To those still on patrol

Copyright Geirr H Haarr 2015

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

Published and distributed in the United States of America and Canada by

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, Maryland 21402-5034

This edition is authorized for sale only in the United States of America, its territories and possessions and Canada.

First Naval Institute Press eBook edition published in 2016.

ISBN 978-1-59114-398-7 (eBook)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

The right of Geirr H Haarr to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Maps by Peter Wilkinson

Typeset and designed by JCS Publishing Services Ltd, www.jcs-publishing.co.uk Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

MANY PEOPLE HAVE CONTRIBUTED to this book, some from a lifetime of their own research, others with a small but important detail. Their contributions are highly appreciated.

Above all, the selfless help and support from David Goodey is gratefully acknowledged. Were it not for him, this project would have been shelved a long time ago. Erling Skjold, Erik Ettrup, Stewart Clewlow, David Roberts and Andrew Smith are also thanked sincerely. Without their help and constant support nothing would have been achieved.

The nameless staffs of The National Archives at Kew, the Bundesarchiv in Koblenz and Freiburg, the Imperial War Museum in London and Riksarkivet in Oslo deserve thanks for patience and professional dedication.

The members of the Traditiekamer Onderzeedienst in Den Helder, Holland, Jouke Spoelstra and Frans Klut, are warmly thanked for great enthusiasm and superb assistance, together with Hans Jehee of the Werkgroep Kriegsmarine and Anselm van der Peet of the Netherlands Institute for Naval History.

Likewise, Horst Bredow and Peter Monte at the U-boot Archiv in Cuxhaven are also thanked for sharing their time and keenness with me and for letting me use their files and archives. Sadly I received the news that Horst Bredow had passed away as the manuscript of this book was being completed. He spent a lifetime dedicated to naval history and he will be deeply missed.

I owe George Malcomson at the Royal Navy Submarine Museum in Gosport great thanks for repeated support and assistance as well as Andrew Jeffrey and David Kett at Dundee International Submarine Memorial.

Basil Abbott, manager at Diss Museum in Norfolk is warmly thanked for his enthusiastic assistance.

Julian Mannering at Seaforth Publishing deserves many thanks for believing in me and giving me the deadlines I needed. Without his support the project might never have seen completion. The fine maps were made by Peter Wilkinson who has a patience beyond comprehension with my many demands and changes. Similarly, Steve Williamson has been fantastic in completing the manuscript.

My friends in RMHF, istein Berge, Atle Skarsten, Odin Leirvag, Tor demotland, Erik Ettrup, Asbjrn Huseb and Hjalmar Sunde have been providing information, archive material and photos as well as historical and military rectifications.

Rick Harding, Reinhard Hoheisel-Huxmann, Olve Dybvig, Atle Wilmar, Paul Sedal, Ragnar Ulstein, Jac Baart, Robert Briggs, Andrzej Bartelski, Peter Kreutzer, Thorsten Reich, Tore Eggan and Ulf Larsstuvold all deserve acknowledgement.

Last, but not least, thanks to my beloved wife Gro, for accepting that my passion for her is shared with that for naval history, listening patiently when I needed to discuss some detail and skilfully distracting me when I needed to relax.

Geirr H Haarr

Sola, Stavanger, August 2015

There is no room for mistakes in submarines.

You are either alive or dead.

Vice-Admiral Max Horton

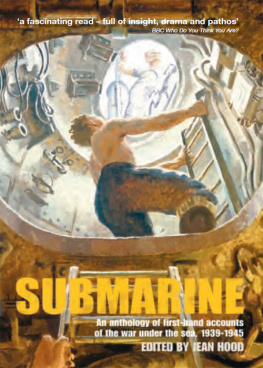

THE SUBMARINES OF THE late 1930s spent most of their time on the surface; they were really sea-going torpedo boats capable of operating underwater to hide from enemy predators. To be able to submerge, several fighting capabilities such as speed and observation had to be sacrificed, and going underwater was, early in WWII, largely a defensive or stealth measure. Its nature as a fighting vessel was very different from anything on the surface and required different thinking, training, tactics and strategies to function to its full potential; above all, the quality of the men and equipment, then as now, was what made a submarine work optimally.

In addition to the actual losses inflicted on enemy warships, transports and men, the threat of submarines in an area tied up vast resources dedicated to anti-submarine (A/S) measures. Inevitably, being a small vessel with relatively few men on board, each individual boat could be considered expendable by most naval strategists and could therefore be given riskier missions with less hope of coming back than other naval vessels. All the more so as it was a versatile weapon capable of delivering torpedoes and mines, performing reconnaissance and rescue missions, acting as a navigational beacon, and landing special units on enemy coastlines.

Above all, though, submarines were and are lethal threats to maritime supply lines and with Great Britain in particular being dependent on such, they were traditionally viewed with a certain distaste by the Royal Navy as well as the British public prior to WWII. The success of the German U-boats during the Great War did nothing to change this, even though British submarines were rather successful too, particularly in the Baltic and the Mediterranean. Quite to the contrary, the description of German U-boats and their submariners in British propaganda vastly overshadowed the exploits of the boats of the Royal Navy, which to some extent were toned down for political and intelligence reasons. In various disarmament conferences between the wars, British politicians actually sought to abolish the submarine as a weapon of war.

In early 1919 the Royal Navy could muster 122 submarines, 58 capital ships, 103 cruisers and 456 destroyers. Great Britain was the unchallenged master of the seas. Following WWI, widespread economic and social reforms were necessary and reduced military spending was inevitable. The British Navy would become almost insignificant within ten years and one by one, the shipbuilding and ordnance companies collapsed or merged, leaving a minimal workforce with relevant skills.

By September 1922, the number of submarines in commission with the Royal Navy had fallen to forty-four with eleven in reserve. A parallel plummeting of proficiency and understanding among the staffs in particular and naval officers in general, resulted in a British submarine policy that at best can be characterised as confused some years after WWI. Admiral Arthur Cheveson, C-in-C Far Eastern Fleet, inadvertently summed up the attitude of the Royal Navy in 1924 when he wrote in a memo: Until I have got a great number of destroyers on the station, I would not spend a shilling on submarines... submarine thinking officers, as well as others, are beginning to admit that their capabilities in their pet line are a good deal over-rated.