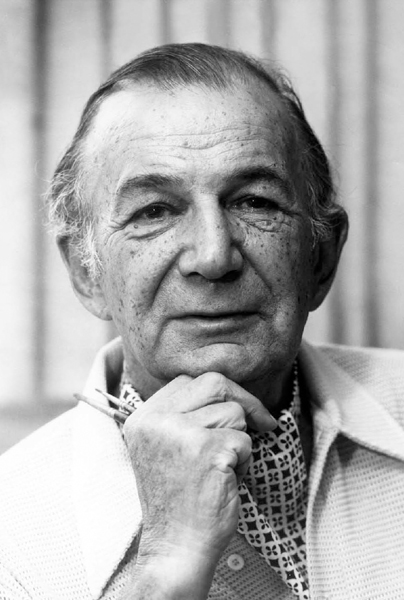

Photo: Frank H. Netter and his daughter Francine Mary Netter, Christmas Eve, 1973.

Dr. Frank Netter helped me through medical school.

Frank Netter, MD, taught me and generations of other physicians the splendid details of the human body. Through his many works of medical art we learned anatomy and much more. I never met this giant of medicine, who left us in 1991, but his amazing life and work come alive in this fascinating book by his daughter Francine Mary Netter. She tells a tale that is rich in detail and realisticwe see the real Frank Netter.

We learn about this complex man, who was artist, then physician, then medical artistand through his decades of work we meet a host of famous physicians, practically a whos who of medical science from the 1930s to the 1990s. Frank Netters collaborations with them led to his extensive set of books, published by the international pharmaceutical giant Ciba-Geigy.

I am amazed at how timeless his work ishe was entirely up to date in many areas and had a way of steering clear of details that were not necessary and might have dated his art. Many of his drawings from the 1970s and 1980s are still highly relevant despite the incredible progress in medical science.

One of Frank Netters great contributions was to make learning easier by incorporating so many elements that are not nearly so well captured by any combination of photographs, diagrams, pathways and description. It is all there in every Netter drawing. He was a great medical artist whose pictures combine art and science. Dr. Netters works live on even now, more than two decades after him, in Netters Anatomy Atlas and many other publications.

And now this new book brings insight into the man behind the medical artistry. As I read it, I vividly recalled the impact his pictures had on me as a young medical student four decades ago.

I believe you too will enjoy this story of Frank Netterhis life and times and his art.

William L. Roper, MD, MPH

Dean of the School of Medicine, Vice Chancellor for Medical Affairs

and Chief Executive Officer of the UNC Health Care System

at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Frank Netter was the quintessential New Yorker. He knew his way around among the skyscrapers and the parks and the historic sites. Give him a street address and he could tell you the cross street and how best to get there, and he could generally recommend a nice place in the vicinity to have lunch.

He stood 5 feet 10 inches tall, at least he had in his younger days, and maintained a trim figure. His hair, black with just a touch of gray at the temples, he wore parted in the center and combed back in waves off his face. With dark eyes, olive skin and aquiline nose, he was a handsome man. If you had seen him walking down Fifth Avenue in his camel-colored cashmere overcoat and tan felt fedora in the winter, you might have taken him for a stockbroker or a lawyer or even the physician he was. But underneath that conservative, citified exterior he favored a dashing, debonair, sometimes outlandish style befitting the artist.

Therein lies the conundrum, for he was both physician and artist. The doctors consider me an artist, and the artists consider me a doctor. I am kind of in the territory between the two, he told his young colleague Dr. Frederick Kaplan.

On the top floor of the mansion where we lived when I was a child, Daddy had a large art studio where he spent his days and nights making pictures. I remember him working long hours in his studio and emerging with a shadow of a beard, which scratched when he kissed me. If you had asked me then, I would have told you that Daddy spent all his time painting. But I can now tell you with certainty that that was not the case. For each picture he made, and he made over 4000 of them for Ciba Pharmaceuticals alone, he spent most of his time studying, thinking and planning.

With some frequency I used to go up to the studio to see him, to watch him draw and paint and simply to be with him. Daddy would tell me about the medicine in the picture he was making at the time. If he made a picture of the heart, he explained to me how it worked to circulate the blood. If it was a picture of the intestines, he taught me about digestion. He never held anything back because of my young age. The pictures told the story and made it all clear to me. We talked about all the various things that fathers and daughters discuss, and I learned much about my father, and a great deal about art and medicine.