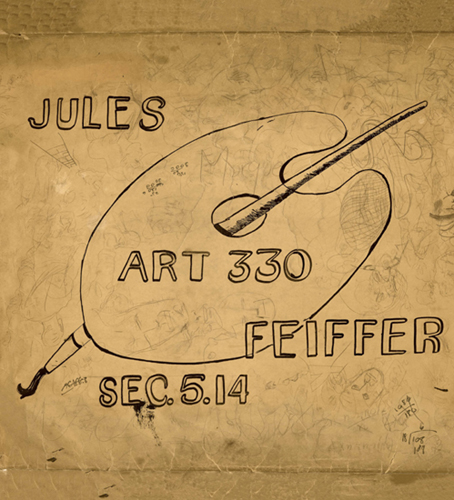

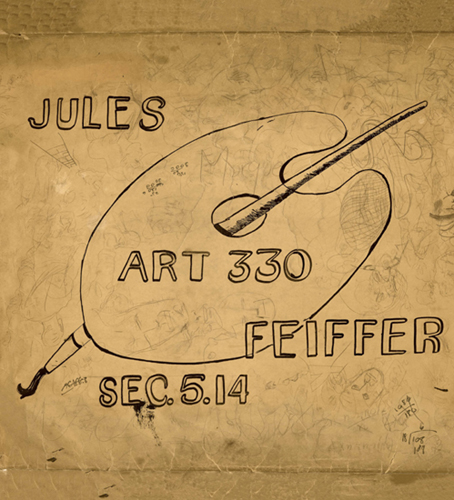

Jules Feiffers art portfolio (front), from a class taught by Max Wilkes in Feiffers junior year at James Monroe High School in the Bronx, c. 1946.

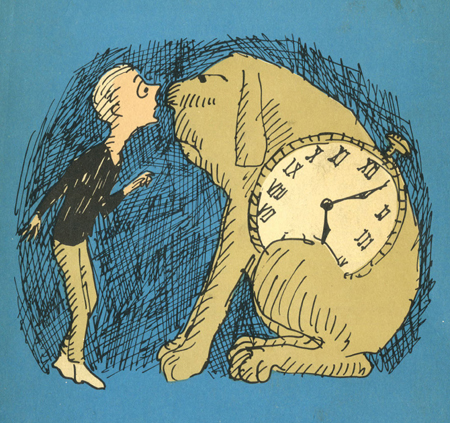

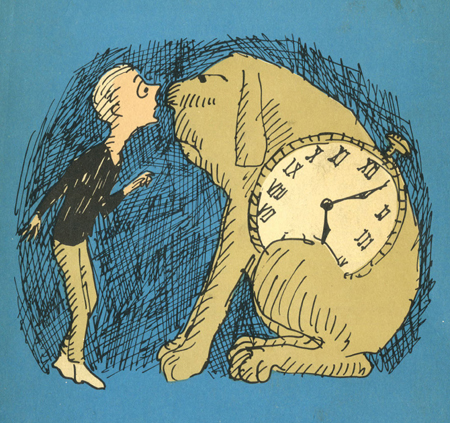

Undated illustration from series appearing on .

Untitled dancer, June 2014.

Jules Feiffer as Fred Astaire, created for Barrett, the Honors College at Arizona State University, to celebrate his visit as Flinn Foundation Centennial Lecturer and Scholar-in-Residence, November 27December 2, 2006.

Original art for portfolio sample, c. 1957.

A

CONTENTS

by Leonard S. Marcus

by Mike Nichols

Detail from The Man in the Ceiling, 1993.

A

INTRODUCTION

Boy with Pencil, Man with Pen

by Leonard S. Marcus

ules Feiffer is an American original, an artist and writer of breathtaking ambition, fearless honesty, impertinent wit, and unyielding faith in the value of the quintessentially American act of having ones say. For more than forty years, as the creator of the weekly Village Voice cartoon strip Feiffer, he blithely took the measure of the people in power at every level of our national life: from megalomaniacal presidents to browbeating parents, from buttoned-down corporate types to phony-baloney hucksters and hipsters of every stripe and persuasion. Week after week, as the ultimate antiOrganization Man, Feiffer demolished for readers the psychic distance between his audience and the double-speaking people-in-high-places of the moment, as much as to say, Were all in this together and so have every right and reason to know the score. A Feiffer strip was a bracing wake-up call. A prompt to keener self- and civic awareness. It was also usually good for a laugh.

ules Feiffer is an American original, an artist and writer of breathtaking ambition, fearless honesty, impertinent wit, and unyielding faith in the value of the quintessentially American act of having ones say. For more than forty years, as the creator of the weekly Village Voice cartoon strip Feiffer, he blithely took the measure of the people in power at every level of our national life: from megalomaniacal presidents to browbeating parents, from buttoned-down corporate types to phony-baloney hucksters and hipsters of every stripe and persuasion. Week after week, as the ultimate antiOrganization Man, Feiffer demolished for readers the psychic distance between his audience and the double-speaking people-in-high-places of the moment, as much as to say, Were all in this together and so have every right and reason to know the score. A Feiffer strip was a bracing wake-up call. A prompt to keener self- and civic awareness. It was also usually good for a laugh.

Throughout the tumult of the Cold War, Vietnam era, sexual revolution, civil rights struggles, womens movement, and trickle-down Reaganomics, Feiffer kept his satirical cool, reading between the lines of mind-bendingly complex issues with anthropological detachment and a comedians instincts for incongruity and timing. The short-form cartoon strip format he adopted, averaging six to eight panels per installment, proved to be an ideal perch from which to parse the absurdityor hypocrisyof just about anything. A Feiffer strip was part Nichols and May stand-up routine, and part breakthrough session on the analysts couch. It was Seinfeld and The Daily Show rolled into one, with each of those latter-day television cult sensations doubtless owing at least a splash of its initial inspiration to Feiffers own long-running one-man show: the cartoon for grown-ups as deadpan reality check, rendered in the fast-paced, freewheeling gestural line and sardonic patter of an artist and monologist in perpetual overdrive. It is hardly surprising that a strip built on pithy telegraphed dialogue and dramatic confrontation would, before long, catapult Feiffer into the realms of theater and film as well.

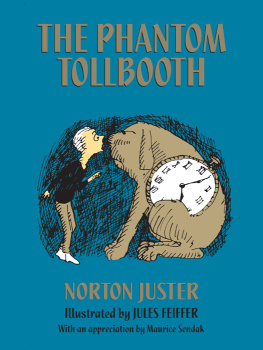

Detail from the cover of The Phantom Tollbooth, 1961.

First and foremost, Feiffer demands to be seenas it is in the pages that followas a worthy contribution to the great Western tradition of satirical illustration, the history-making pictorial commentaries of artist-observer-provocateurs such as William Hogarth, Thomas Rowlandson, James Gillray, Honor Daumier, George Grosz, and, among Feiffers contemporaries, David Levine, Edward Sorel, Ralph Steadman, and Ronald Searle. To scan the shelves of art books lined up on Feiffers studio walls is to quickly recognize that the gangs all here: that on his way to fashioning one of contemporary satirical drawings most distinctive graphic styles, Feiffer, ever the autodidact and cultural magpie, did his homework; that, from an art historical point of view, he has always known exactly what he was doing.

Feiffer first fell in love with art as an ardent Depression-era fan of the funny papers. To his little-boy pantheon of Sunday supplement super heroes, he soon added the hard-boiled newsprint artists/storymen who created the characters, vowing one day to join their ranks. The lasting impression that masters of the genre, such as Milton Caniff and Feiffers own eventual mentor Will Eisner, made on him can be felt in the coiled-spring tension and swagger of just about any Feiffer drawing, whether the subject happens to be an anonymous loser or Richard Nixon or Fred Astaire. For all sorts of reasons, Astaire came to occupy a special place in the Feiffer pantheon, not only because he (unlike the notoriously klutzy artist) danced so exquisitely, but also because Astaire (much like Feiffer) is known to have worked so insanely hard to achieve the appearance of effortless grace. Over time, dance emerged as a recurring theme both in and out of the weekly strip, and as Feiffers craft became second nature to him, drawing became his way to dance.

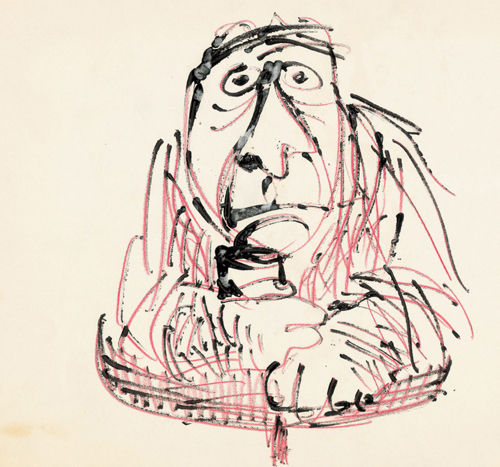

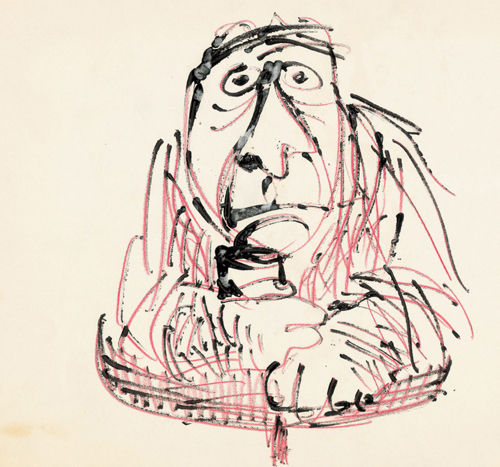

Anxious Man, Feiffer working in the key of William Steig. Original art for portfolio, c. 195354.

Theres an intriguing logic to Feiffers late-in-the-game decision, sometime in the early 1990s, to make writing and illustrating childrens books the primary focus of his creative energies. For decades, the drawings he had done on a lark for Norton Justers uproarious fantasy for children, The Phantom Tollbooth (1961), had stood apart from his work as a one-off excursion into a specialized realm he had long ago ceded to his friend Maurice Sendak. Yet during all those years, childhood kept coming up as a theme and even obsession in Feiffers cartooning, most often for the purpose of exposing the adult worlds fears of people more open-minded than themselves, and the cruel and duplicitous behavior toward the powerless young that frequently followed as a consequence. By the mid-1990s, as the Village Voice strip was coming to an end and playwriting was proving to be a far from reliable alternative means of support, memories of his own childhood passion for comics began to beckon, as did the appeal of a greatly expanded juvenile publishing world.

Even so, it was not mere nostalgiaor opportunitythat pointed Feiffer in the direction of creating illustrated stories for kids. It was also an insight into the original impetus behind his work as a satirist, which went something like this: If you really

Next page

ules Feiffer is an American original, an artist and writer of breathtaking ambition, fearless honesty, impertinent wit, and unyielding faith in the value of the quintessentially American act of having ones say. For more than forty years, as the creator of the weekly Village Voice cartoon strip Feiffer, he blithely took the measure of the people in power at every level of our national life: from megalomaniacal presidents to browbeating parents, from buttoned-down corporate types to phony-baloney hucksters and hipsters of every stripe and persuasion. Week after week, as the ultimate antiOrganization Man, Feiffer demolished for readers the psychic distance between his audience and the double-speaking people-in-high-places of the moment, as much as to say, Were all in this together and so have every right and reason to know the score. A Feiffer strip was a bracing wake-up call. A prompt to keener self- and civic awareness. It was also usually good for a laugh.

ules Feiffer is an American original, an artist and writer of breathtaking ambition, fearless honesty, impertinent wit, and unyielding faith in the value of the quintessentially American act of having ones say. For more than forty years, as the creator of the weekly Village Voice cartoon strip Feiffer, he blithely took the measure of the people in power at every level of our national life: from megalomaniacal presidents to browbeating parents, from buttoned-down corporate types to phony-baloney hucksters and hipsters of every stripe and persuasion. Week after week, as the ultimate antiOrganization Man, Feiffer demolished for readers the psychic distance between his audience and the double-speaking people-in-high-places of the moment, as much as to say, Were all in this together and so have every right and reason to know the score. A Feiffer strip was a bracing wake-up call. A prompt to keener self- and civic awareness. It was also usually good for a laugh.