Dedicated to Robert DeShaun Peace and to his heart, Jacqueline Peace

A UTHORS NOTE

I F YOURE GOING to tell the story of a man, tell the whole story.

I was sitting in Cryans Beef & Ale House in South Orange, New Jersey, with Jason Delpeche, one of Robert Peaces friends dating back to elementary school. His words were not so much a command as they were an observation: if the intent of these pages was to recount the life of a friend who has diedwho could neither tell nor defend his own storythen I had better recount that life well, using all means available.

This story is told through memory, observation, and documentation: mine, of course, but primarily that of many dozens of others, including Robs family, friends, lovers, classmates, teachers, neighbors, colleagues in the professional world, and colleagues in the drug world. In addition, many people have contributed to this telling who did not know Rob at all but have keen perspective on one or more of the many complicated milieus in which he traveled: lawyers who worked for or against his father, politicians in Newark and the surrounding townships, community workers, police who patrol the streets on which he grew up, police who investigated his murder, academics, college administrators, state prison inmates, state prison employees, and more. I sought out anyone who might have a shred of perspective not only on Robs direct experiences but also on the places and structures that informed those experiences. The result has been more than three hundred hours worth of recorded interviews which, paired with my own memories, eventually became this book. Much of this material is subjective, but so is any human life.

The dialogue that appears in this book was taken directly from these interviews. Though recalling precise exchanges, in some cases from decades ago, can be an inexact science, I am confident that the words Ive written reflect very closely the words that were said. In instances where more than one person was present for these conversations, I have fact-checked their accuracy.

Segments relating to Robs consciousnesshis thoughts, feelings, various states of beingcame from sentiments he shared with others during the respective time periods in which they took place. I acknowledge that it is impossible to fully understand a mans interior, particularly a man as complicated as Rob Peace, and I included such passages only in cases where the recollections were explicit and specific.

There are moments detailed herein in which Rob was alone or was interacting with someone who has also passed away, and so no one could attest as to what actually happened. Again, I relied on conversations he later had with friends and family. On the very few occasions where Rob never did relate the goings-on both within him and without, I used language to indicate that the content is based on the projections of myself and/or those who knew him well.

Names and some identifying characteristics have been changed.

Part I

Chapman Street

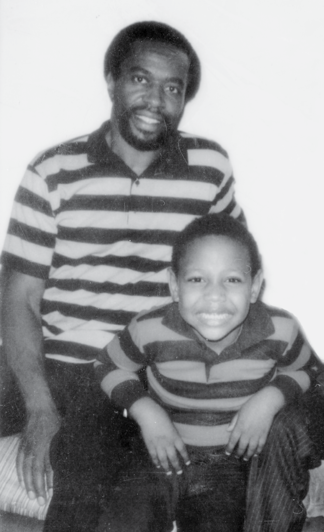

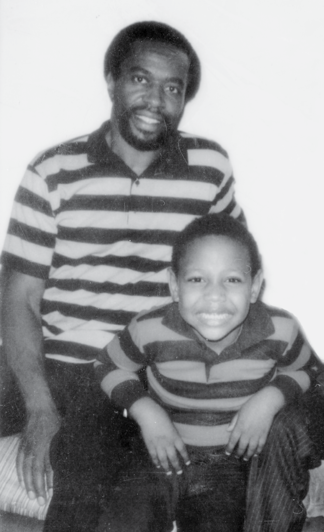

Rob with his father, Skeet Douglas, in 1985.

Chapter 1

W HY IS THE AIR NOT ON ? Jackie Peace asked from the back of the car.

It wears the engine, her mother, Frances, replied from the drivers seat. You cant bear it for four blocks?

He just feels hot to me, real hot. And then, when her mother chuckled: Whats funny?

Youre a brand-new mama and thats why you have no idea.

Idea of what now?

Babies are strong. They can handle just about anything.

Robert DeShaun Peace, the baby in question, lay sleepy-eyed and pawing in Jackies arms. He was a day and a half old, eight pounds, ten ounces. When hed first been weighed, the number had sounded husky to her. Now, outside the hospital for the first time, he felt nearly weightless. The street outside the car was dark and empty on this swampy late-June night in 1980. The last of the neighborhood children had been called inside to clear the way for the hustlers who governed much of the greater Newark, New Jersey, area, and particularly this township of Orange, during the wilderness of the nocturnal hours.

As Frances had noted, St. Marys Hospital was indeed less than half a mile from 181 Chapman Street, where the Peace family lived. They were parked outside their home within two minutes. Chapman Street was about a hundred yards long, dead-ending on South Center Street to the west and Hickory to the east. These bookends actually protected the 100 block from most of the neighborhoods nightly commerce; dealers found the short stretch claustrophobic, and they were slightly wary of Frances, who never hesitated to march outside at any hour and tell them to get the hell out of her sight.

Jackie carried her son inside, past the rusty fence and weedy rectangle of lawn, up the five buckled stoop stairs, across the narrow porch, and through the open front door, where the ceiling fan made the air cooler. The street had been deserted, but the parlor and dining room were crowded with family. She had eight siblings, enough that she couldnt keep track of who was living in the house at any given time. Still dizzy from labor and first feedings, she didnt bother to count how many were there tonight as she reluctantly let the baby be passed around the living room, from her father, Horace, to her sisters Camilla and Carol to her brothers Dante and Garcia. Then her son was crying, and Jackie took him back and carried him to the room on the second floor where they could be alone, which was all she really wanted right now.

Swaddle that baby and hell stop the crying, her mother called as she ascended the stairs.

I told you Im not swaddling anything in this heat! Jackie called in response. And to Carl, who was something like an adopted younger brother, If you see Skeet out tonight, tell him to get back here. Skeet was Robs father.

She laid the boy naked in the center of the mattress with a towel spread beneath him, and she lay beside him at the edge of the single bed to let him feed. They fell asleep that way, with her hand pressed against his back, holding him against her. His cries woke her in the early morning, and she raised her head hoping that Skeet would be therehe had left the hospital room abruptly a few hours after the birth, saying he had some things to take care ofbut she and the baby remained the only warm bodies in the room.

A SIDE FROM A few failed attempts to strike out on her own, Jackie Peace had lived on Chapman Street in Orange, New Jersey, since 1960, when she was eleven. The house had first belonged to her uncle and had been left in her fathers name when that uncle died of lung cancer. Back then, the Peaces had been one of two black families on a block of middle-class European immigrants, mostly Italian, and their race hadnt bothered anyone. In that climate, people didnt think much about race, at least not outwardly. They thought about work. They thought about family. They thought about property. Men woke early and rode buses and car pools to the factory jobs that were the lifeblood of the greater Newark economy. Women stayed home and raised children. Neighbors, in silent and efficient understanding, kept an eye on the homes on either side of theirs, most of which were turn-of-the-century clapboards with peaked roofs set atop fourth-floor atticsattics packed with old photo albums and records and dishware, remnants of the passing down of property from generation to generation beginning in the early 1900s. The homes were narrow and close together, but inside they felt big enough, with high ceilings and wide portals between rooms and long backyards shaded by native willow oaks. Police made regular patrols and were known by name.