by Doris Lessing

It makes me laugh to read my diary. What a lot of contradictionsas though I were the unhappiest of women! But who could be happier? Could any marriage be more happy and harmonious than ours? When I am alone in my room I sometimes laugh for joy and cross myself and pray to God for many, many more years of happiness. I always write my diary when we quarrel

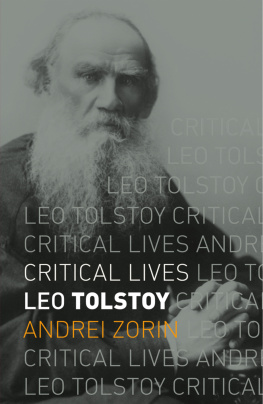

Sofia Tolstoy wrote the above in 1868, after six years of marriage. Many of her later diary entries also seem to have been written after quarrels.

This collection of Sofias diary entries is witness not only to her thoughts, but also to public events and to Lev Tolstoys workin the period covered by the collection, he wrote War and Peace, Anna Karenina and many other books. At the same time, we see the hard work of Sofia: she is an involved mother, though there are nursemaids and all kinds of help. She copies, and copies again, her husbands work.

why am I not happy? Is it my fault? I know all the reasons for my spiritual suffering: firstly it grieves me that my children are not as happy as I would wish. And then I am actually very lonely. My husband is not my friend: he has been my passionate lover at times, especially as he grows older, but all my life I have felt lonely with him. He doesnt go for walks with me, he prefers to ponder in solitude over his writing. He has never taken any interest in my children, for he finds this difficult and dull .

Sofia longs for new landscapes, intellectual development, art, contact with people: To each his fate. Mine was to be the auxiliary to my husband

When the Tolstoys were first married, they read each others diaries, as a part of their plan to preserve perfect intimacy between them, but later they might easily create two diaries, one for the other to read, one to remain private.

Sofia had thirteen children with Lev. Some of them died while still babiesone little boy in particular, Vanechka, who was adored by both parents. In War and Peace , Tolstoy writes painfully about the sufferings of parents who know how easily some small illness may snatch away their children.

Like most women at the time, Sofia was at the mercy of her reproductive systemthe advent of the pill was still almost a century away.

There is an interesting episode in Anna Karenina relating to this predicament of nineteenth-century women. Anna is in exile from society due to her adultery, so she is staying in the country. She is visited by Dolly, her sister-in-law. Anna tells Dolly about the birth-control methods of the time. Dolly reacts to the information not with delight, as Anna had expected, but with revulsionthe idea of women refusing to bear children, their traditional role in life, is simply unacceptable to her. On her way back from Anna, Dolly hears a peasant woman giving thanks to God, who has rescued her by taking one of her children, leaving more food for the rest. Dolly is sorry for the peasant, but not shocked. This episode illustrates womens views towards contraception at the timeAnna, the one person who accepts its use, is placed outside spheres of acceptable social behaviour, while Dolly, representing social norms, is shocked at the very idea; however, she is not shocked by the peasant womans more traditional means of birth control. In another episode in the novel, Dolly waits for a visit from her husband Stepan, which is likely to leave her pregnant, and even more worried about money than she already is. What a scamp, she muses about Stepan. In this, we see how accepted the burdens of childbirth were for women at the time.

Another factor in the Tolstoys marital circumstances which proved difficult for Sofiaas it emerges from her diarieswas Levs relationship with Vladimir Grigorevich Chertkov. Chertkov was Levs secretary. He became one of Levs closest friends and confidants, and the founder of Tolstoyanismthe school of thought of those who followed Tolstoys religious views. He was also a singularly unpleasant version of Lev himself. Lev became in thrall to Chertkov. Chertkov loathed Sofia, intriguing against her in every way he could.

Tolstoy once said that he had been more in love with men than he had ever been with women. The Kreutzer Sonata , which poor Sofia had to copy, though she hated it, seems to me a classic description of male homosexuality. There was a great scandal over this novel, which describes the murder of a supposed lover by the husband.

In defending this novel, which he did in another treatise, Tolstoy returned to his ways of describing real women as being like doves, pure and innocent. Had he ever met any real women? When it comes to the figure of Tolstoy himself, he is a sea of contradictions. He was an ideologue, he preached at people, he was always in the right, and yet he took his stand on a number of different and sometimes opposing platforms.

He was also a bad husband, inconsiderate sexually, and in other ways. For instance, he insisted on his poor wife breastfeeding the infants, though her nipples cracked and it was painful for her. She wanted to use wet nurses. The truth was, the great Tolstoy was a bit of a monster.

Sofia Tolstoy must have divided her later years into before Chertkov and after Chertkov. We have had plenty of opportunities to study the activities of ideologues, but Vladimir Chertkov was a newish phenomenon, and probably Sofias inability to cope with this man was partly because of the difficulty in categorizing him: was he religious?oh yes, dedicated to the good, a fanatic in fact. But Chertkov wanted just one thingto dominate Tolstoy, and in this he succeeded. And there was not only Chertkov, but all the fans who turned up from everywhere in the world, expecting to be housed, fed and advised by the Master. They turned servants out of their beds, slept in the corridors, were under everyones feet.

Sofia was not well: it was said then, and is still said now, that she was demented. I am not surprised if she was. Tolstoy was threatening to leave her, leave the family, which meant to be with Chertkov. Sofia rushed out, distraught, into a pond. They saved her. I want to leave the dreadful agony of this lifeI can see no hope, even if L.N. does at some point return

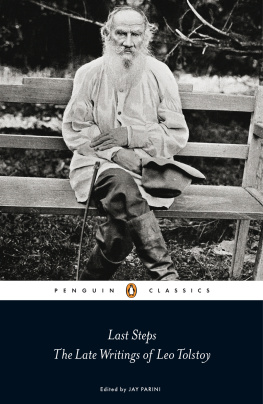

In the end the whole world watched as Tolstoy fled his home for the little house near the railway where he died. Sofia was forbidden to go to her dying husband by Chertkov until the very last moment.

Sofia Tolstoy lived for many long years as Tolstoys widow. She sometimes went to visit his grave, where she begged forgiveness from him for her failings.

The diary entries in these pages bear witness to a remarkable life: the life of an exceptional woman, married to one of the most exceptional men of the time, with all her passions and difficulties laid bare. This is a book which is interesting for what it says about the predicament of women in the past, and how that compares to their present circumstances. While reading it, I was so enthralled that I found myself dreaming about Sofia, about speaking to her myself, desperately wanting to reach out to her and offer her words of comfort for her pain. Perhaps, hopefully, this record of her struggles will be a comfort and inspiration to present and future generations.